Lincoln (71 page)

Authors: David Herbert Donald

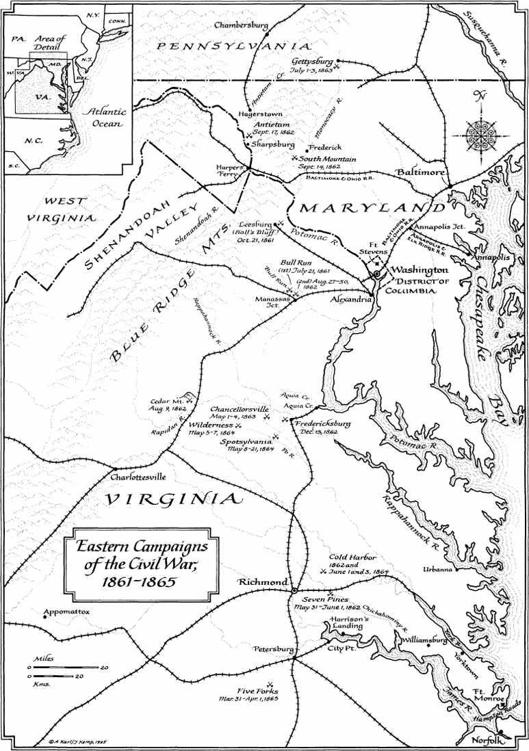

Harboring such doubts, Lincoln had stipulated that McClellan must not embark on his campaign without leaving behind a sufficient force to make Washington “entirely secure.” That requirement led to an unsolvable conflict between them. Lincoln was never able to make the general comprehend the political importance of the security of the national capital. McClellan, for his part, failed to convince the President that the best way to defend Washington was to attack Richmond.

Before leaving for the Peninsula, McClellan, as directed, held a council of war, and his corps commanders recommended that a force of 40,000 or 50,000 men was needed to protect the capital. McClellan believed he was

carrying out this directive by stationing 22,000 men in and around Washington and by posting other troops nearby—at Manassas, at Warrenton, in the Shenandoah Valley, and on the lower Potomac—all in close proximity if the capital should be attacked. But he never explained his thinking to Lincoln and, except for quickly passing a paper under Hitchcock’s nose, did not show anybody his troop disposition before he sailed for the Peninsula. Stanton, still new in his job and always highly nervous, feared for the safety of Washington and asked Hitchcock and General James Wadsworth, commandant of the forces in the capital, to verify that McClellan had followed the President’s order to leave the capital secure. Both agreed that he had not. On April 3, Lincoln ordered McDowell’s corps—approximately one-third of the army McClellan had hoped to muster on the Peninsula—held back for the defense of Washington.

After that there was endless bickering between McClellan and the civilian authorities in Washington. The general found the Confederates entrenched at Yorktown on the Peninsula and, as usual vastly overestimating the enemy’s strength, demanded reinforcement. Without McDowell’s men, he felt unable to carry the Confederate lines and settled down to besiege their fortifications. Impatiently Lincoln reminded him that, even after McDowell’s corps was held back, he had 100,000 troops at his command and suggested: “I think you better break the enemies’ line... at once.” Furious, McClellan wrote his wife, “I was much tempted to reply that he had better come and do it himself.”

Lincoln told Browning that he was “dissatisfied with McClellan’s sluggishness of action,” but he tried to soothe the general’s feeling with a fuller explanation why McDowell’s troops had been detained. For all his charity, he could not refrain from adding a word of self-justification: “You will do me the justice to remember I always insisted, that going down the Bay in search of a field, instead of fighting at or near Manassas, was only shifting, and not surmounting, a difficulty—that we would find the same enemy, and the same, or equal, intrenchments, at either place.” The President assured the general that he would do his best to sustain the army, and he ended with a warning:

“But you must act.

”

Relations between the general and his commander-in-chief were strained but not broken. After reevaluating the forces left to defend Washington, Lincoln detached Franklin’s division from McDowell’s corps and sent it to reinforce the army on the Peninsula. Grateful for this evidence of the President’s “firm friendship and confidence,” McClellan told Montgomery Blair that he was now convinced “that the Presdt had none but the best motives.” He promised soon to report a success that would be “brilliant, although with but little loss of life.”

On May 3, when the Confederates withdrew from Yorktown and McClellan began his long-planned advance up the Peninsula, Lincoln decided to move closer to the scene of operations. Accompanied by Chase and Stanton and escorted by General Egbert L. Viele, he boarded the Treasury Department’s new revenue cutter, the

Miami,

sailed down the Potomac, and the

next day arrived at Fort Monroe, where seventy-eight-year-old General John E. Wool commanded the garrison. After learning that McClellan would not join them because his army had just defeated the Confederates at Williamsburg and was pushing them back toward Richmond, the President and his associates decided that the time had come to liberate Norfolk, on the south side of the James estuary, where the hulking

Merrimack

was sheltered, still a threat to the Union navy.

Though the professional soldiers in General Wool’s command advised that it was impossible to land troops anywhere near Norfolk because shoals would prevent boats from getting closer than a mile to the shore, Chase was determined to see for himself and, using the

Miami

and a tugboat, got very near to land. He reported his finding to Lincoln, who had been studying the maps and thought he had discovered another landing site nearby. Under a bright moon Lincoln and Stanton sailed in the tugboat right up to the shore, while Chase aimed the long-range guns of the

Miami

to protect them if they were attacked. The President insisted on climbing out on what Virginians called their “sacred soil” and, in bright moonlight, strolled up and down on the beach.

