Lincoln (33 page)

Authors: David Herbert Donald

Lincoln was scarcely more successful in two eulogies he pronounced. Attending court in Chicago when Zachary Taylor died in July 1850, Lincoln was invited by members of the Common Council to memorialize the late President. “The want of time for preparation will make the task, for me, a

very difficult one to perform, in any degree satisfactory to others or to myself,” he replied, but he felt obliged to accept the assignment as a duty, which would incidentally keep his name before the growing population of northern Illinois. His address was largely a pedestrian recital of the facts of Taylor’s life, interrupted by an occasional rhetorical flourish: “And now the din of battle nears the fort and sweeps obliquely by;... they fly to the wall; every eye is strained—it is—it is—the stars and stripes are still aloft!”

Only slightly more successful was the eulogy Lincoln delivered in Springfield on Henry Clay. He genuinely admired the Kentucky statesman, and he was beginning to think of himself as Clay’s successor in leading a revitalized Whig party. But his analytical cast of mind kept him from indulging in effusive praise of anyone. Instead, he confined himself largely to a factual review of Clay’s career, which unintentionally revealed more about the speaker than his subject. Clay’s lack of formal education, Lincoln suggested in a clearly autobiographical passage, “teaches that in this country, one can scarcely be so poor, but that, if he

will,

he

can

acquire sufficient education to get through the world respectably.” Clay’s eloquence, he observed, did not consist “of types and figures—of antithesis, and elegant arrangement of words and sentences”; it derived its strength “from great sincerity and a thorough conviction, in the speaker of the justice and importance of his cause.” Precisely the same could be said of the best of Lincoln’s own productions.

Largely perfunctory, Lincoln’s eulogy on Henry Clay came alive only in its final paragraphs. Of the hundreds of funeral addresses’ on the Kentucky statesman, Lincoln’s was one of the very few that explicitly dealt with Clay’s views on slavery. Clay “did not perceive, that on a question of human right, the negroes were to be excepted from the human race,” Lincoln announced; consequently, “he ever was, on principle and in feeling, opposed to slavery.” Because Clay recognized that it could not be “at

once

eradicated, without producing a greater evil,” he supported the efforts of the American Colonization Society to transport African-Americans back to Africa and served for many years as president of that organization.

Endorsing Clay’s views on colonization, Lincoln revealed a change in his own attitude toward slavery. He had all along been against the peculiar institution, but it had not hitherto seemed a particularly important or divisive issue, partly because he had so little personal knowledge of slavery. But in Washington his strongly antislavery friends in Congress, like Joshua R. Giddings and Horace Mann, helped him see that the atrocities that occurred every day in the national capital were the inevitable results of the slave system. As Lincoln’s sensitivity to the cruelty of slavery changed, so did his memories. In 1841, returning from the Speed plantation, he had been

amused by the cheerful docility of a gang of African-Americans who were being sold down the Mississippi. Now, reflecting on that scene, he recalled it as “a continual torment,” which crucified his feelings.

He also began to understand the effect that slavery had on white Southerners. He took great interest in affairs in Kentucky, where his father-in-law, Robert S. Todd, along with Henry Clay, was working for gradual emancipation, which they hoped the Kentucky constitutional convention of 1849 would endorse. But the convention overwhelmingly rejected all plans to end slavery or even to ameliorate it. Todd, a candidate for the senate, died during the campaign; had he lived, he could have been disastrously defeated. These developments gave Lincoln a new insight into Southern society. Even nonslaveholders, who constituted an overwhelming majority of the Kentucky voters, were opposed to any form of emancipation. The prospect of owning slaves, he learned, was “highly seductive to the thoughtless and giddy headed young men,” because slaves were “the most glittering ostentatious and displaying property in the world.” As a young Kentuckian told him, “You might have any amount of land; money in your pocket or bank stock and while travelling around no body would be any wiser, but if you had a darkey trudging at your heels every body would see him and know that you owned slaves.”

