Life: An Exploded Diagram (30 page)

Read Life: An Exploded Diagram Online

Authors: Mal Peet

Tags: #Young Adult, #Historical, #Adult, #Romance, #War

“Frankie . . .”

“I’m going to re-create Franklins, Clem. I’m going to plant pines up there. I’m going to rebuild the barn.”

I took hold of the phone again. I sat down.

“What?”

I sort of gurgled the word, I think.

“You heard me.”

“Frankie . . .”

“What? You think I’m crazy?”

“No. No, I . . . But, you know. You’re talking about turning the clock back, Frankie. I don’t think it’s possible.”

“Yes, it is. I’m very rich, and it’s what I want.”

“Yeah, okay, but . . .”

“Listen, Clem. Since I’ve been back here, in between poking pulp into my father’s mouth and wiping it off his chin, I’ve been working. Doing research. Looking at old maps. Old photographs, old prints. Talking to old people. Trouble is, there are fewer old people than there used to be. We are the old people now.”

And here I got a first glimmer of what she wanted. I blinked it away, though.

She said, “I’ve got a picture, a model, in my head of how the estate used to be in my grandfather’s time. When I was a girl. What I haven’t got is someone to share it with. Someone who remembers it the way I do and who cares as much as I do. Someone who’s as sentimental as I am.”

I was not, absolutely not, going to rise to that.

“Look, Frankie — it’s incredible, wonderful, to talk to you. To hear your voice again. And I feel terrible saying this, but it so happens I’ve got a meeting in half an hour. It’s important, and I’m going to be late.”

“I’m sorry. I won’t keep you. But will you think about it?”

“Think about what?”

“About coming home, Clem. About helping me remember. Being my artist again.”

I was stunned. That’s a cliché, I know. You can only be stunned if you’ve been whacked aside the head. I was stunned.

“You can’t be serious,” I managed to say. “You don’t know what you’re . . .”

“Yes, I do know what I’m asking. What I’m

not

asking is that you give up your brilliant career or anything. You could do your own work while you’re helping me. The Garden Cottage is vacant, and we could make you a beautiful studio in one of the courtyard buildings. All rent free, naturally.”

“Frankie, for Christ’s sake, it’s not the money.”

“No. It’s the love.”

I said, “Pardon me?”

“A code word for anything truly valuable. A child’s life, for example. Or the place you belong.”

“Frankie, please. I left a long time ago. And I never belonged there.”

“We’d be a great team. Three good eyes between us. Three ears. Two good legs. Nothing could stand in our way.”

I tried to laugh.

“I’m strong, Clem, but I’m lonely.”

“Please, Frankie. Don’t. I have to go. Look, I’ll ring you back.”

“Will you? Do you promise?”

“Yes,” I said. “I promise. Later today or tomorrow. What’s your number?”

I wrote it down.

“It used to be Bratton Morley 239,” I said, sort of absently, while I was writing.

“Fancy you remembering that,” Frankie said.

There was an

aha!

in her voice, as if she’d caught me out.

“So, okay,” I said.

“Go,” she said. “But think about it, Clem. Think about it very seriously. Think with your heart as well as your head.”

“Yeah, sure. I’ll do that. Bye, Frankie.”

“And Clem? Losing you hurt a lot more than losing my eye.”

She hung up before I did.

I sat in the crowded, southward-racketing subway car with the awkward portfolio of drawings between my knees. I was angry more than anything else. After a lifetime — a lifetime of hurt, of wondering, of remembering, of erasure — she’d chosen

this

morning, of all mornings, to reach out of the past and mess with my head.

Damn

her!

I hate being late. Punctuality is one of my obsessions. I looked at my watch again. No way was I going to make it to Val Leibnitz’s office by a quarter to nine.

I tried to focus on

Fantastic Machines,

on my pitch to the skeptical accountants.

