Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

Lion of Liberty (22 page)

On May 1, 1778, an aide rode into Washington's headquarters at Valley Forge with a letter from Benjamin Franklin in Paris that the French government had signed two treaties with the United States: the first, a treaty of amity and commerce, the second a treaty of alliance pledging direct French military aid to the United States once England declared war against France.

At Valley Forge, Washington proclaimed an official day of “public celebration,” beginning with religious services and followed by “military parades, marchings, the firings of cannon and musketry.”

25

Patrick Henry rejoiced at the news and predicted an early end to the war news: “I look at the past condition of America as at a dreadful precipice from which we have escaped by means of the generous French, to whom I will be everlastingly bound by the most heartfelt gratitude.”

26

25

Patrick Henry rejoiced at the news and predicted an early end to the war news: “I look at the past condition of America as at a dreadful precipice from which we have escaped by means of the generous French, to whom I will be everlastingly bound by the most heartfelt gratitude.”

26

Within weeks, Washington and his army left Valley Forge to attack the British and end the young republic's longest and coldest winter, but worse was yet to come.

Chapter 10

Obliged to Fly

The announcement of the French alliance with America spurred renewed British efforts to reconcile differences with the Americans. When, however, Lord Carlisle arrived in America with a three-man commission to negotiate with Congress, Henry grew incensed that Congress might end the Revolution short of independence. He warned Richard Henry Lee that Britain “can never be cordial with us. Baffled, defeated, disgraced by her colonies, she will ever meditate revenge. We can find no safety but in her ruin, or at least her extreme humiliation. . . .

“For God's sake, my dear sir,” Henry pleaded with his friend, “quit not the councils of your country until you see us forever disjoined from Great Britain. Excuse my freedom. I know your love to our country, and this is my motive.”

With Henry's warning resounding through the chamber, members of Congress refused even to receiveâlet alone negotiate withâthe British commissioners and declared any individual or group who came to terms with Carlisle's commission an enemy of the United States. The only issues open to discussion with England, Congress asserted, was withdrawal of British troops and American independence. Should Britain “persist in her present career of barbarity, we will take such exemplary vengeance as shall deter others from a like conduct.”

1

1

Lord Carlisle tried bypassing Congress with a “Manifesto and Proclamation to the American People” threatening “to desolate” the country if Americans rejected his offer to negotiate. “Under such circumstances,” Carlisle warned, “the laws of self-preservation must direct the conduct of Great Britain.” Carlisle offered to negotiate with the “Provincial Assemblies” and promised a general pardon to all who ended their rebellion. When an aide to Lord Carlisle delivered the offer of a general pardon to Williamsburg, Henry called it “calculated to mislead and divide the good people of this country” and ordered the aide “to depart this state . . . with the dispatches and to inform him [Lord Carlisle] that, in future, any person making a like attempt shall be secured as an enemy to America.”

2

2

With no confederation yet in place, Henry, as head of a sovereign state, undertook to establish formal diplomatic relations with both France and Spain, appointing one of Richard Henry Lee's brothersâWilliam Leeâas Virginia agent to France. Lee was able to purchase almost V£220,000 in artillery, arms, and ammunition from the French ministry of war using the state's own printed moneyâthe “Virginia pound.” Henry also made an unsuccessful application to the Spanish governor of New Orleans for a loan.

With the western part of the state still under siege, land values in the West plunged, and two of Henry's friends shared an opportunity with him to buy 30,000 acres for V£15,000 in depressed Virginia pounds. In effect, Henry and his partners paid the equivalent of V£3,333 for the lands, with each partner taking outright ownership of his share. Henry's 10,000 acres straddled Leatherwood Creek, a tributary of Smith River, in Henry County, near present-day Martinsville.

On May 29, 1778, Virginia's Assembly reelected him governor for a third term by acclamation, with no other name even placed in nomination. As he had after election to his first term, Henry fell ill after taking the oath of office and remained bedridden for more than a month. Still distraught over the disappearance of his son John after the Battle of Saratoga, Henry sent Washington an emotional letter asking his help in finding the boy. In accord with Henry's request, Washington burned the letter and began a discreet search. Months later, in September 1778, Washington forwarded to Patrick Henry “a letter for Capt. Henry, whose ill state of health obliged him

to quit the service. ...”

