Life (65 page)

Mick put a vocal on the song, but he couldn’t feel it, he couldn’t get it, and the track sounded terrible. Rob couldn’t mix it with this vocal, so we tried to fix it one night with Blondie and Bernard, barely able to stand from fatigue, snatching sleep in turns. We came back and found the tape had been sabotaged in the meantime. All kinds of skulduggery went on. Eventually Rob and I had to steal the two-inch master tapes of the half mixes of “Thief in the Night” from Ocean Way studios in LA, where we’d recorded it, and fly them to the East Coast, where I had now returned homewards to Connecticut. Pierre found a studio on the north shore of Long Island where we remixed it to my liking for two days and two nights, with my vocal. Sometime during one of those nights Bill Burroughs died, so in homage to his work I sent angry Burroughsian cut-ups to Don Was, the producer in the middle—you rat, this is going to be finished my way, nobody else’s way, with screaming headline cuttings and headless torsos. Batten down the hatches; we’re going to war. I just had a beef with Don. I love the man and we got over it right away, but I was sending him terrible messages. When you’re coming to the end of a record, anybody who gets in the way of what you want to do is the Antichrist. This was near to the deadline, so the quickest way to get the tapes back to LA was to take them by speedboat from Port Jefferson, Long Island, to Westport, the nearest harbor to my house on the Connecticut coast. We did this at midnight, under a very nice moon, roaring across the Long Island Sound, successfully avoiding the lobster pots with a swerve here and a shout there. Next day Rob got them to New York and they were flown back to LA to the mastering studio to be inserted into the album.

Exceptionally for a Stones song, Pierre de Beauport got a writing credit on the track, along with me and Mick.

The big problem now was that it was looking as if I was going to be singing three songs on the album, which was unheard-of. And to Mick unacceptable.

Don Was:

I firmly believed in Keith’s right to have a third vocal on the record, but Mick was having none of it. I’m sure Keith is totally unaware of all that it took to get “Thief in the Night” on that record. Because it was a total standoff between these two guys, neither one was backing down, and we were going to miss the release date and the tour was going to start without a new album out there. And the night before the deadline, I had a dream, and I called Mick up and I said, I know your point about him singing three songs, but if two were at the end of the record and they were together as a medley, if there wasn’t a lot of space between the two songs, then they would be seen as one big Keith thing at the end of the record. And for the people you’re concerned about, who don’t love Keith songs, they could just stop after your last vocal, and for those people who love Keith stuff, it would be one last Keith, so view it not as a third song, but as a medley, and we’ll leave a space before it begins, and we’ll leave very little space between the two songs. And he went with that. And I’m sure Keith has no idea, or Jane, no one knows what happened. So that gave Mick an out, basically, because it was a standoff. And so those two became one song. However, the song that it got paired up with is “How Can I Stop,” which is one of the best Rolling Stones songs ever.

It’s amazing… Keith absolutely at his best, and Wayne Shorter, what an odd pairing, to have Wayne Shorter just blowing, it turns into Coltrane at the end, it turns into “A Love Supreme” at the end. There was something about it. There were like ten people playing at once, and it was a magical session. There were no overdubs to that thing; it just came out like that. And the other thing was, that night, when we cut it, Charlie was leaving, it was the end, it was the last track we cut for that album. They were tearing down the instruments the next day. And Charlie had a car waiting out in the alley. And so he does this big flourish at the end, that’s the last take, and it’s like a grand hurrah, and the way everyone was feeling at the end of that record, I didn’t think they’d ever make another. And so I saw “How Can I Stop” as the coda. I thought it was the last thing they were ever going to cut, and what a great way to end it. How can I stop once I’ve started? Well, you just stop.