It had taken me a long time to master the American art of boundless enthusiasm. That innocent, volcanic bubbling about almost anything. It went against my grain. During my early years in New York, I’d lost a number of jobs by being understated, apologetic, ironic. British, in short. It was Val Leibnitz who’d taken me to lunch one day and laid down the law, revealed the commandment:

Thou shalt believe absolutely in whatever shit you’re selling. Because if you don’t, why the hell would anybody who’s buying?

Obvious, of course. All the same, I couldn’t quite do it. It didn’t come naturally.

Then I read an interview with some actor, can’t remember who, who said, “It’s bull, that stuff about finding the character within yourself, identifying with his motivation, all of that. What you do is decide what kind of clothes he wears, what he likes to eat. Then what you do is put those clothes on, eat what he eats. Walk the way he walks, all of that. Sooner or later you start to talk like him. And that’s it. Acting isn’t a matter of truth or honesty. It’s a matter of impersonation.”

It was my Road to Damascus moment, that article. A revelation. I couldn’t do the foamy, heartfelt, swept-away-on-a-tsunami-of-conviction stuff. But someone who looked like me, behaved like me, dressed like me, had the same name as me, could. So I sat in the subway car, trying to become him, my impersonator. Checking that the cuffs of my stonewashed blue denim shirt came an inch below the cuffs of the sleeves of my gray Paul Smith jacket, that my black Peter Werth pants were free of lint, that there were no greasy streaks on my pale buckskin Timberland shoes. Looking sharp is important if, like me, you have the kind of face that can distress people.

“Come home,”

she’d said.

Home!

Hadn’t she realized what an insane idea, what a ridiculous term that was? It had been years and years, a whole lifetime, since I’d thought of Norfolk as my home. Or anywhere else, for that matter. And I was glad of it.

Home,

for me, is a word with stifling, subterranean connotations: badgery burrows, premature burials, walls that edge closer when you’re not looking. Norfolk had squeezed me, exploded me, had fired me into the world like the shell from a gun. Did Frankie really think that I would, or could, reverse that trajectory and worm back into the dark breech called

home

? Absurd.

And her, her . . . project, was, well, deeply eccentric. Or actually mad. Time simply will not be turned backward. Things cannot be what they were. We can’t have our childhoods back, re-create those worlds. And even if she

could,

she’d never live to see it. Those pines at Franklins had been at least a hundred years old.

Sane people do not refuse to grow up.

I wondered if perhaps she was, in fact, crazy. Rich people often are.

I wondered what she might be worth. Several millions, presumably.

“I’m going to rebuild the barn.”

“Be my artist again.”

I squirmed in my seat, remembering my clumsy efforts at drawing her. The heavy-handed way I’d scribbled and scratched at her litheness, her lightness. If only I’d been as good then as I am now. Now I’d be able to do her body justice.

Get a

grip,

Ackroyd, I told myself.

Fantastic Machines from Fantastic Movies.

Focus!

Over the years I had, naturally, tried to imagine an older Frankie. To imagine her as ravaged by time as I was. I’d done it to bury her ghost. To banish her. I’d packed weight onto her hips and belly. Turned her hair gray. Thickened her ankles. Pulled support stockings onto her legs. Now, to complete this grotesquery, I could add a glass eye and a limp. Maybe a walking stick. Yes.

But it wouldn’t do. It wouldn’t take.

Instead, she swung her hair away, descending to a kiss.

Biting her lip, bare-breasted, kneeling over me.

Pulling me down, sand on her fingers, the sea heaping itself onto the beach with a sound like

yes, yes.

She would stay young, sixteen, for ever. Unless I went back.

So I would call her, and say no. Yes, I would call her. Later, or maybe tomorrow.

“I’m strong, Clem, but I’m lonely.”

At least I hadn’t said, “So am I.”

The train whined to a halt. The doors opened. I’d lost track of where we were. It didn’t matter; the WTC, my stop, was the terminus. Peering through the press of bodies, I saw that we were at Chambers Street. Then the throb of the motor died. A tinny voice said something I couldn’t make out. PA announcements — at airports, railway stations, sports events — are among the things beyond the limits of my hearing. But the other passengers responded with the resigned truculence that New Yorkers specialize in and started to leave the train. Clearly, we were going no farther. I got to my feet.

