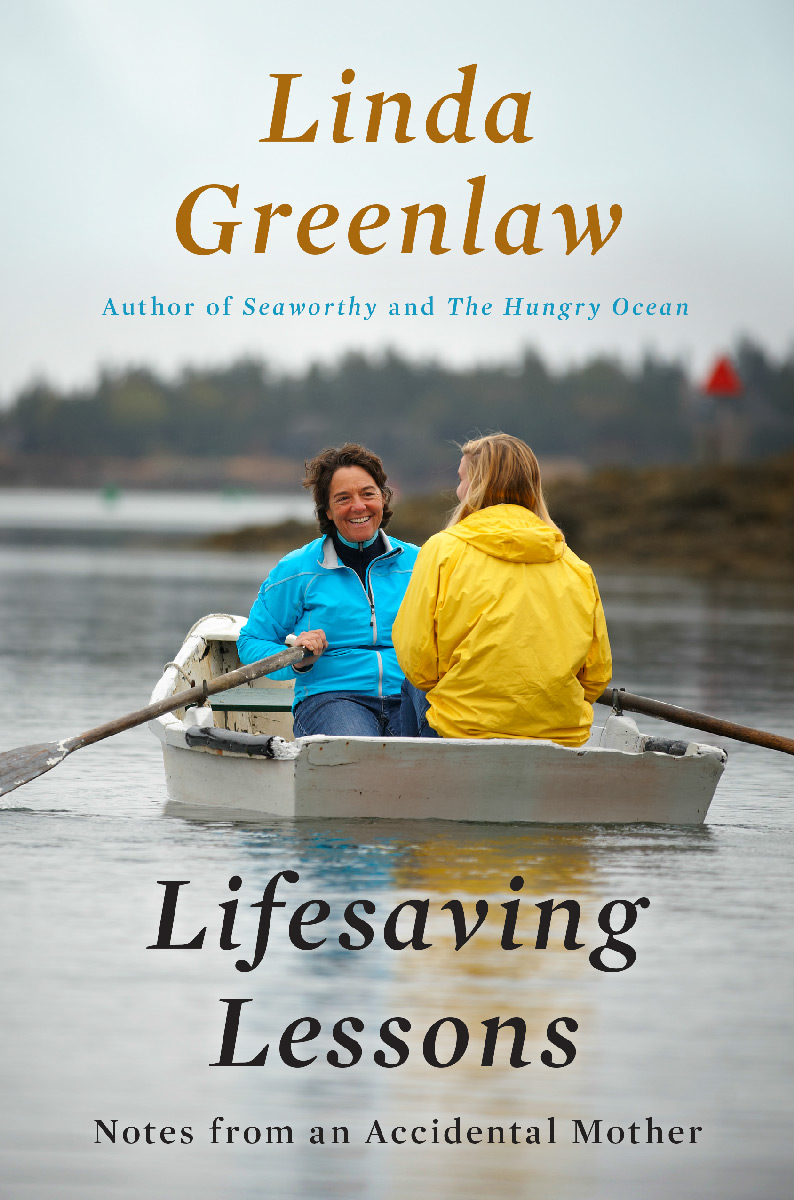

Lifesaving Lessons

Read Lifesaving Lessons Online

Authors: Linda Greenlaw

ALSO BY LINDA GREENLAW

The Hungry Ocean

The Lobster Chronicles

All Fishermen Are Liars

Slipknot

Fisherman's Bend

Seaworthy

Recipes from a Very Small Island (with Martha Greenlaw)

The Maine Summers Cookbook (with Martha Greenlaw)

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008 Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhiâ110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North 2193, South Africa

Penguin China, B7 Jaiming Center, 27 East Third Ring Road North, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100020, China

Â

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Â

First published in 2013 by Viking Penguin,

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Â

Copyright © Linda Greenlaw, 2013

All rights reserved

Â

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Greenlaw, Linda, 1960-

Lifesaving lessons : notes from an accidental mother / Linda Greenlaw.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-101-60602-5

1. Greenlaw, Linda, 1960- 2. Foster mothersâMaineâBiography. 3. Foster childrenâMaine. I. Title.

HQ759.7.G74 2013

306.874âdc23 2012028974

Â

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author's rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Â

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author's alone.