Lincoln looked for a rational way to deal with the problems caused by the existence of slavery in a free American society, and he believed he had found it in colonization. Like Clay and Chief Justice John Marshall, who belonged to the American Colonization Society, he became convinced that transporting African-Americans to Liberia would defuse several social problems. By relocating free Negroes from the United States—and, at least initially, all those transported were to be freedmen—colonization would remove what many white Southerners considered the most disruptive elements in their society. Consequently, Southern whites would more willingly manumit their slaves if they were going to be shipped off to Africa. At the same time, Northerners would give more support for emancipation if freedmen were sent out of the country; they could not migrate to the free states where they would compete with white laborers. Moreover, colonization could elevate the status of the Negro race by proving that blacks, in a separate, self-governing community of their own, were capable of making orderly progress in civilization. Thus, Lincoln thought, voluntary emigration of the blacks—and, unlike some other colonizationists, he never favored forcible deportation—would succeed both “in freeing our land from the dangerous presence of slavery” and “in restoring a captive people to their long-lost father-land, with bright prospects for the future.”

The plan was entirely rational—and wholly impracticable. American blacks, nearly all of whom were born and raised in the United States, had not the slightest desire to go to Africa; Southern planters had no intention of freeing their slaves; and there was no possibility that the Northern states would pay the enormous amount of money required to deport and resettle

millions of African-Americans. From time to time, even Lincoln doubted the colonization scheme would work. He would like “to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia—to their own native land,” he announced in 1854. “But,” he added, “a moment’s reflection would convince me, that whatever of high hope, (as I think there is) there may be in this, in the long run, its sudden execution is impossible. If they were all landed there in a day, they would all perish in the next ten days; and there are not surplus shipping and surplus money enough in the world to carry them there in many times ten days.”

Though reality sometimes broke in, Lincoln persisted in his colonization fantasy until well into his presidency. For a man who prided himself on his rationality, his adherence to such an unworkable scheme was puzzling, though not inexplicable. His failure to take into account the overwhelming opposition of blacks to colonization stemmed from his lack of acquaintance among African-Americans. Of nearly 5,000 inhabitants of Springfield in 1850, only 171 were blacks, most of whom labored in menial or domestic occupations. Mariah Vance, who worked two days a week as a laundress in the Lincoln home and sometimes helped out with the cooking, was one of these; another was the Haitian, William de Fleurville, better known as “Billy the Barber,” whom Lincoln advised on several small legal problems. These were not people who could speak out boldly to say that they were as American as any whites, that they had no African roots, and that they did not want to leave the United States.

Lincoln’s persistent advocacy of colonization served an unconscious purpose of preventing him from thinking too much about a problem that he found insoluble. He confessed that he did not know how slavery could be abolished: “If all earthly power were given me, I should not know what to do, as to the existing institution.” Even if he had a plan, there was no way of putting it into effect. After the Compromise of 1850 both the Whig and the Democratic parties had agreed that, in Lincoln’s words, questions relating to slavery were “settled forever.” For a man with a growing sense of urgency about abolishing, or at least limiting, slavery, who had no solution to the problem and no political outlet for making his feelings known, colonization offered a very useful escape.