Mass indecision took place. A great many people stood on the platform, thinking that there was a good chance that the problem would be fixed. Others headed up and out to the street.

It was eight forty-three. Damn! Val’s office was, what, four, five blocks away? Ten, twelve minutes at a fast limp. There goes your credibility, Ackroyd, I thought, climbing the stairs. Late for a crucial meeting. What does that say about your commitment? And where the hell is my enthusiastic impersonator? Thank you, Frankie, for coming uninvited out of the bloody past and making me late.

I turned onto West Broadway and called Val on my cell.

“Val? Hi, it’s me. Look, I’m sorry, really. I’m gonna be just a tiny bit late.”

“Clem, hi. So where are you?”

“Chambers and West. Don’t worry. I’ve got the work, and it’s good. But I had a call from home, you know? And I had to take it. Then the damn subway . . .”

Val said something I didn’t catch because a loud plane came overhead. I remember thinking it was unusual; planes don’t come in low over Lower Manhattan as a rule.

I stopped walking. I looked up at where Val’s office was, maybe thinking, stupidly, that she might be looking back at me from her window on floor 102 of the North Tower of the World Trade Center.

“Sorry, Val, I missed that.”

“I said, don’t sweat it. Right now we’re just going through some figures here.”

Something silvery, a fleck, like a fault in the clear blue sky, appeared then disappeared behind the twin towers.

I said, “Sounds like fun. I’ll —”

I pulled the phone away from my ear because it tried to savage me. A noise came out of it like . . . I still can’t say what it was like. Immensely brutal; the war cry of some huge primeval beast concentrated into a single second. Then silence.

And as I watched, the North Tower split open and extruded an impossibly vast orange-and-black flower of boiling flame and smoke, which, as it blossomed, spat out seeds of fire and steel and stone.

When the sound of it rolled down over us, we in the streets, the Spared, the Elect, began to shout obscenities and the various names of God.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Clem Ackroyd is an unreliable historian. In concocting his narrative of the Cuban Missile Crisis, he has used (and sometimes abused) material from the following books:

The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis,

edited by Ernest R. May and Philip D. Zelikow

One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War,

by Michael Dobbs

Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis,

by Robert F. Kennedy

The Cuban Missile Crisis: A Concise History,

by Don Munton and David A. Welch.

There is some evidence that he has also accessed the websites of the National Security Archive and the Cold War International History Project.

Finally: there are still approximately seven thousand nuclear warheads in existence. More than enough to blast the planet into a perpetual winter. I assume there are people who know where they all are. But we don’t talk about them much anymore. We have other things on our minds.

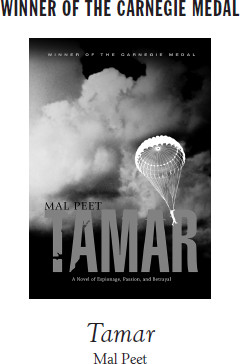

“A fifteen-year-old girl named Tamar receives a box from her grandfather who has committed suicide. In it are clues to her grandfather’s past and her own identity, but she must go on a journey to make sense of the clues. . . . An elegant work that is both a historical novel and a reflection on history. . . . Simply superb.”—

“A fifteen-year-old girl named Tamar receives a box from her grandfather who has committed suicide. In it are clues to her grandfather’s past and her own identity, but she must go on a journey to make sense of the clues. . . . An elegant work that is both a historical novel and a reflection on history. . . . Simply superb.”—

Kirkus Reviews

(starred review)

“Tension mounts incrementally in an intricate wrapping of wartime drama and secrecy. . . . This powerful story will grow richer with each reading.”

“Tension mounts incrementally in an intricate wrapping of wartime drama and secrecy. . . . This powerful story will grow richer with each reading.”

— Booklist

(starred review)