Â

Certain names and identifying characteristics of individuals have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

This book is dedicated to my wide yet tight group of friends, family, and community.

C

onfrontation was imminent. I didn't recall ever fighting with

my

mother the way Mariah and I are now. But I was a different kid. Weird, Mariah would say. The heated arguments she and I were having, I was certain, shook me harder and had more lasting effects on me than they did on the 120-pound fifteen-year-old spitfire who was now quickly closing the gap between us. Mariah seemed to thrive on drama while I cowered from itâit was a mismatched battle at best. When I complained to girlfriends more experienced in the rearing of daughters, they assured me that whatever tiff Mariah and I had gone through was nothing compared to those they had experienced, and that

all

of this was absolutely normal. My girlfriends did not understand.

Maybe if I ignore her, she'll walk right by and leave me in peace to clean and paint the bottom of the skiff I was now forcing my attention onto. She would never offer to help. That was out of the question. No, I thought, Mariah did not seem to have the gene for motivation. It used to bother me that she could lie on the couch and watch TV while I mowed the lawn, did dishes, or vacuumed the floor around her after I had put in a long day of fishing. But I had come to realize that the wrath of her disposition when asked to pitch in was not worth whatever assistance she rendered. I wondered if that made me an enabler. I squatted behind the upside-down boatâthe perfect shieldâand scraped tiny barnacles and dried green stuff from the waterline with a wide putty knife. There'll be no ignoring her, I thought as she drew near. She had me in her crosshairs and, it seemed, was trying to press her feet down through the earth with each step. I decided to put her off with a friendly greeting.

Casually looking up from my work, I brushed the blue dust of old antifouling paint from the cuffs of my shirt. I smiled and said, “Hi.” Mariah's arms were pumping as wildly as her legs and I could almost feel steam coming from her flared nostrils. I couldn't help but think that she looked like a charging bull. Her brown eyes flashed angrily. Her lips were pursed in a grimace that would repel the meanest junkyard dog, tail between its legs. Wow. I hadn't seen her so mad since I “ruined” her jeans by washing them. (How was I to know that the two-hundred-dollar dungarees were not intended to be laundered in the first six months of wear?) She stopped with the skiff between us, took a deep breath in preparation, and exhaled audibly. Oh yeah, she's pissed, I thought.

“Did you shut off my texting?” The syllables were like bullets fired from an automatic weapon: rapid, and individually articulated to avoid any doubt as to what was asked.

“Yes. First thing this morning,” I answered, bracing myself.

“Oh, that is so lame! Why?”

My immediate thought was that my mother would never have tolerated this tone from me. I couldn't imagine that Mariah needed to hear the reasons, yet again, for the no-texting rule. But I knew that if I did not respond quickly, she'd fill the void with total exasperation. “Because you didn't follow the rules. And we can't afford seven-hundred-dollar phone bills every month.”

“Your rules are unreasonable. This is totally unfair. And I told you that I would pay the overages.” We'd been down this road before. Repeat performance. Bad show. But here we go again, I thought. I went through all the justification I had used the last time I'd received an outrageous bill from the cell phone company, including the fact that I could look on the Internet to see with whom and at what time she was using her phone. Call me old-fashioned, but I think 3,700 text messages a month is excessive. Especially when the text messenger is a full-time student. I expected Mariah to turn her phone off only at the school's required lights-out time, which was 10:00 p.m. I didn't appreciate the 2:00 a.m. text marathons between Mariah and her boyfriend on weeknights. Math had never been my strong suit, but simple subtraction rendered a sum of five hours sleep each nightâmaximum. Should I mention her poor grades? I wondered.

“It's simple,” I said. “You broke the rules. You knew that you'd lose your freedom to text if you couldn't do it responsibly. Besides, how will you go about paying for your overages?”

“I'll use the support checks from my father. You said you wanted nothing to do with that money and that it was mine.”

