Life (19 page)

* * *

T

he

R

onettes were

the hottest girl group in the world, and early in 1963 they’d just released one of the greatest songs ever recorded, “Be My Baby,” produced by Phil Spector. We toured with the Ronettes on our second UK tour, and I fell in love with Ronnie Bennett, who was the lead singer. She was twenty years old and she was extraordinary, to hear, to look at, to be with. I fell in love with her silently, and she fell in love with me. She was as shy as I was, so there wasn’t a lot of communication, but there sure was love. It all had to be kept very quiet because Phil Spector was and notoriously remained a man of prodigious jealousy. She had to be in her room all the time in case Phil called. And I think he quickly got a whiff that Ronnie and I were getting on, and he would call people and tell them to stop Ronnie seeing anybody after the show. Mick had cottoned to her sister Estelle, who was not so tightly chaperoned. They came from a huge family. Their mother, who had six sisters and seven brothers, lived in Spanish Harlem, and Ronnie had first stepped out onto the Apollo stage when she was fourteen years old. She told me later that Phil was acutely conscious of his receding hairline and couldn’t stand my abundant barnet (London rhyming slang for hair: Barnet Fair). This insecurity was so chronic that he would go to terrible lengths to allay his fears—to the point where, after he married Ronnie in 1968, he made her prisoner in his California mansion, barely allowing her out and preventing her from singing, recording or touring. In her book she describes Phil taking her to the basement and showing her a gold coffin with a glass top, warning her that this was where she would be on display if she strayed from his rigorous rules. Ronnie had a lot of guts at that young age, which didn’t, however, get her out of Phil’s grip. I remember watching Ronnie do a vocal at Gold Star Studios: “Shut up, Phil. I know how it should go!”

Ronnie remembered how we were on that tour together:

Ronnie Spector:

Keith and I made ways to be together—I remember on that tour, in England, there was so much fog that the bus had to actually stop. And Keith and I got out and we went over to this little cottage and this old lady came to the door, sort of heavy and so sweet—and I said, “Hi, I’m Ronnie of the Ronettes” and Keith said, “I’m Keith Richards of the Rolling Stones and we can’t move our bus because we can’t see any farther than our hands.…” So she says, “Oh! Come on in, kids, I’ll give you something!” and she gave us scones, tea and then she gave us extra ones to bring back to the bus and to be honest, those were the happiest days of my entire career.

We were twenty years old and we just fell in love. What do you do when you hear a record like “Be My Baby” and suddenly you are? But same old story, can’t let anybody else know. So it was a terrible thing in a way. But basically, it was just hormones. And sympathy. Without us even thinking about it, we both realized that we were awash in this sea of sudden success and that other people were directing us and we didn’t like it. But nothing much you can do about it. Not on the road. But then, we would never have met if we had not been in this weird situation. Ronnie only wanted the best for people. And never quite got the best for herself. But her heart was definitely in the right place. I went to the Strand Palace Hotel and looked her up early one morning. “Just want to say hello.” The tour was about to leave for Manchester or somewhere, we had to all get on the bus, so I just figured I’d pick her up before. Nothing happened then. I just helped her to pack. But it was a very bold move for me, because I’d never put the come-on to any chick. We were reunited in New York not long after this, as I will tell. And I’ve always kept in touch with Ronnie. On the day of 9/11 we were recording together, a song called “Love Affair,” in Connecticut. It is a work in progress.

I

n the arrogance of youth,

the idea of being a rock star or a pop star was taking a step down from being a bluesman and playing the clubs. For us to have to dip our feet into commercialism, in 1962 or ’63, was for a small while distasteful. The Rolling Stones, when they started, the limits of their ambition was just to be the best fucking band in London. We disdained the provinces; it was a real London mind-set. But once the world beckoned, it didn’t take long for the scales to fall from the eyes. Suddenly the whole world was opening up, the Beatles were proving that. It’s not that easy being famous; you don’t want to be. But at the same time you’ve got to be in order to do what you’re doing. And you realize you’ve already made the deal at the crossroads. Nobody said this was the deal. But within a few weeks, months, you realize that you’ve made the deal. And that you are now set on a path that is not your aesthetically ideal path. Stupid teenage idealisms, purisms, bullshit. You’re now set on the path, along with all those people that you wanted to follow anyway, like Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson. You’ve already made the fucking deal. And now you have to follow it, just like all your brothers and sisters and ancestors. You are now on the road.