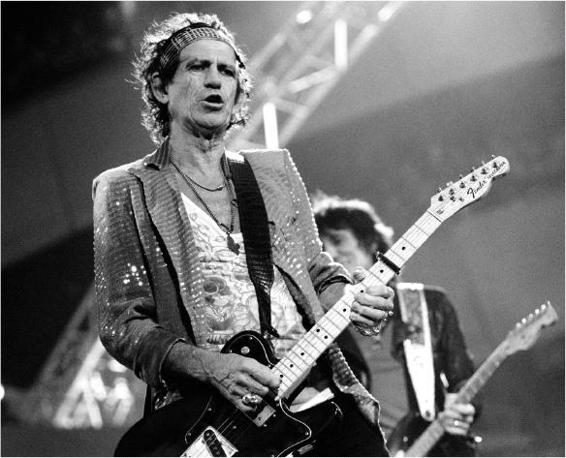

Peter Pakvis / Getty Images

Recording the Wingless Angels in Jamaica. We set up a studio in my home in Connecticut, and I break some ribs in my library. A recipe for bangers and mash. A hungover safari in Africa. Jagger’s knighthood; we work and write together again. Paul McCartney comes down the beach. I fall from a branch and hit my head. A brain operation in New Zealand.

Pirates of the Caribbean,

my father’s ashes, and Doris’s last review.

T

wenty-odd years after I began playing with local Rastafarian musicians, I went back to Jamaica with Patti for Thanksgiving 1995. I’d invited Rob Fraboni and his wife to come and stay with us—Rob had originally met this crew in 1973, when I first knew them. Fraboni’s holiday was canceled on day one because it turned out that at this moment all the surviving members were present and available, which was rare; there had been a lot of casualties and ups and downs and busts, but this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to record them. Fraboni somehow had bits of recording equipment available courtesy of the Jamaican minister of culture and promptly offered to record the setup. That was a gift from the gods!

A gift because Rob Fraboni is a genius when you want to record things outside the usual frame. His knowledge and his ability to record in the most unusual places are breathtaking. He worked as a producer on

The Last Waltz;

he remastered all the Bob Marley stuff. He’s one of the best sound engineers you can ever meet. He lives round the corner from me in Connecticut, and we’ve done a lot of recording together in my studio there, of which I’ll write more. Like all geniuses, he can be a pain in the arse, but it goes with the badge.

I christened the group the Wingless Angels that year from a doodle I made—which is on the album cover—of a figure like a flying Rasta, which I’d left lying around. Somebody asked me what’s that, and just off the top of my head I said, that’s a wingless angel. There was one new addition to this group, in the person of Maureen Fremantle, a very strong voice and the rare presence in Rasta lore of a female singer. This is how we came together, as she tells it.

Maureen Fremantle:

One night Keith was with Locksie in Mango Tree bar in Steer Town, and I was passing that night, so Locksie says, sister Maureen, come in, come and have a drink. And I go in and I meet this guy. Keith hug me and says, this sister look like a real sister. And then we started to have a drink; I was having rum and milk. And then it was like… I don’t know, the power of Jah. I just start to sing. Yes, just start to sing. And Keith said, this lady have to come by me. And it never turned back from then. I just start to sing. And I was reeling. And I started to sing, love, peace, joy, happiness, and it burst into one thing. It was something else.

Fraboni had a microphone in the garden, and at the beginning of the recording you hear the crickets and frogs, the ocean beyond the veranda. There are no windows in the house, just wooden shutters. You can hear people playing dominoes in the back. It has a very powerful feel, and feel is everything. We took the tapes back to the US and began to figure how to keep the intrinsic core. That’s when I met Blondie Chaplin, who came along to the sessions with George Recile, who became Bob Dylan’s drummer. George is from New Orleans, and there are many different races in there—he’s Italian, black, Creole, the whole lot. What’s startling is the blue eyes. Because with those blue eyes, he can get away with anything, including crossing the tracks.

I wanted to bring the Angels into a more global mood, and guys from everywhere began to show up at the Connecticut overdubbing sessions. The incredible fiddler Frankie Gavin, who founded De Dannan, the Irish folk group, came in with his great Irish humor, and a certain feel began to emerge. This was obviously not a record of great commercial appeal, but it had to be done, and I’m still very proud of it. So much so that there was another on the way as I was writing this.