“You're right. I did. Let's see, at this point you are already in arrears for the next five years of support checks. I think those payments terminate on your eighteenth birthday, which is in three years. The numbers don't add up.” I could see tears forming in Mariah's eyes. For a tough kid, she sure cried a lot.

“This is stupid!” I cringed at her use of an adjective that had been absolutely forbidden by my own mother. “You

have

to turn it back on. I can't live this way!” Now Mariah was sobbing uncontrollably. Her shoulders shook and her chest heaved. She gasped for a breath and changed tactics, blurting out, “There's nothing to do here. I'm bored!” Ouch, I thought. She knew how I detested her statements of boredom. I always took it so personally. It was as if she were telling me that

I

'

m

boring. And I am not. Bored? Really, everywhere I looked around my property I saw a project. I was literally surrounded by work. Bored? I'd love to be, even if just for a minute. I wish Mariah could teach me how to be that. No sense rising to that bait, I knew. Nothing good could come from it.

Maybe I didn't have the gene for mothering, but anyone's maternal instincts might naturally get confused by this stage of a child's development. I never knew how to deal with the crying. I wished I didn't see everything in black and white. I wished I could react with more compassion. If Mariah were younger, I'd probably hug her and stroke her hair until she stopped. I had no desire to hug her now. And she had no desire to be hugged.

There was an awkward silence, except for the sniffling. Weary and fearing going another round, I secretly wished Mariah would spin abruptly on her heel and stomp off as she always did. Why doesn't she sulk back to the house and watch

Gossip Girl

and read

Cosmopolitan

magazine? I picked up the masking tape and began to stretch it along the line where the skiff's blue and gray paint met. “You can't simply dismiss me like that! I am not a member of your crew!”

Well, that's for sure, I thought as I kept taping without looking up. “No member of my crew would ever talk to me like that.”

“Please turn my texting back on.” Now the tears had dried and Mariah's tone had changed from fighting to pleading. “I'll follow the rules this time. I promise.”

“No. I'm sorry. Last month was your third and final last chance. Your texting is off until I see your grades. And then, if we can have a civil discussion and come to some agreement about use, I may give you one more shot.”

“You cannot be serious! This is so stupid!” Mariah's face was getting red again. Here comes the next flood of tears, I thought. Her eyes darted wildly back and forth between me and the house. Oh, take the house, I thought. Please take the house. I knew from past experience that Mariah would eventually retreat and she'd miraculously be wearing a smile by lunchtime. But this time her departure would not be without a parting shot. In total frustration, she grabbed a quart of paint, then turned and hurled it into the woods so far that I wondered if I'd ever find it. “You are not my mother! I want to go home!”

An Island Life for Me

O

f course Mariah was right. I was not her mother. I had never had any children. I was the somewhat notoriously single and childless Linda Greenlaw. Although I am living what in my mind is a charmed life, even as I was cruising through my forties, I didn't have time for kids, or a husband for that matter. My childbearing and rearing years had been spent fully immersed in my life's work and greatest passion. They were spent at sea, chasing swordfish.

I never imagined that I would end up alone and childless. In fact, in my earlier years, I had always taken for granted that I would eventually re-create what

I

had had growing up: a loving, traditional family complete with hubby and kiddos. But things didn't quite work out that way. Consumed by, and in love with, the excitement and adventure and challenge of the life and lifestyle of commercial fishing since the age of nineteen, I always felt fulfilled in a way that might have upstaged the quest for mate and babies. I guess I thought I always had plenty of time for family. Middle age had sneaked up behind me while I was looking over the bow.

