Life in a Medieval Castle (15 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Castle Online

Authors: Joseph Gies

Ecclesiastical as well as lay landlords established their own preserves. In the twelfth century Abbot Samson of Bury St. Edmunds, according to Jocelin of Brakelond, “enclosed many parks, which he replenished with beasts of chase, keeping a huntsman with dogs; and upon the visit of any person of quality, sat with his monks in some walk of the wood, and sometimes saw the coursing of the dogs; but I never saw him take part in the sport.” Other prelates joined in the hunt.

An exception to forest law was provided for the earl or baron traveling through a royal forest. Either in the presence of a forester, or while blowing his hunting horn to show that he was not a poacher, he was allowed to take a deer or two for the use of his party. The act was carefully recorded in the rolls of the special forest inquisitions under the title “Venison taken without warrant.” A roll of Northamptonshire of 1248 read:

The lord bishop of Lincoln took a hind and a roe in Bulax on the Tuesday next before Christmas Day in the thirtieth year

[of the reign of Henry III]. Sir Guy de Rochefort took a doe and a doe’s brocket [a hind of the second year] in the park of Brigstock in the vigil of the Purification of the Blessed Mary in the same year…

Deer killed with the king’s permission were listed as “venison given by the lord king”:

The countess of Leicester had seven bucks in the forest of Rockingham of the gift of the lord king on the feast of the apostles Peter and Paul…Aymar de Lusignan had ten bucks in the same forest…Sir Richard, earl of Cornwall, came into the forest of Rockingham about the time of the feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Mary, and took beasts in the park and outside the park at his pleasure in the thirty-second year…Sir Simon de Montfort had twelve bucks in the bailiwick of Rockingham of the gift of the lord king about the time of the feast of St. Peter’s Chains in the thirty-second year.

The records of the forest courts were full of dramatic episodes.

A certain hart entered the bailiwick of the castle of Bridge by the postern; and the castellans of Bridge took it and carried it to the castle. And the verderers on hearing this came there and demanded of Thomas of Ardington, who was then the sheriff, what he had done with the hart…The township of Bridge was attached for the same hart.

Sir Hugh of Goldingham, the steward of the forest, and Roger of Tingewick, the riding forester,…perceived a man on horseback and a page following him with a bow and arrows, who forthwith fled. Wherefore he was hailed on account of his flight by the said Hugh and Roger; and he was followed…and taken, as he fled, outside the covert, with his surcoat bloody and turned inside out. He was asked whence that blood came, and he confessed that it came from a certain roe, which he had killed…

When Maurice de Meht, who said that he was with Sir Robert Passelewe, passed in the morning with two horses through the town of Sudborough, he saw three men carrying a sack…And when the aforesaid three men saw him following them, they threw away the sack and fled. And the said Maurice de Meht took the sack and found in it a doe, which had been flayed, and a snare, with which the beast had been taken…

Clerical as well as lay hunters became embroiled with the law or with their neighbors. In 1236 at the coronation of Queen Eleanor, the earl of Arundel was unable to take part in the ceremony because he had been excommunicated by the archbishop of Canterbury for seizing the archbishop’s hounds when the archbishop hunted in the earl’s forest.

In 1254 a poacher, in the employ of the parson of Easton, was imprisoned for taking a “beast” in the hedge of Rockingham Castle. Freed from prison on pledge, the poacher died, but the parson, Robert Bacon, who had apparently also taken part in the hunt, and Gilbert, the doorkeeper of the castle, were ordered to appear. At the hearing Sir John Lovet, a forest official who may have been bribed by the accused, declared that the “beast” was not a deer but a sheep. The accused men were acquitted, but John Lovet was imprisoned for contradicting his own records, and released only after the payment of a fine of twelve marks.

One night in 1250 foresters found a trap in Rockingham Forest and nearby heard a man cutting wood. Lying in wait, they surprised Robert Le Noble, chaplain of Sudborough, with a branch of green oak and an axe. The next morning they searched his house and found arrows and a trap that bore traces of the hair of a deer. The chaplain was arrested at once and his chattels, wheat, oats, beans, wood, dishes, and a mare were seized as pledges for his appearance before the forest eyre. Another cleric was one of a company that spent a day in 1272 shooting in the forest, killing eight

deer. Cutting off the head of a buck, they stuck it on the end of a pole in a clearing and put a spindle in its mouth, and in the words of the court rolls, “they made the mouth gape towards the sun, in great contempt of the lord king and his foresters.”

