Lincoln (12 page)

Authors: David Herbert Donald

Whigs welcomed Douglas’s initiative, for the internal improvements issue was neither sectional nor partisan. As the legislation moved through the House, more and more additions were made, in order to secure the support of those counties untouched by the main rail lines. Without making surveys or calling for expert advice, the legislature provided for loans up to $10,000,000 to construct a central railroad from Cairo to Galena; one major east-west line, the Northern Cross, connecting Jacksonville, Springfield, and Danville; and six spur lines connecting with the Cairo-Galena route. For the improvement of five rivers $400,000 was allotted, and those counties that benefited neither from railroads nor from river improvement were to receive $200,000. (The Illinois and Michigan Canal was funded under separate legislation.) The bill gave something to everybody.

Lincoln and the other members of the Long Nine strongly supported the measure. Though Lincoln was not a member of the committee that shaped the bill, he was frequently present during its deliberations, and on every roll call he and the rest of the Sangamon delegation voted for it and for all amendments expanding its scope. So did an overwhelming majority of all members of the state legislature. The law represented to them an ambitious but sensible program for the economic development of the state. Envying Massachusetts with its 140 miles of railroad in operation and Pennsylvania with its 218 miles of railroads and 914 miles of canals, nearly everyone agreed with the

Alton Telegraph

that the new legislation would be “the means of advancing the prosperity and future greatness of our state, as much as the birth of Washington did that of the United States.”

The panic of 1837 put an end to these high hopes and effectively killed the internal improvements plan. Very little construction was ever completed, and the state was littered with unfinished roads and partially dug canals. The state’s finances, pledged to support the grandiose plan, suffered, and Illinois bonds fell to 154 on the dollar, while annual interest charges were more than eight times the total state revenues. Inevitably there was a search for scapegoats, and questions were raised about Lincoln’s role in promoting such a harebrained and disastrous scheme.

Such criticism was misplaced. It was not stupid or irresponsible to support the internal improvements plan. Had prosperity continued, it might have done as much for the prosperity of Illinois as the construction of the Erie Canal did for that of New York. Nor was it fair to blame Lincoln for the

enactment of the legislation. Certainly he favored and supported it, but he was not a prime mover behind the bill. If any person could claim that role, it was Stephen A. Douglas.

Later some critics opposed to the internal improvements scheme suggested that Lincoln and the other members of the Long Nine supported it only as a means to secure the removal of the state capital to Springfield. In the next session of the legislature General W. L. D. Ewing charged “that the Springfield delegation had sold out to the internal improvement men, and had promised their support to every measure that would gain them a vote to the law removing the seat of government.” But neither Lincoln’s record nor that of the other members of the Long Nine showed a pattern of logrolling on the internal improvements legislation, and at the time there was no talk of a trade or a bribe.

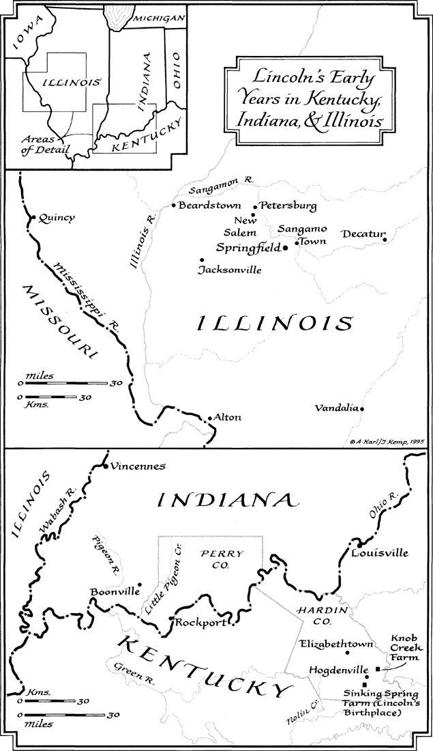

It was certainly true that the primary objective of the Long Nine was the relocation of the capital to Springfield. The selection of Vandalia, most people felt, had been a mistake; it was too small, too inaccessible, and, most important, too far south in a state where the central and northern regions were growing most rapidly. But Springfield had rivals, for Alton, Jacksonville, Peoria, and other towns also recognized that relocation of the capital meant huge increases in land values, much new construction, and many jobs.