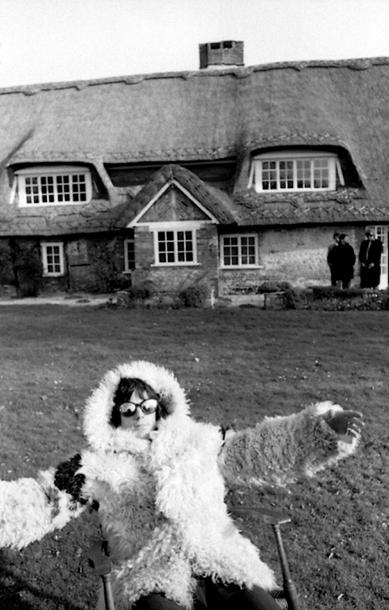

Michael Cooper / Raj Prem Collection

The Stones’ first tour of the USA. Meeting Bobby Keys at the San Antonio State Fair. Chess Records, Chicago. I hook up with the future Ronnie Spector and go to the Apollo in Harlem. Fleet Street (and Andrew Oldham) provide our new popular image: long-haired, obnoxious and dirty. Mick and I write a song we can give the Stones. We go to LA and record with Jack Nitzsche at RCA. I write “Satisfaction” in my sleep, and we have our first number one. Allen Klein becomes our manager. Linda Keith breaks my heart. I buy my country house, Redlands. Brian begins to melt down—and meets Anita Pallenberg.

T

he first time the Stones went to America, we felt we’d died and gone to heaven. It was the summer of ’64. Everybody had their own little thing about America. Charlie would go down to the Metropole when it was still swinging, and see Eddie Condon. The first thing I did was visit Colony Records and buy every Lenny Bruce album I could find. Yet I was amazed by how old-fashioned and European New York seemed—quite different to what I’d imagined. Bellboys and maître d’s, all that sort of thing. Unnecessary fluff and very unexpected. It was as if somebody had said, “These are the rules” in 1920 and it hadn’t changed a bit since. On the other hand, it was the fastest-moving modern place you could be.

And the radio! You couldn’t believe it after England. Being there at a time of a real musical explosion, sitting in a car with the radio on was beyond heaven. You could turn the channels and get ten country stations, five black stations, and if you were traveling the country and they faded out, you just turned the dial again and there was another great song. Black music was exploding. It was a powerhouse. At Motown they had a factory but without turning out automatons. We lived off Motown on the road, just waiting for the next Four Tops or the next Temptations. Motown was our food, on the road and off. Listening to car radios through a thousand miles to get to the next gig. That was the beauty of America. We used to dream of it before we got there.

I knew Lenny Bruce might not be every American’s sense of humor, but I thought from there I could get a thread to the secrets of the culture. He was my entrée into American satire. Lenny was the man.

The Sick Humor of Lenny Bruce;

I’d taken him in long before I got to America. So I was well prepared when on

The Ed Sullivan Show

Mick wasn’t allowed to sing “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” we had to sing “Let’s Spend Some Time Together.” Talk about shades and nuances. What does that mean, especially to CBS? A night is not allowed. Unbelievable. It used to make us laugh. It was pure Lenny Bruce—“Tittie” is a dirty word? What’s dirty? The word or the tittie?

Andrew and I walked into the Brill Building, the Tin Pan Alley of US song, to try and see the great Jerry Leiber, but Jerry Leiber wouldn’t see us. Someone recognized us and took us in and played us all these songs, and we walked out with “Down Home Girl,” by Leiber and Butler, a great funk song that we recorded in November 1964. Looking for the Decca offices in New York on one of our adventures, we ended up in a motel on 26th and 10th with a drunken Irishman called Walt McGuire, a crew cut guy who looked as if he’d just gotten out of the American navy. This was the head of the US Decca office. And we suddenly realized the great Decca record company was actually some warehouse in New York. It was a card trick. “Oh yes, we have big offices in New York.” And it was down on the docks on the West Side Highway.