When I'm not offshore, I reside on Isle au Haut, a tiny island, with an even tinier population, off the coast of Maine. My life on the island is as salty as my life offshore in that I spend my time fishing for lobster, halibut, herring, or digging for clams, basically harvesting anything that swims or crawls around the shores surrounding my home. Of course I also write about these things, leaving me with a fairly short résumé: I fish, offshore and on, and I write about fishing. Writing is as solitary and antisocial as fishing. The solitude and remoteness of island existence and life at sea are conducive to prolific writing and are sources of material and stimulation. But those same attributes have stunted my personal relationships. The years I spent at sea, mostly thirty days at a time, didn't do much for my love life either. There's just something about “Thanks for dinner. See you in a month” that doesn't lead to a second date. All of this amounts to what I would call “family nonplanning.” Living on a remote outpost with tenuous ties (weather permitting) to mainline mainland hasn't done any more for the prospect of having my own family than my life at sea has. I didn't plan it that way. That's just the way it is. Ask anyone. They'll tell you that I am the woman who survived “the perfect storm.” And not only did I survive that devastating and life-taking weather event of 1991, but I also managed through my undying pragmatism to make the most of it. I have published, let's see, eight books, taking advantage of the spotlight Sebastian Junger put on me when he called me “one of the best captains, period, on the entire East Coast.” And the readers of my more memoirlike work will attest to the fact that I do not have children. When I lamented my single and childless status in

The Lobster Chronicles,

my older sister jokingly referred to the book as a 260-page personal ad. And as my status has not changed, I have to consider the possibility that it wasn't well written. I hear my fellow islanders whispering “old maid” comments that no longer embarrass me, so I guess I have progressed beyond that particular sensitivity. For that reason, when Mariah reminded me, in the heat of battle, that I was not her mother, I suppose an appropriate response aimed at her level would have been, “Duh.” But for your edification, let me explain how Mariah came to be on my cell phone bill in the first place. It all began on that same tiny island, just a few years ago.

The new guy hadn't been on the island long before the residents had all formed strong opinions. When you quite literally reside on a rock, seven miles from the mainland, with fewer than fifty other humans in the off-season, you get to know more about your neighbors than those who dwell in tamer, more populated areas. However, the trend toward more newcomers to the island leveled off when they didn't winter well. Most of them bailed out following their first icy, lonely season, and just when the rest of us were beginning to warm to them. Because of this, I hadn't had much to do with the new guy directly; it seemed like wasting time if he was going to leave anyway. My opinion of Ken Howard was based primarily on what friends and neighbors who had taken time to get to know him a bit had told me. They'd said he was a decent guy. Moving to Isle au Haut from Memphis, Tennessee, had been Ken's lifelong dream, and now, in his midforties, he was going for it. He had visited the island as a boy with his grandparents, and that visit had left such a profound impression that he spent nearly thirty years working to fulfill his dream. I had to respect that. And he had with him his ten-year-old niece, named Mariah. Ken, the story goes, had saved his niece from an existence of poverty, drugs, abuse, et cetera, bringing her to what he remembered as a paradise so that she, too, could have a dream to pursue. And with our island's one-room schoolhouse at its lowest attendance in years, anyone with a kid was welcomed with open arms. And hey, let's face it, the addition of an eligible bachelor who was no one's blood relative, was ambulatory, and could drive after dark was intriguing to some of us.

Three years into his being here, my firsthand interactions with Ken Howard hadn't gone beyond “Hi. Nice day.” I had learned that he was a recovering alcoholic, and he appeared to be sober when we had chance encounters. Ken had successfully weathered three tough winters, but one prevalent theory about new people who

do

stay is that they are misfits who can't survive in mainstream, orthodox civilization. And who wants to hang with weirdos? So between residents' not wanting to waste time on someone whom the odds are against staying long enough to get to know well enough to truly dislike, and the idea that anyone who does stay is a social oddball, new people have a tough row to hoe. I have a bumper sticker on my truck that reads, “Some of us are here because we're not all there.” So when Ken pulled into the end of my driveway one summer morning about two years after he moved to the island, I was perplexed. He climbed out of his VW Rabbit and I continued to focus on the pot warp I was measuring, cutting, and splicing while he strongly urged his niece to get out of the car. In all honesty, I couldn't recall seeing Mariah out of the vehicle since her arrival on Isle au Haut, unless it was in front of the school sitting on a swing, not swinging, just sitting. Because there are only thirteen miles of road on our island, and the price of gasoline is exorbitant, I supposed that if you like being in a car, you'll spend an inordinate amount of time just sitting in park. Whether it was the store parking lot or the area beside the Town Hall, Mariah seemed most content within the car, looking out. Well, we all thought, she was thirteenâand seemed perfectly thirteen in her nonamusement and disinterest in everyone and everything around her.