3

Shortly afterwards, Dolly assuaged some of Henry's concerns over his son by giving birth to her first and his seventh child, a girl they named Dorotheaâthe first child of a sitting governor to be born in a governor's mansion in America. It was customary to name firstborn girls for their mothers, just as parents named firstborn boys for their fathers.

to quit the service. ...”

3

Shortly afterwards, Dolly assuaged some of Henry's concerns over his son by giving birth to her first and his seventh child, a girl they named Dorotheaâthe first child of a sitting governor to be born in a governor's mansion in America. It was customary to name firstborn girls for their mothers, just as parents named firstborn boys for their fathers.

A month after baby Dorothea's birth, Washington again wrote to Henry that “I was informed (upon further enquiry after him) that he had got no further than Elizabeth town in the Jerseys and was there rather distressed for want of money, having been indisposed at that place for sometime.” Washington said that the commanding officer in Elizabeth “readily understood to furnish what money he wanted and in other respect help him.”

4

John eventually found his way home, and his father lopped off 1,000 acres from his 10,000-acre Leatherwood plantation for the boy to farm on his own, giving him seven of the forty-two slaves at Leatherwood.

4

John eventually found his way home, and his father lopped off 1,000 acres from his 10,000-acre Leatherwood plantation for the boy to farm on his own, giving him seven of the forty-two slaves at Leatherwood.

On June 17, the British declared war on France, and when a French fleet set sail for America with troops to support Patriot forces, the British evacuated Philadelphia to consolidate their forces in New York. On June 18, 3,000 Redcoats boarded ships and sailed down the Delaware River to the Atlantic and the sea route to New York, while the remaining troops began the overland trek northward through New Jersey. With their artillery, military equipment, and baggage train of 1,500 carriages stretching twelve miles, the columns provided just the sort of slow-moving target Washington had been seeking. Instead of direct confrontation, his army could trail the British convoy and harass them with deadly sniping from the sides and rear. He did not believe the Continental Army was large enough or strong enough to defeat the British army in direct, head-to-head confrontations, but he was certain his Americans could weaken and demoralize the British with constant harassment. Attrition and exhaustion, he believed, would eventually force them to abandon the field and sail home to Britain.

With the beginning of the summer campaign, Washington issued his usual call to Congress and states for more men and materiel. He faced constant depletion of his forces because of the short enlistment periodsâoften as little as thirty daysâthat many states had been forced to offer as incentives for army service. Farmers, especially, had to leave the army and

return to their fields in spring and fall to plant and harvest crops to sustain their families. “Public service seems to have taken its flight from Virginia,” Henry lamented to Richard Henry Lee, “for the quota of our troops is not half made up, and no chance seems to remain for completing it.

return to their fields in spring and fall to plant and harvest crops to sustain their families. “Public service seems to have taken its flight from Virginia,” Henry lamented to Richard Henry Lee, “for the quota of our troops is not half made up, and no chance seems to remain for completing it.

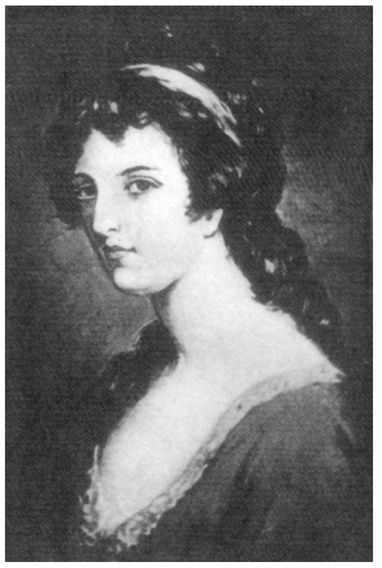

Dorothea Henry, Patrick Henry's first child by his second wife, also named Dorothea and to whom her daughter was said to bear a close resemblance.

(FROM A NINETEENTH-CENTURY PHOTOGRAPH OF A PAINTING)

(FROM A NINETEENTH-CENTURY PHOTOGRAPH OF A PAINTING)

The Assembly voted three hundred and fifty horse and two thousand men to be forthwith raised, and to join the grand [Continental] army. Great bounties are offered, but I fear the only effect will be to expose our state to contempt, for I believe no soldiers will enlist. . . . Let not Congress rely on Virginia for soldiers.