Those opposed to the choice of Springfield tried to whittle down the influence of the Sangamon delegation in the legislature. The leader in this maneuver was Usher F. Linder, the articulate and self-important representative from Coles County, who proposed splitting off the northwestern sections of Sangamon County, which was half the size of the state of Rhode Island, in order to create a new county, named after Martin Van Buren. The maneuver troubled Lincoln and the other members of the Long Nine, because a reduction in the number of Sangamon representatives at just this time would jeopardize Springfield’s chances. They countered by proposing that the new county be carved out of Morgan County as well as Sangamon County, knowing that the representatives of Jacksonville, in Morgan County, would oppose it. Referred to a committee of which Lincoln was chairman, the bill passed the house despite his negative report, but it was killed in the senate. That was exactly what Lincoln had hoped.

More serious was Linder’s threat to investigate the Illinois State Bank, located in Springfield, which would probably put that institution out of business and at the same time deliver a severe blow to Springfield’s chance to become the capital. Linder shared the general Democratic hatred of all banks and also opposed moving the capital to Springfield. Quickly friends of the bank rushed down from Springfield and supplied Lincoln with facts and ideas to defeat Linder’s proposal.

Thus armed, Lincoln on January 11, 1837, took the floor to make his first extended speech in the state legislature. A clumsy, poorly organized effort, it was in part an

ad hominem

attack on Linder’s haughty airs and entangled rhetoric. Lincoln claimed that the demand for an investigation was “exclusively the work of politicians,” whom he defined as “a set of men who have

interests aside from the interests of the people, and who, to say the most of them, are, taken as a mass, at least one long step removed from honest men.” Then he tried to remove the sting of his remarks by adding: “I say this with the greater freedom because, being a politician myself, none can regard it as personal.”

Clearly not at home in discussing the economic issues involved in banking, Lincoln resorted to demagogy. An investigation of the bank, he claimed, would encourage “that lawless and mobocratic spirit,... which is already abroad in the land, and is spreading with rapid and fearful impetuosity, to the ultimate overthrow of every institution, or even moral principle, in which persons and property have hitherto found security.”

Despite its imperfections, the speech helped Lincoln’s standing, both in the legislature and in the public press. The

Vandalia Free Press

published it in full, and Springfield’s

Sangamo Journal

reprinted it, with the editorial comment, “Our friend carries the true Kentucky rifle and when he fires he seldom fails of sending the shot home.”

A third legislative initiative may have been only indirectly connected with plans to block the transfer of the capital to Springfield. Since the first publication of William Lloyd Garrison’s

Liberator

in 1831, Southern states had been growing increasingly angry over the rise of antislavery in the North, and Southern legislatures began passing resolutions demanding the suppression of abolitionist societies, which they said were circulating incendiary pamphlets among the slaves. These complaints received a generally favorable hearing in most Northern states, and Illinois, with its population largely of Southern birth, was no exception. The legislature passed a set of resolutions condemning abolitionist societies and affirming that slavery was guaranteed by the Constitution. For the most part, support of the resolutions was nonpartisan, though Democrats were more vehement in favoring them than Whigs, and they were adopted by the rousing vote of 77 to 6. The only reason to suspect that the opponents of Springfield had a hand in shaping these resolutions was the major role that Linder played in sponsoring them—the same Linder who had tried to partition Sangamon County and to destroy the Illinois State Bank at Springfield. Doubtless he wanted to show that Springfield, on that line where Southern and Northern settlements in Illinois were beginning to touch, was far less sympathetic to the slave states, which absorbed so much of the produce of Illinois, than Alton or Vandalia.