We were listening to chick songs, doo-wop, uptown soul: the Marvelettes, the Crystals, the Chiffons, the Chantels, all of this stuff coming in our ears, and we’re loving it. And the Ronettes, the hottest girl group around. “Will You Love Me Tomorrow” by the Shirelles. Shirley Owens, their lead singer, had an almost untrained voice, beautifully balanced with a fragility and simplicity, almost as if she wasn’t a singer. All this stuff you heard—no doubt the Beatles had an effect—“Please Mr. Postman,” and “Twist and Shout” by the Isley Brothers. If we’d tried to play anything like that down at the Richmond Station Hotel it would have been “

What?

They’ve gone mad.” Because they wanted to hear hard-duty Chicago blues that no other band could play as well as we could. The Beatles certainly could never have played it like that. At Richmond it was our workmanlike duty not to stray from the path.

The first show we ever did in America was at the Swing Auditorium in San Bernardino, California. Bobby Goldsboro, who taught me the Jimmy Reed lick, was on the show, and the Chiffons. But earlier we’d had the experience of Dean Martin introducing us at the taping of the

Hollywood Palace

TV show. In America then, if you had long hair, you were a faggot as well as a freak. They would shout across the street, “Hey, fairies!” Dean Martin introduced as something like “these long-haired wonders from England, the Rolling Stones.… They’re backstage picking the fleas off each other.” A lot of sarcasm and eyeball rolling. Then he said, “Don’t leave me alone with

this,

” gesturing with horror in our direction. This was Dino, the rebel Rat Packer who cocked his finger at the entertainment world by pretending to be drunk all the time. We were, in fact, quite stunned. English comperes and showbiz types may have been hostile, but they didn’t treat you like some dumb circus act. Before we’d gone on, he’d had the bouffanted King Sisters and performing elephants, standing on their hind legs. I love old Dino. He was a pretty funny bloke, even though he wasn’t ready for the changing of the guard.

On to Texas and more freak show appearances, in one case with a pool of performing seals between us and the audience at the San Antonio Texas State Fair. That was where I first met Bobby Keys, the great saxophone player, my closest pal (we were born within hours of each other). A soul of rock and roll, a solid man, also a depraved maniac. The other guy on that gig was George Jones. They trailed in with tumbleweed following them, as if tumbleweed was their pet. Dust all over the place, a bunch of cowboys. But when George got up, we went whoa, there’s a master up there.

You have to ask Bobby Keys how big Texas is. It took me thirty years to convince him that Texas was actually just a huge landgrab by Sam Houston and Stephen Austin. “No fucking way. How dare you!” He’s red in the face. So I laid a few books on him about what actually happened between Texas and Mexico, and six months later he says, “Your case seems to have some substance.” I know the feeling, Bob. I used to believe that Scotland Yard was lily-white.

But Bobby Keys should be allowed to tell the tale of our first meeting, since this is a Texan story. He flatters me, but in this case I have allowed it.

Bobby Keys

: I first met Keith Richards physically in San Antonio, Texas. I was so biased against that man before I actually met him. They recorded a song, “Not Fade Away,” by a guy named Buddy Holly, born in Lubbock, Texas, same as me. I said, “Hey, that was Buddy’s song. Who are these pasty-faced, funny-talking, skinny-legged guys to come over here and cash in on Buddy’s song? I’ll kick their asses!” I didn’t care much for the Beatles. I kind of secretly liked them, but I saw the death of the saxophone unraveling before my eyes. None of these guys have saxes in their bands, man! I’m going to be playing Tijuana Brass shit for the rest of my life. I didn’t think, “Great, we’re going to be on the same show.” I was playing with a guy named Bobby Vee, who had a hit at the time called “Rubber Ball” (“I keep bouncing back to you”), and we were headlining the show until They came on, and then they were headlining the show. And this was Texas, man. This was my stomping ground.

We were all staying at the same hotel in San Antonio, and they were out on the balcony, Brian and Keith, and I think Mick. I went out and listened to them, and there was some actual rock and roll going on there, in my humble opinion. And of course I knew all about it, given it was invented in Texas and me being present at its birth. And the band was really, really good, and they did “Not Fade Away” actually better than Buddy ever did it. I never said that to them or anybody else. I thought maybe I had judged these guys too harshly. So the next day we must have played three shows with them, and about the third time I was in the dressing room with them, they were all talking about the American acts, how before they went on stage they all changed clothes. Which we did. We went on with our black mohair suits and white shirts and ties, which was stupid, because it was nine hundred degrees outside, summertime in San Antonio. They were saying, “Why don’t we ever change clothes?” And they said, “Yeah, that’s a good idea.” I’m expecting them to whip out some suits and ties, but they just changed clothes with each other. I thought that was great.