Sometimes malefactors used clerical privilege to obtain release from prison, as when in 1255 one Gervais of Dene, servant of John of Crakehall, archdeacon of Bedford and later the king’s treasurer, was arrested for poaching and lodged in the prison of Huntingdon. The vicar of Huntingdon, several chaplains, and a servant of the bishop of Lincoln came to the prison armed with book and candle, claiming that Gervais was a clerk and threatening to excommunicate the foresters. Taking off the prisoner’s cap, they exposed a shaven head. Gervais was allowed to escape, though the foresters suspected that he had been shaved that day in prison. But at the forest eyre of Huntingdon in 1255 John of Crakehall was fined ten marks for harboring Gervais, who along with the vicar was turned over to the archdeacon of Huntingdon to deal with.

Usually the sons of knights or freeholders, foresters often abused their powers for gain—felling trees, grazing their own cattle, embezzling, taking bribes, extorting “sheaves, cats, corn, lambs and little pigs” from the people at harvest time (although specifically forbidden to do so by the Forest Charter), and killing the very deer they were supposed to protect. Not only the people who lived within the royal forests, but the nobles suffered. Matthew Paris complained that a knight named Geoffrey Langley, marshal of the king’s household, made an inquisition into the royal forests in 1250 and

forcibly extorted such an immense sum of money, especially from nobles of the northern parts of England, that the amount collected exceeded the belief of all who heard of it…The aforesaid Geoffrey was attended by a large and well-armed retinue, and if any one of the aforesaid nobles

made excuses…he ordered him to be at once taken and consigned to the king’s prison…For a single small beast, a fawn, or hare, although straying in an out-of-the-way place, he impoverished men of noble birth, even to ruin, sparing neither blood nor fortune.

Villagers in forest areas were supposed to raise the “hue and cry” (shouting when a felony was committed and turning out with weapons to pursue the malefactor) when an offense had been committed against the forest law. But their sympathies were often with the poachers. Again and again the rolls of the forest courts record the statements of the neighboring villages that they “knew nothing,” “recognized nobody,” “suspected no one,” “knew of no malefactor.”

Forest officers were a hated class. A Northamptonshire inquisition of 1251 recorded an exchange between a verderer and an acquaintance he met in the forest who refused to greet him, declaring, “Richard, I would rather go to my plow than serve in such an office as yours.”

Many of the accounts of the forest inquests have the ring of Robin Hood, whose legend, significantly, sprang up in the thirteenth century. In May 1246 foresters in Rockingham Forest heard that there were poachers “in the lawn of Beanfield with greyhounds for the purpose of doing evil to the venison of the lord king.” After waiting in ambush, they

saw five greyhounds, of which one was white, another black, the third fallow, a fourth black spotted, hunting beasts, which greyhounds the said William and Roger [the foresters] seized. But the fifth greyhound, which was tawny, escaped. And when the aforesaid William and Roger returned to the forest after taking the greyhounds, they lay in ambush and saw five poachers in the lord king’s demesne of Wydehawe, one with a crossbow and four with bows and arrows, standing at their trees. And when the foresters perceived them, they hailed and pursued them.

And the aforesaid malefactors, standing at their trees,

turned in defense and shot arrows at the foresters so that they wounded Matthew, the forester of the park of Brigstock, with two Welsh arrows, to wit with one arrow under the left breast, to the depth of one hand slantwise, and with the second arrow in the left arm to the depth of two fingers, so that it was despaired of the life of the said Matthew. And the foresters pursued the aforesaid malefactors so vigorously that they turned and fled into the thickness of the wood. And the foresters on account of the darkness of the night could follow them no more. And thereupon an inquisition was made at Beanfield before William of Northampton, then bailiff [warden] of the forest, and the foresters of the country…by four townships neighboring…to wit, by Stoke, Carlton, Great Oakley, and Corby.Stoke comes and being sworn says that it knows nothing thereof except only that the foresters attacked the malefactors with hue and cry until the darkness of night came, and that one of the foresters was wounded. And it does not know whose were the greyhounds.

Carlton comes, and being sworn, says the same.

Corby comes, and being sworn, says the same.

Great Oakley comes, and being sworn, says that it saw four men and one tawny greyhound following them, to wit one with a crossbow and three with bows and arrows, and it hailed them and followed them with the foresters until the darkness of night came, so that on account of the darkness of night and the thickness of the wood it knew not what became of them…

The arrows with which Matthew was wounded, were delivered to Sir Robert Basset and John Lovet, verderers.