V

ery soon after

E

xile,

so much technology came in that even the smartest engineer in the world didn’t know what was really going on. How come I could get a great drum sound back in Denmark Street with one microphone, and now with fifteen microphones I get a drum sound that’s like someone shitting on a tin roof? Everybody got carried away with technology and slowly they’re swimming back. In classical music, they’re rerecording everything they rerecorded digitally in the ’80s and ’90s because it just doesn’t come up to scratch. I always felt that I was actually fighting technology, that it was no help at all. And that’s why it would take so long to do things. Fraboni has been through all of that, that notion that if you didn’t have fifteen microphones on a drum kit, you didn’t know what you were doing. Then the bass player would be battened off, so they were all in their little pigeonholes and cubicles. And you’re playing this enormous room and not using any of it. This idea of separation is the total antithesis of rock and roll, which is a bunch of guys in a room making a sound and just capturing it. It’s the sound they make together, not separated. This mythical bullshit about stereo and high tech and Dolby, it’s just totally against the whole grain of what music should be.

Nobody had the balls to dismantle it. And I started to think, what was it that turned me on to doing this? It was these guys that made records in one room with three microphones. They weren’t recording every little snitch of the drums or the bass. They were recording the room. You can’t get these indefinable things by stripping it apart. The enthusiasm, the spirit, the soul, whatever you want to call it, where’s the microphone for that? The records could have been a lot better in the ’80s if we’d cottoned on to that earlier and not been led by the nose by technology.

In Connecticut, Rob Fraboni created a studio, my “Room Called L”—because it was L-shaped—in the basement of my house. I had a year off during 2000 and 2001, and I worked with Fraboni to build it up. We put a microphone facing the wall, not pointed at an instrument or an amplifier. We tried to record what was coming off of the ceiling and off of the walls rather than dissecting every instrument. You don’t, in fact, need a studio, you need a room. It’s just where to put the microphones. We got a great eight-track recorder made by Stephens, which is one of the smoothest, most incredible recording machines in the world, and it looks like the monolith in Kubrick’s 2001.

The only track I’ve put out from “L” so far is “You Win Again,” on the Hank Williams tribute album

Timeless,

which got a Grammy. Lou Pallo, who was Les Paul’s second guitar player for years, maybe centuries, played guitar on it. Lou was known as “the man of a million chords.” Incredible guitar player. He lives in New Jersey. “What’s your address, Lou?” “Moneymaker Road,” he says. “It doesn’t live up to its name.” George Recile played drums. We had the makings of a house band, and anyone that was around could come and play. Hubert Sumlin would come by, Howlin’ Wolf’s guitar player, of whose music Fraboni later made a very good record called

About Them Shoes.

Great title. On September 11, 2001, we were cut short in the middle of recording with my old flame Ronnie Spector, a song called “Love Affair.”

You can get into a bubble if you just work with the Stones. Even with the Winos it can happen. I find it very important to work outside of those areas. It was inspiring to work with Norah Jones, with Jack White, with Toots Hibbert—he and I have done two or three versions of “Pressure Drop” together. If you don’t play with other people, you can get trapped in your own cage. And then, if you’re sitting still on the perch, you might get blown away.

Tom Waits was an early collaborator back in the mid-’80s. I didn’t realize until later that he’d never written with anyone else before except his wife, Kathleen. He’s a one-off lovely guy and one of the most original writers. In the back of my mind I always thought it would be really interesting to work with him. Let’s start with a bit of flattery from Tom Waits. It’s a beautiful review.

Tom Waits:

We were doing

Rain Dogs.

I was living in New York at the time, and someone asked if there was anybody I wanted to play on the record. And I said, how about Keith Richards? I was just kidding around. It was like saying Count Basie or Duke Ellington, you know? I was on Island Records at the time, and Chris Blackwell knew Keith from Jamaica. So somebody got on the phone, and I said no, no, no! But it was too late. Sure enough, we got a message: “The wait is over. Let’s do it.” So he came to RCA, a huge studio with high ceilings, with Alan Rogan, who was his guitar valet, and about 150 guitars.