After showing that a landing was possible, Lincoln did not participate in the invasion the next day but remained at Fort Monroe attending to other business. That evening he heard how Chase had gone ashore, led the Union troops, and received the surrender of Norfolk. A huge explosion told the President’s party that the

Merrimack,

abandoned by the Confederates, had been blown up. “So,” Chase wrote to his daughter, “has ended a brilliant week’s campaign of the President, for I think it quite certain that if he had not come down, [Norfolk] would still have been in possession of the enemy and the Merrimac as grim and defiant and as much a terror as ever.”

The episode was of no particular importance except perhaps to confirm the distrust of professional military men that both Lincoln and Stanton shared. But the President would not allow his little adventure to be used to McClellan’s discredit. Afterward, over dinner at General Wool’s headquarters, when someone made a slurring reference to the commander of the Army of the Potomac, Lincoln rebuked him: “I will not hear anything said against Genl. McClellan, it hurts my feelings.”

But McClellan, feeling victory almost within his grasp, was not so generous, and he insisted on reversing some of Lincoln’s recent decisions. He had never liked the corps arrangement that the President had forced him to accept and now, claiming that it “very nearly resulted in a most disastrous defeat” at Williamsburg, planned to remove “incompetent commanders” of corps and divisions. Reluctantly Lincoln allowed McClellan to suspend the corps organization, though he reminded the general that it was based “on the unanimous opinion of every

military man

I could get an opinion from, and every modern military book, yourself only excepted.” He warned McClellan that his actions would be perceived “as merely an effort to pamper one or two pets, and to persecute and degrade their supposed rivals” and asked whether he had considered the implications of reducing the rank

of Generals Sumner, Heintzelman, and Keyes all at once.

McClellan continued to complain that he did not have enough men to confront the overwhelming Confederate force. He never ceased asking Lincoln for McDowell’s army corps that had been held back to defend Washington (though he did not want McDowell himself, whom he regarded as an enemy who fed the Committee on the Conduct of the War material hostile to McClellan). Unwilling to leave Washington exposed, Lincoln thought he found a way to defend the capital while reinforcing McClellan: he would have McDowell’s corps advance overland toward Richmond in such a way as to connect with the right wing of McClellan’s forces on the Peninsula. But because he retained a residual distrust of McClellan’s judgment, he instructed McDowell to operate not as a part of McClellan’s force but as an independent cooperating army. As he expected, McClellan resisted the plan. He insisted that the reinforcements should be sent by water, and he announced that since he outranked McDowell that general would, under the sixty-second article of war, have to obey his orders.

To make sure McDowell understood his mission, the President went down to Aquia Creek, accompanied by Secretary Stanton and John A. Dahlgren, a naval officer to whom he had taken a great liking. When they reached the Potomac Creek, McDowell called their attention to a trestle bridge his men were erecting a hundred feet above the water in that deep and wide ravine. “Let us walk over,” exclaimed the President boyishly, and though the pathway was only a single plank wide, he led the way. About halfway across Stanton became dizzy and Dahlgren, who was somewhat giddy himself, had to help the Secretary. But Lincoln, despite the grinding cares of his office, was in fine physical shape and never lost his balance.

His political equilibrium was not so steady. By the end of May 1862 his administration could point to few successes. In neither the East nor in the West had Union armies succeeded in crushing the Confederate forces. Only in faraway Louisiana, where David G. Farragut ran the fortifications on the lower Mississippi River and seized New Orleans, had there been a clear Union success. The Treasury was almost depleted. After exhausting the possibilities of borrowing, Secretary Chase had reluctantly been obliged to ask Congress to issue legal-tender paper money (usually called greenbacks). Like Chase, Lincoln doubted the constitutionality of the measure, but he had no choice but to approve it. In foreign affairs, European powers had nearly exhausted their patience and, as cotton shortages caused massive unemployment and suffering in the textile mills, were coming close to recognizing the Confederacy. In Congress the President had almost no defenders, and a few Jacobin members of his own party criticized almost every action he took. The prospects for Lincoln’s presidency were not good. Edward Dicey, the perceptive American correspondent of the British journals the

Spectator

and

Macmillan’s Magazine,

offered what he felt would be the verdict of history: “When the President leaves the White House, he will be no more regretted, though more respected, than Mr. Buchanan.”

An Instrument in God’s Hands

W

henever Lincoln’s plans were frustrated, he reverted to the fatalism that had characterized his outlook since he was a youth. A delegation of Quakers known as Progressive Friends who visited him on June 20,1862, urging a proclamation to emancipate the slaves, found him in such a mood. At first he bandied words with them. Since he, as President, could not require obedience to the Constitution in the Southern states, could he be more effective in enforcing an emancipation proclamation? “If a decree of emancipation could abolish Slavery,” he argued, “John Brown would have done the work effectually.” Then, turning serious, he acknowledged to his visitors that he was “deeply sensible of his need of Divine assistance” in the troubles he and the country faced. He had sometimes thought that “perhaps he might be an instrument in God’s hands of accomplishing a great work and he certainly was not unwilling to be,” he told the memorialists. But he warned them: “Perhaps ... God’s way of accomplishing the end [of slavery] ... may be different from theirs.”

By the summer of 1862, Lincoln felt especially in need of divine help. Everything, it seemed, was going wrong, and his hope for bringing a speedy end to the war was dashed. In the West the Union drive to open the Mississippi River valley stalled after the capture of Corinth, Mississippi, and the key city of Vicksburg remained in Confederate hands. In Tennessee, Buell ignored the President’s orders to advance into the mountainous regions, and so failed to liberate the desperate Unionists of Appalachia. Federal

amphibious operations along the coasts and on the waterways, which had resulted in the seizure of New Orleans, the sea islands of South Carolina, and Cape Hatteras, seemed barren of results—except for endless bickering among factions of liberated Louisiana Unionists who demanded the President’s attention. And—most important of all—the news from McClellan and the Army of the Potomac was discouraging.