The greyhounds were sent to Sir Robert Passelewe, then justice of the forest.

Matthew died of his wounds, and a later inquisition revealed that Matthew’s brother and two other foresters had seen the same three greyhounds in April when dining with the abbot of Pipewell, and that they belonged to one Simon of Kivelsworthy, who was thereupon sent to Northampton to be imprisoned. The abbot of Pipewell had to

answer before the justices for harboring Simon and his greyhounds. The case was later brought before the forest eyre in Northampton in 1255, where Simon proved that his greyhounds “were led there by him at another time but not then,” and was released after paying a fine of half a mark. The real culprit was never found.

The Villagers

Quoth Piers Plowman, “By Saint Peter of Rome!

I have an half acre to plow by the highway;

Once I have plowed this half acre and sown it after,

I will wend with you and show you the way…

I shall give them food if the land does not fail,

Meat and bread both to rich and to poor, as long as I live,

For the love of heaven; and all manner of men

That live through meat and drink, help him to work wightly

Who wins your food

…”

And would that…Piers with his plows…

Were emperor of all the world, and then perhaps all men would be Christian!

Though many castles were built inside towns for political and strategic reasons, the castle was rooted economically in the countryside. It was connected intimately with the village and the manor, the social and economic units of rural Europe. The village was a community, a collective

settlement, with its own ties, rights, and obligations. The manor was an estate held by a lord and farmed by tenants who owed him rents and services, and whose relations with him were governed by his manorial court. A manor might coincide with a village, or it might contain more than one village, or a village might contain parts of manors or several entire manors.

The manor supplied the castle’s livelihood. The word “manor” came to England with the Conqueror, but the arrangement was centuries old. On the Continent, it was used to provide a living for the knight and his retainers at a time when money was scarce.

A great castle such as Chepstow commanded a large number of manors, often widely scattered and interspersed with land belonging to other lords. The kind of settlement and cultivation on these manors depended on their location. On most of the plain of northern Europe, and in England in a band running southwest from the North Sea through the Midlands to the English Channel, the land lay in great open stretches of field broken here and there by stands of trees and the clustered houses of villages. This was “champion” (“champagne,” open field) country. Contrasting with it was the “woodland” country of Brittany and Normandy and the west, northwest, and southeast of England, where small, compact fields were marked off with hedges and ditches, and the farmhouses were scattered in tiny hamlets.

In champion country, the villages were large, with populations of several hundred. The surrounding fields were divided into either two or three sectors, farmed according to a traditional rotation of crops. In each sector every villager held strips of land, alongside and mixed in with those of his fellows and those of the lord. Land usually descended to the eldest son, but younger brothers and sisters could stay on and work for the heir, as long as they remained unmarried. Many younger sons of champion country left home to seek

their fortunes in the cities, or became mercenary soldiers.

In woodland country, on the other hand, each man worked his own separate farm. Land passed to all the surviving sons, who held and worked it together, living in a single large house or in a small group of adjoining houses. Tenants combined to perform labor service for their lord, but the system of inheritance made responsibility for services harder to assign. In consequence, woodland farmers tended to pay money rents instead of performing services, while in champion country the feudal work obligation tended to be the rule.

The village of champion country was typically a straggle of houses and farm buildings that had grown up along an existing road, but sometimes simply developed by itself, the paths between buildings and fields and adjacent villages over the centuries becoming worn and sunken to form the village streets. If there was a manor house, this large building, a lesser form of the castle hall, dominated the scene, along with the parish church, which on varying occasions served as storehouse, courthouse, prison, and fort. For the men in the fields, its bell sounded the alarm as well as the celebration of the mass. In its yard the villagers gathered to gossip, dance, and play games, and to hold fairs and markets.

Except in areas where stone was plentiful, houses were built of wattle and daub, that is, of timber framework supporting oak or willow wands covered with a mixture of clay, chopped straw or cow-hair, and cow-dung. In England the timber was most commonly oak. Sometimes a trunk and main branch of a tree were first trimmed of branches, then felled, split, and reassembled to form an arched “cruck” truss supporting roof and walls, strengthened with beams. The roofs were thatched. Houses were easily built, and could easily be moved—or destroyed; thieves were known to dig through house walls. The smallest huts consisted of a

single room, and even in the largest, most of the household ate and slept together in the main room, still another version of the hall, with an open hearth in the middle and a smoke vent in the roof. The floor, usually of beaten earth, was covered with rushes. Sometimes there was a separate room for the owner, sometimes even one for the old grandparents, or part of the family might sleep in a loft reached by ladder and trapdoor. Typically the cattle were housed at one end of the building, under the same roof. The kitchen was often in a separate building, or in a lean-to.