Everybody loves music. What you really want is for music to love you. And that’s the way I saw it was with Keith. It takes a certain amount of respect for the process. You’re not writing it, it’s writing you. You’re its flute or its trumpet; you’re its strings. That’s real obvious around Keith. He’s like a frying pan made from one piece of metal. He can heat it up really high and it won’t crack, it just changes color.

You have your own preconceived ideas about people that you already know from their records, but the real experience, ideally, hopefully, is better. That certainly was the case with Keith. We kind of circled each other like a couple of hyenas, looked at the ground, laughed and then we just put something on, put some water in the swimming pool. He has impeccable instincts, like a predator. He played on three songs on that record: “Union Square,” we sang on “Blind Love” together, and on “Big Black Mariah” he played a great rhythm part. It really lifted the record up for me. I didn’t care how it sold at all. As far as I was concerned it had already sold.

Then a few years later we hooked up in California. We got together every day at this little place called Brown Sound, one of those funky old rehearsal places with no windows and carpet on the wall, smells like diesel. We started writing. You have to get relaxed enough around someone to be able to throw out any kind of twisted idea that might test your mind, that comfort zone. I remember on my way to the studio, I taped a Sunday gospel brunch Baptist preacher coming right out of the radio. And the title of the sermon was “The Carpenter’s Tools”! It was all about the carpenter’s tools, how he went into his bag and pulled out all these tools.… We laughed about that for a long time. And then Keith played me a copy he had of “Jesus Loves Me,” sung by Aaron Neville, something he’d sung in a rehearsal, just a cappella. So he likes diamonds in the rough, he likes Zulu music, Pygmy music, the arcane, obscure and impossible to categorize music. We wrote a whole bunch of songs, one was called “Motel Girl” and another was “Good Dogwood.” And that’s where we wrote “That Feel”—I put that on

Bone Machine

.

One of my favorite things that he did is

Wingless Angels

. That completely slayed me. Because the first thing you hear is the crickets, and you realize you’re outside. And his contribution to capturing the sounds on that record just feels a lot like Keith. Maybe more like Keith than I had contact with when we got together. He’s like a common laborer in a lot of ways. He’s like a swabby. Like a sailor. I found some things they say about music that seemed to apply to Keith. You know, in the old days they said that the sound of the guitar could cure gout and epilepsy, sciatica and migraines. I think that nowadays there seems to be a deficit of wonder. And Keith seems to still wonder about this stuff. He will stop and hold his guitar up and just stare at it for a while. Just be rather mystified by it. Like all the great things in the world, women and religion and the sky… you wonder about it, and you don’t stop wondering about it.

In 1980, Bobby Keys, Patti, Jane and I paid a visit to the remaining Crickets in Nashville. Must have been something special, because we hired a Learjet to get there. We went to see Jerry Allison, alias Jivin’ Ivan, the Crickets’ drummer, the one who actually married Peggy Sue (though it didn’t last long), at his place he calls White Trash Ranch just outside of Nashville in Dickson, Tennessee. There was Joe B. Mauldin, bass player with Buddy. Don Everly was around on that trip, and to play

with

him, sitting around… these were the cats I was listening to on the goddamn radio twenty years ago. Their work had always fascinated me, and just to be in their house was an honor.

There was another wonderful expedition to record a duet with George Jones at the Bradley Barn sessions, “Say It’s Not You,” a song that Gram Parsons had turned me on to

.

George was a great guy to work with, especially when he had the hairdo going. Incredible singer. There’s a quote from Frank Sinatra, who says, “Second-best singer in this country is George Jones

.

” Who’s the first, Frank? We were waiting and waiting for George, for a couple of hours, I think. By then I’m behind the bar making drinks, not remembering that George is supposed to be on the wagon and not knowing why he was so late. I’ve been late many times and so no big deal. And when he turns up, the pompadour hairdo is perfect. It’s such a fascinating thing. You can’t take your eyes off it. And in a fifty-mile-an-hour wind it would still have been perfect. I found out later that he’d been driving around because he was a bit nervous about working with me. He’d been doing some reading up and was uncertain of meeting me.