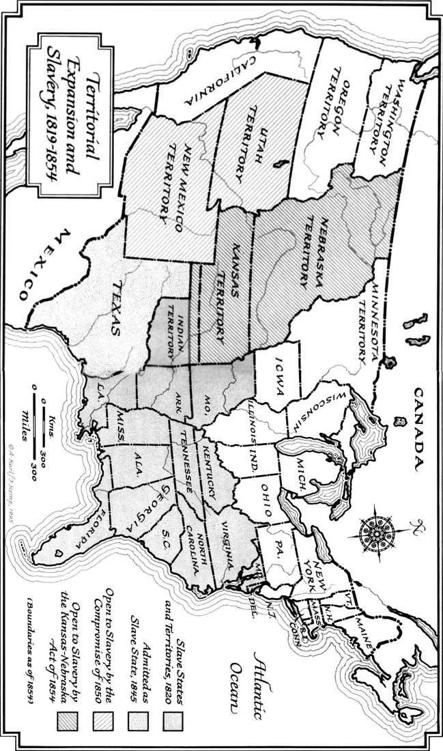

In 1854 reality replaced fantasy. On January 4, Stephen A. Douglas, the chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, introduced a bill to establish a government for the Nebraska Territory (which constituted the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase, including the present states of Kansas and Nebraska). The measure was much needed. Immigrants from Missouri and Iowa were already pushing across the border into the unorganized region, and a favored route for the proposed transcontinental railroad ran through Nebraska. Slavery had been prohibited in this area by the Missouri

Compromise of 1820, but Southerners, fearful of the growing population and wealth of the North, had killed previous efforts to organize Nebraska as a free territory. Douglas sought to avoid a similar fate for his new bill by providing that the territory, “when admitted as a State or States,... shall be received into the Union, with or without slavery, as their constitution may prescribe.” Taking these words from the 1850 acts organizing New Mexico and Utah, Douglas thus extended the doctrine of “popular sovereignty” to the Nebraska Territory. But because his measure said nothing about slavery in Nebraska during its territorial stage or about the Missouri Compromise restriction, proslavery senators pressed him to include an explicit repeal of the Missouri Compromise. Reluctantly he agreed, though he knew it would “raise a hell of a storm,” and at the same time he assented to the division of the region into two territories, Kansas and Nebraska. Endorsed by the Pierce administration, the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed by the Congress after a bitter struggle and became law on May 30.

This act, Lincoln said a few months later, “took us by surprise—astounded us We were thunderstruck and stunned.” His immediate actions suggested that he was more stunned than astounded. He made no comment, public or private, on the Kansas-Nebraska measure while Douglas, with brilliant parliamentary management and unrelenting ferocity toward his opponents, forced it through both houses of Congress. He said nothing about the “Appeal of the Independent Democrats,” drawn up by free-soil senators Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, with assistance from other antislavery congressmen, which assailed the repeal of the Missouri Compromise “as a gross violation of a sacred pledge; as a criminal betrayal of previous rights; as part and parcel of an atrocious plot to exclude from a vast unoccupied region immigrants from the Old World and free laborers from our own States, and convert it into a dreary region of despotism, inhabited by masters and slaves.” Certainly he read the congressional debates studiously, and he followed the crescendo of attacks on Douglas and his bill both in the

New York Tribune

and the

Chicago Tribune,

to which Lincoln & Herndon subscribed, and in the abolitionist papers, such as the

National Anti-Slavery Standard, Emancipator, and National Era,

which Herndon received. Herndon sent away for the speeches of antislavery spokesmen such as Sumner, Chase, and Senator William H. Seward of New York, and he regularly received those of Theodore Parker, the great Boston preacher, and Wendell Phillips, the abolitionist orator; and he made sure that his partner knew about them all. But Lincoln said and wrote nothing.

He was silent partly because he was extraordinarily busy at just the time the Kansas-Nebraska bill was working its way through the Congress. In addition to the demands of his regular legal practice, the suit of the

Illinois Central Railroad

v.

McLean County

was to be heard in the Illinois Supreme Court on February 28, and in the weeks before the hearing Lincoln spent all the time he could spare preparing his brief and his oral argument in a case

that was probably the most important and certainly was the most remunerative in his entire legal career.

As a private citizen, holding and seeking no public office, he did not feel called upon to make a public statement about the Kansas-Nebraska bill. Neither Douglas nor his measure would come directly before the Illinois electorate in 1854. The only general election that year was for state treasurer, whose selection would not depend on his support of or opposition to Kansas-Nebraska. In the fall there would, of course, be elections for representatives in Congress and for the members of the state legislature, but the political situation was so confused that it was not clear how Lincoln could make any meaningful intervention.