If this was his plan, it succeeded, because two of the Sangamon delegation, Lincoln and Dan Stone, a Vermonter, voted against the resolutions. Because neither made any public statement at the time, the damage that their votes did to support for Springfield in southern Illinois was kept to a minimum. Only after the removal of the capital and an internal improvements bill were agreed on did Stone and Lincoln present a protest against the resolutions. It was a cautious, limited dissent. Instead of the resolution of the General Assembly declaring that “the right Of property in slaves, is sacred to the slave-holding States by the Federal Constitution,” Stone and Lincoln suggested, “The Congress of the United States has no power, under

the constitution, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the different States.” Where the General Assembly announced, “we highly disapprove of the formation of abolition societies, and of the doctrines promulgated by them,” the two Sangamon legislators voiced their belief “that the institution of slavery is founded on both injustice and bad policy; but that the promulgation of abolition doctrines tends rather to increase than to abate its evils.”

After defeating all efforts to undermine the influence of the Sangamon delegation, Lincoln and the other members of the Long Nine shepherded through the legislature the bill to move the capital. The maneuvering required a delicate touch, and Lincoln’s political skills were repeatedly tested. Several times it seemed that the bill to relocate the capital would meet certain defeat. On one occasion, in order to eliminate the smaller and poorer towns from the competition to replace Vandalia, Lincoln drafted an amendment requiring that the city selected must donate $50,000 and two acres of land for new state buildings; then, to keep it from being known that this was a move in the interest of Springfield, which could afford such a gift, he allowed the amendment to be introduced by a member from Coles County. Twice the bill was tabled, and it was, as Robert L. Wilson, one of the Long Nine recalled, “to all appearance... beyond resussitation [sic].” But Lincoln, Wilson reported, “never for one moment despaired but called his Colleagues to his room for consultation,” and gave each an assignment to lobby doubtful members. When debate was renewed, the outcome was still doubtful. To win further support Lincoln accepted two unimportant amendments and added one of his own: “The General Assembly reserves the right to repeal this act at any time hereafter.” It was in reality meaningless, for of course the legislature always had a right to repeal laws; but the change gave a plausible excuse to vote for the bill, which passed, 46 to 37. After that came the balloting on the site, and from the initial tally it was clear that Springfield had a strong lead. On the fourth ballot the work of the Long Nine paid off, and on February 28, Springfield received a clear majority of all the votes.

That night the victorious Sangamon delegation had a victory celebration, at Capp’s Tavern, to which all members of the legislature were invited. Cigars, oysters, almonds, and raisins disappeared rapidly, as did eighty-one bottles of champagne, for which the wealthy Ninian Edwards paid $223.50. Afterward there were further celebrations in Springfield and other parts of Sangamon County, which the Long Nine attended. At the Athens rally the toast was “Abraham Lincoln one of Natures Noblemen.”

When the legislature adjourned, Lincoln returned to New Salem to say good-bye to his old friends. In September two justices of the Illinois Supreme Court had licensed him to practice law, and on March 1 his name was entered on the roll of attorneys in the office of the clerk of the Supreme Court. On April 15, 1837, he removed to Springfield, where Stuart took him into partnership, and the two opened an office at No. 4 Hoffman’s Row.

Cold, Calculating, Unimpassioned Reason

O

n April 15, 1837, Lincoln rode into Springfield on a borrowed horse, with all his worldly possessions crammed into the two saddlebags. At the general store of A. Y. Ellis & Company on the west side of the town square, he inquired how much a mattress for a single bed, plus sheets and pillow, would cost. Joshua F. Speed, one of the proprietors, reckoned up the figures and announced a total of $17. Lincoln replied that was doubtless fair enough but that he did not have so much money. Telling Speed that he had come to Springfield to try an “experiment as a lawyer,” he asked for credit until Christmas, adding in a sad voice: “If I fail in this, I do not know that I can ever pay you.”