A peasant’s possessions consisted of three or four benches and stools, a trestle table, a chest, one or two iron or brass pots, a little pottery ware, wooden bowls, cups, and spoons, linen towels, wool blankets, iron tools, and, most important, his livestock. A reasonably prosperous villager owned hens and geese, a few skinny half-wild razor-backed hogs, a cow or even two, perhaps a couple of sheep, and his pair of plow oxen.

Outside the house, chickens scratched in the little farmyard (toft or messuage) containing one or two outbuildings, in the rear of which lay a garden plot, or croft, that the householder could farm as he pleased.

Contrary to widespread impression, the villagers of the thirteenth century were not limited to subsistence farming. They grew crops for their own households, for their payments to the lord, and sometimes for cash sales to markets. In England wheat was usually a cash crop, to be sold to pay for the money rents and taxes of the peasant household, while barley, oats, and rye were grown mainly for home consumption. Not all grains were baked into bread; some were brewed into ale. Peas and beans were usually boiled into soup. Other vegetables grew in the garden patches of the tofts and crofts—onions, cabbages, leeks. Staple crops were sown twice a year: wheat and rye in the fall, and barley, vetches, oats, peas, and beans in early

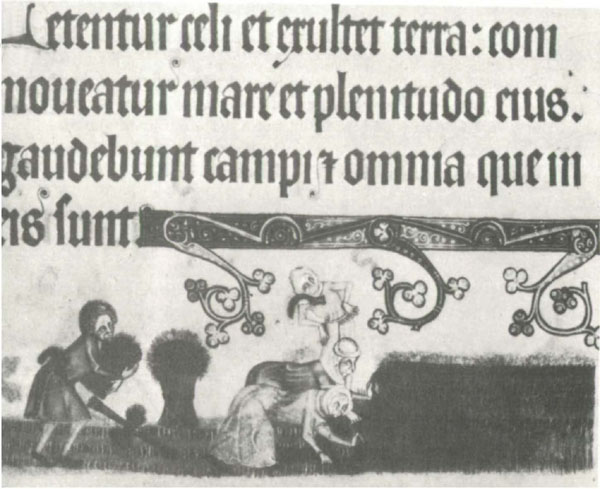

Reaping, from the Luttrell Psalter. (Trustees of the British Museum. MS. Add. 42130, f. 172v)

spring. Crops matured and were harvested in August and September.

Agricultural technology, if limited and unimaginative by the standards of a later age, was not entirely static despite the lack of scientific knowledge. The thirteenth-century farmer employed three ways to restore and improve the soil: by fallowing, that is, letting a field rest for a year; by marling, spreading a clay containing carbonate of lime; or by using sheep or cattle manure. But marl was scarce, and shortage of feed limited the number of animals and the

supply of manure. To feed his cattle, the farmer had only the grass that grew in the commonly-held “water meadows,” wetlands left untilled, and the stubble of the harvested fields. The advantages of planting grasses or turnips specifically for cattle feed were not yet perceived. The result was that there was never enough feed to see the livestock through the winter, and some had to be slaughtered every fall, in turn limiting the supply of manure for spring fertilizing. The technique of growing crops of clover and alfalfa to be plowed into the soil as fertilizer also was unknown.

For fallowing, the chief means of restoring the fields’ fertility, the villagers used crop rotation in either the ancient two-field or the newer three-field system. In the latter, one field was plowed in the fall and sown with wheat and rye. Each villager planted his own strip of land, all with the same seed. In the spring a second field was plowed and sown to oats, peas, beans, barley, and vetches. A third field was left fallow from harvest to harvest. The next year the field that had been planted with wheat and rye was planted with the oats, barley, and legumes; the fallow field was planted with wheat and rye; and the field that had grown the spring seed was left fallow.

In the older but still widely used two-field system, one field was left fallow and the other tilled half with winter wheat and rye, half with spring seed. The next year the tilled field lay fallow and the fallow field was tilled, with winter and spring crops alternating in the sections that were planted.