You got to realize that the vision, the image, according to 1964 US rock-and-roll standards, was mohair suit and tie, and nicey-nicey, ol’ boy next door. And all of a sudden here comes this truckload of English jackflies, interlopers, singing a Buddy Holly song! Damn! I couldn’t really hear all that well, amplifiers and PAs being what they were, but man, I felt it. I just fucking felt it, and it made me smile and dance. They didn’t dress alike, they didn’t do sets, they just broke all the fucking rules and made it work, and that is what enchanted the shit out of me. So, being inspired by this, the next day I’d got my mohair suit out and put the trousers on, and my toenails split the seam down the front, and I didn’t have anything else to wear. So I wore my shirt and tie and put on Bermuda shorts and cowboy boots. I didn’t get fired. I got “What are you… How dare… What is fucking going on, man?” It redefined a lot of stuff for me. The American music scene, the whole set of teenage idols and clean-cut boys from next door and nice little songs, all that went right out the fucking window when these guys showed up! Along with the press, “Would you let your daughter,” all that stuff, forbidden fruit.

Anyway, somehow they noticed what I did, and I noticed what they did, and we just kind of met there, really just brushed paths. And then I ran into them again in LA when they were doing the T.A.M.I. show. I discovered that Keith and I had the same birthday, both born 12/18/43. He told me, “Bobby, you know what that means? We’re half man and half horse, and we got a license to shit in the streets.” Well, that’s just one of the greatest pieces of information I’d ever received in my life!

The whole heart and soul of this band is Keith and Charlie. I mean, that’s apparent to anybody who’s breathing, or has a musical bone in his body. That is where the engine room is. I’m not a schooled musician, I can’t read music, I never had any professional training. But I can feel stuff, and when I heard him playing guitar, it reminded me so much of the energy I heard from Buddy and I heard from Elvis. There was something there that was the real deal, even though he was playing Chuck Berry. It was still the real deal, you know? And I’d heard some pretty good guitar players coming out of Lubbock. Orbison came from Vernon, a few hours away, I used to listen to him, and Buddy at the skating rink, and Scotty Moore and Elvis Presley would come through town, so I’d heard some pretty good guitar players. And there was just something about Keith that immediately reminded me of Holly. They’re about the same size; Buddy was a skinny guy, had bad teeth. Keith was a mess. But some folks, they just got a look in their eye, and he looked dangerous, and that’s the truth.

There was the stark thing you discovered about America—it was civilized round the edges, but fifty miles inland from any major American city, whether it was New York, Chicago, LA or Washington, you really did go into another world. In Nebraska and places like that we got used to them saying, “Hello, girls.” We just ignored it. At the same time they felt threatened by us, because their wives were looking at us and going, “That’s interesting.” Not what they were used to every bloody day, not some beer-swilling redneck. Everything they said was offensive, but the actual drive behind it was very much defense. We just wanted to go in and have a pancake or a cup of coffee with some ham and eggs, but we had to be prepared to put up with some taunting. All we were doing was playing music, but what we realized was we were going through some very interesting social dilemmas and clashes. And whole loads of insecurities, it seemed to me. Americans were supposed to be brash and self-confident. Bullshit. That was just a front. Especially the men, especially in those days, they didn’t know quite what was happening. Things did happen fast. I’m not surprised that a few guys just couldn’t get the spin on it.

The only hostility I can recall on a consistent basis was from white people. Black brothers and musicians at the very least thought we were interestingly quirky. We could talk. It was far more difficult to break through to white people. You always got the impression that you were definitely a threat. And all you’d done was ask, “Can I use your bathroom?” “Are you a boy or a girl?” What are you gonna do? Pull your cock out?

Back in England we had a number one album, but out in the middle of America nobody knew who we were. They were more aware of the Dave Clark Five and the Swinging Blue Jeans. In some towns we got some real hostility, real killer looks in our direction. Sometimes we got the sense that an exemplary lesson was about to be taught us, right then and there. We’d have to make a quick getaway in our faithful station wagon with Bob Bonis, our road manager, great guy. He’d been on the road with midgets, performing monkeys, with some of the best acts of all time. He eased us into America, driving five hundred miles a day.