Now, as Ken cajoled Mariah to get out of the Rabbit, I pretended not to notice them out of politeness that could have easily been misconstrued as rudeness. After Ken pulled Mariah from her safe haven, I looked up from my work and called the usual greeting, which was met with a relieved smile and half wave from Ken and a frightened stare from the girl who appeared to be making a concerted effort to move slowly enough to remain behind her uncle.

Ken stomped out a cigarette in the dirt and waited for the young girl to catch up before speaking. “Mariah needs some work, and I was wondering if you had anything.” His voice was deep and sexy, and not at all compatible with the very thin man whose hair was too long and could have stood a good washing. I thought he looked better when he had first arrived on island. But sometimes Isle au Haut has that effect on people. Most of us get very casual about personal appearance. There's an overwhelming aura of “Who's going to see me anyway?” And “needs” seemed ill fitting when used in reference to employment for this waif of a preteen kid. “Do you need a sternman?” Ken continued. I held back a chuckle. “She's available tomorrow and every day until school starts up in the fall. She's a really hard worker. You're a great role model for her, Linda.” Although Ken's lack of a Maine accent clearly marked him as one “from away,” the black-and-red-plaid hunting shirt and missing front tooth placed him in good stead.

I had intended to fish my lobster traps alone this season, concentrating more on a newly acquired herring-seining business. But I did plan to hire someone to paint buoys and do a few odd jobs. “Do you want a job?” I asked, looking at Mariah directly for maybe the first time ever.

There was a short pause while I waited for Mariah to reply. Ken wasn't patient, and I supposed that came from knowing the girl as only a close relative could. I suspected that he feared what Mariah might say. “She does. She really does. And she's a great little worker. I just want to teach her the value of hard work and being productive. She hasn't had much of that in her past.” That seemed noble enough, I thought. I repeated my question.

I stared at Mariah, whose face was getting quite red, unsure whether the increased color was anger or total humiliation. She still hadn't opened her mouth, but she finally had to make eye contact. I shrugged and waited. Ken took a step to the side, eliminating the bit of protection she had. She took a deep breath, as if bracing herself for some trauma, exhaled loudly and said, “I guess.” I took that as a yes, and had a fleeting notion that the attitude might be an issue.

Never one to back away from a challenge, I said, “You can start painting buoys tomorrow. The paint and brushes are in the front of my truck.” I proceeded to show Mariah where to hang the wet buoys to dry, and told her that we'd begin setting lobster traps as soon as she had enough buoys ready. My new sternman looked as horrified as any indentured servant who suddenly realizes there is no escape.

“Thanks, Linda. She'll be here tomorrow morning, first thing. You won't be disappointed,” Ken said as he pulled a fresh pack of Marlboros from his shirt pocket. “Thank Linda, Mariah,” he advised the thoroughly disgusted girl.

“Thanks.” It was the longest, most exaggerated

Th

sound in history. She couldn't have been less sincere. It seemed that working for me might have been punishment for something. I had no idea what she had done to warrant what she clearly saw as torture. But I surely knew the value of hard work, and believed that the insolent teen might benefit from some. I hadn't seemed like much of a prospect as a commercial swordfisherman when I landed my first job on the deck of a boatâor “site,” as we sayâat the age of nineteen. Someone had given me a chance, and that had become my life's work and first love. And I despise painting buoys.