The plowman was the common man of the Middle Ages, Piers Plowman, guiding his heavy iron-shod plow, sometimes mounted on wheels to make it go more evenly, cutting the ground with its coulter, breaking it with its share, and turning it over with its wooden mould-board. The medieval husbandman plowed in long narrow strips of “ridge and furrow,” starting just to one side of the center line of his

piece of land, plowing the length of the strip, turning at the end and plowing back along the other side, and continuing around. In the wet soil of northern Europe, this ridge-and-furrow plowing helped free the soil from standing water that threatened to drown the grain. Peas and beans were planted in the furrow, grain on the ridge. The ancient pattern of ridge and furrow can still be seen in England in fields long abandoned to grazing.

The husbandman’s plow was drawn by a team of oxen whose number has provided a tantalizing mystery for scholars. Manorial records in profusion refer to teams of eight oxen, but pictorial representations nearly always show a more credible two, or occasionally four. Two men operated the plow, the plowman proper grasping the plow handles, or stilts, while his partner drove the oxen, walking to their left and shouting commands as he used a whip or goad. Behind followed men and women who broke up the clods with plow-bats or, in planting time, did the sowing.

On occasion villages increased their area under cultivation either by sowing part of the field that would normally have lain fallow or by making

assarts

, bringing wasteland under the plow. Such important measures were executed only with the agreement of all the villagers, and the land thus gained was shared equally.

Equality, in fact, was the guiding principle in the village, within the limits of two basic social classes: the more prosperous peasants, whose land was sufficient to support their families, and the cottars, who had to hire out as day-laborers to their better-off neighbors. The better-off villagers commonly held a “yardland” or a “half-yardland” (thirty or fifteen acres, or, in the terminology of northern England, two

oxgangs

or one

oxgang

). Along with these holdings went a portion of the village meadow, about two acres, the location decided by an annual lottery. At the lower end of the scale, the cottars held five acres of land or less; they had to borrow oxen from their neighbors for

plowing, or were even forced to “delve,” that is, cultivate with a spade. At least half an average village’s holdings were in the cottar class, too small to feed a family and requiring the supplement of income gained by hiring out. In some demesnes the lord’s land was cultivated chiefly or even entirely by such hired labor.

A second distinction among the villagers was based on personal rather than economic status: They were either free or non-free. Most of the villagers, whether half-yardlanders or cottars, were non-free, or villeins (the term “serf” was less common in England), which meant mainly that they owed heavy labor service to their lords: “week’s work,” consisting of two or three days a week throughout the year. A villein had other disabilities—he was not protected by the royal courts, but was subject to the will of his lord in the manorial courts; he could not leave his land or sell his livestock without permission; when his daughter married, he had to pay a fee; when he succeeded to his father’s holding, he paid a “relief,” or fine, and also a

heriot

, usually the best beast of the deceased. Most important, however, in an age of limited technology, when every hour’s work was precious, was the compulsion to work on the lord’s lands, plowing, mowing hay, reaping, shocking and transporting grain, threshing and winnowing, washing and shearing the lord’s sheep. By the thirteenth century labor services were often commuted into money payments. But in cash or kind, approximately half of all the villein’s efforts ultimately went, in one way or another, to the lord’s profit.

The rents and services of a villein were described in the manor custom books, often in elaborate detail: how much land the tenant was to plow with how many oxen, whether he was to use his own horse and harrow, or fetch the seed himself from the lord’s granary. Usually there were special rents for special rights—a hen at Christmas (the “woodhen”) in return for dead timber from the lord’s wood, or the right to pasture cattle on some of the lord’s land in return

for a plowing. At certain times of crisis during the year the lord could call on all of his tenants—free and unfree—to leave their own farming and work for him, plowing, mowing, or reaping. These movable works, called

boons

or

benes,

were the longest preserved of all work services. In return, the lord gave food, drink, or money, or sometimes all three. Benes were classified accordingly—the

alebidreap

and the

waterbidreap,

when the lord gave ale or water; the

hungerbidreap,

when the villagers were obliged to bring their own food; the

dryreap,

when there was no ale. The food donated by the lord was generally plentiful—meat or fish, pea or bean soup, bread and cheese. In theory these benes were done for the lord out of love—they were “love-boons”—as for any neighbor that needed help, like the community effort of a barn-raising or a town bee. Like these, they were the occasion of social gatherings. A characteristic feature was the “sporting chance”; at the end of the working day the lord gave each hay-maker a bundle of hay as large as he could lift with his scythe, or a sheep was loosed in the field, and if the mowers could catch it they could roast it.