5

5

Even with near-dictatorial powers, Henry found he could not force Virginians to do his bidding and march off to battle. “I ordered fifty men to be raised,” complained one captain to Governor Henry, “only ten appeared.” He said that militia members fail even to appear at musters, saying that “they can afford to pay . . . the trifling fine of five shillings . . . by earning more at home. . . . With such a set of men, it is impossible to render any service to country or county.”

6

6

Most Virginians owned small properties far from the centers of political power. Few expected independence to affect their lives. Almost all believed that the same powerful Tidewater planters who had taxed them before the war as burgesses under British rule had called for independence only to protect their own interests from British taxation, and would reclaim their seats after independence and tax them just as heavily as before.

As the British evacuated Philadelphia, a week of heavy rains combined with searing summer heat and suffocating humidity to slow the huge British convoy to six miles a day. On June 26, the exhausted Redcoats encamped at Monmouth Courthouse (now Freehold), New Jersey, with the Patriots only six miles behind. Two small forces of 1,000 men each had been stalking the British, and Washington ordered a 4,000-man brigade under English-born General Charles Lee to attack the center of the British line from the rear, while the two smaller forces under “Mad” Anthony Wayne and the Marquis de Lafayette sliced into the British flanks. Washington would hold the main army, three miles back. If the attack succeeded, his army would join the battle; if the British proved too powerful, the main army would cover an orderly retreat by the forward brigade. After the attack began, Washington sent his aide Colonel Alexander Hamilton to reconnoiter. To Hamilton's astonishment, Lee's force was retreating in chaos, leaving Lafayette's column trapped behind enemy lines. Outraged at Hamilton's report, Washington galloped into Lee's camp shouting “till the leaves shook on the trees.”

7

7

“You damned poltroon [coward],” he barked at Lee, then ordered him to the rear and took command himself. He galloped into the midst of the retreating troops, shifting his mount to the right, to the left, turning full circle and rearing upâgradually herding the men into line.

“Stand fast, my boys!” he shouted. “The southern troops are advancing to support you!”

8

As Washington's men drove the British back, “Mad” Anthony Wayne lived up to his sobriquet by ordering an insane charge into the British flank that opened the way for Lafayette's men to escape capture. With cannon blasts still blazing overhead, Washington reformed the lines and led a huge frontal attack. Great horseman that he was, he charged heroically atop his huge horse, calling to his men, inspiring them to follow. With a surge of energy, the Continentals repelled a British cavalry charge and sent enemy forces reeling back toward Monmouth Courthouse.

8

As Washington's men drove the British back, “Mad” Anthony Wayne lived up to his sobriquet by ordering an insane charge into the British flank that opened the way for Lafayette's men to escape capture. With cannon blasts still blazing overhead, Washington reformed the lines and led a huge frontal attack. Great horseman that he was, he charged heroically atop his huge horse, calling to his men, inspiring them to follow. With a surge of energy, the Continentals repelled a British cavalry charge and sent enemy forces reeling back toward Monmouth Courthouse.

“General Washington was never greater in battle than in this action,” Lafayette recalled. “His presence stopped the retreat; his strategy secured the victory. His stately appearance on horseback, his calm, his dignified courage . . . provoked a wave of enthusiasm among the troops.”

9

9

Before Washington could seal his victory, darkness set in and ended the day's fighting. As Washington and his exhausted troops slept, the British quietly slipped away to Sandy Hook, a spit of land on the northern New Jersey shore at the entrance to New York Bay. Transports carried them away to New York and deprived the Americans of a clear-cut victory. Although Monmouth was not decisive, the Americans nonetheless claimed victory, with Washington writing to his brother John that Monmouth had “turned out to be a glorious and happy day. . . . ”

10

10

Washington wrote to Henry as if to America's head of state: “I take the earliest opportunity of congratulating you on the success of our arms over the British on the 28th June near Monmouth Court House.”

Other books

Between Two Wolves and a Hard Place by Cassie Wright

The Chalk Circle Man by Fred Vargas

Head Over Heels by Christopher, J.M.

When We Were Sisters by Emilie Richards

What the Groom Wants by Jade Lee

London Bound by Jessica Jarman

Checkmate by Tom Clancy

House of Peine by Sarah-Kate Lynch

Dawn (The Dire Wolves Chronicles Book 3) by Alyssa Rose Ivy

Hotspur by Rita Mae Brown