And so our relationship was born. It became abundantly clear that the only things that suited Mariah about working for me were the schedule and the paycheck. If I were to use a metaphor of my time being a writing project, I'd say that the bulk of the pages produced in early spring had been working on a new fishing venture: leaving lobster fishing small doodle space in the margins of life. I had acquired a herring-seining operation from my best friend, Alden, and had hoped to cash in on catching and selling herring to fellow lobster fishermen to use as bait. Spring is notoriously poor for lobster fishing, and it always appears that the only people making money are those selling bait. As a result, I never entered the margins to set or tend my traps until 10:00 a.m., which suited my new helper just fine. Most full-time, 800-trap fishermen work every day starting before the sun comes up until it sets, but our fishing duty was fairly light. I didn't set all my traps. We fished only 300, and hauled just four short days each week, hauling 150 traps each time we went out. Coupled with the fact that I had to spend some time writing, I

dabbled

in lobster fishing in comparison to the full-time guys whose only income comes from what they pull out of a trap.

I think it is fair to say that Mariah hated every second spent aboard my lobster boat,

Mattie Belle.

She hated the bait, handling the lobsters, picking crabs from traps, cleaning the boat, and she suffered from seasickness. That is not to say she wasn't good at all of it. In fact, she learned the moves quickly, and was one of the best helpers I ever hired. I never told her how to do anything. She watched me do something once, then dove in and took over. She watched how I used my legs to throw a trap high onto a stack, and did the same. She watched how I pulled a trap up onto the rail of the boat, clearing the line through the block, and mimicked me, pulling every other trap aboard. We seldom spoke. I do recall her saying on her first day, after throwing up for the first time, “I'll never like this.” And I still recall my reply being something to the effect that she would learn to love it. We didn't speak another word the rest of the day. She didn't have to say a word to communicate clearly to me that she found the entire experience excruciating. The whole summer long, Mariah would show up at the dock at the very minute required, not one second early or late. It was remarkable. Anyone could have set their watch by her bicycle's coasting down the hill leading to the float where I was always waiting for her in the skiff. The daily skiff ride to the mooring was perhaps the only time Mariah ever smiled during the course of the season. She would perch on the bow, face forward, and let the wind blow her thick, blond hair back straight, looking quite like the bowsprit Kate Winslet aboard the

Titanic

until we stopped alongside of the

Mattie Belle.

Her hair would fall, she would quickly gather it into a neat ponytail, exhale audibly in expectation of yet another day of misery, climb out of the skiff, and board the boat. She had her own boots and wore a set of my oilskins, not the highest fashion for a girl of her age who hadn't lazed into the island's casual sloppiness yet.

As the season wore on, Mariah and I did talk. Mostly it was my initiative. I understood that we had little in common and didn't want to be her friend. But I did become quite fond of her tenacity and tolerant of her poor attitude. I took seriously my part in role modeling. Mariah spent time with other island women, which was great as we all knew that her uncle could be everything except female. And every young girl needs to have adult women in her life, and without a mother around, the island women filled in expertly. Most of the mothering was done by my good friend and neighbor Brenda, which seemed entirely appropriate to me. Brenda looks and, well, just

is

more motherly than I am in that she engages in more feminine activities than I do and has raised both a daughter and a son. Before moving to the island from the Camden area, Brenda worked as a hair stylist and in a bank. Brenda is always neat as a pin in her personal appearance, even when she is helping her husband, Bill, in the stern of his boat, or collecting the island's trash to fulfill the contract they have with the town to do so. Brenda is also the island's librarian. Call me a sexist, but the stereotypical librarian is female, right? Whereas I was the adult tomboy still in fishing gear, Brenda was far from the dowdy stereotype. She's stylish to the point where I have always marveled at the perfection of her fingernails knowing that she picks crabmeat all summer. Come to think of it, Bill was a wonderful father figure for Mariah in that he shares good advice with those he sees in need (and in my opinion he is always spot on). Bill and Brenda each have families of their own from previous marriages, including several children and a couple of grandkids. Divorced, newly married, and fully established on Isle au Haut, they had all the experience I might have lacked in parenting. Mariah would go to Bill and Brenda's on a regular basis and bake cookies or do crafts or whatever girl things were occurring at the time. Mariah became close to Bill and Brenda, even calling them Grammy and Grampy, though they're not that much older than me. Isle au Haut has always been the epitome of how it takes a village to raise a child, even if there are only a handful of them on the island. And Mariah benefited from that in a big way.