Authors: Harlow Giles Unger

Lion of Liberty (35 page)

Madison discovered that the publisher of Philadelphia's Antifederalist

Independent Gazetteer

had arrived in Richmond “with letters for the antifederal leaders from New York and probably Philadelphia” and spent time “closeted” with Henry, Mason, and other Antifederalists. Although Madison had no knowledge of it, New York Governor Clinton was in the first stages of uniting New York and Virginia to thwart ratification of the Constitution by linking New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia in a new “middle confederacy.” Henry, meanwhile, had taken a more significant step with an approach to the French minister plenipotentiary to determine how France might react to a declaration of independence by Virginia.

Independent Gazetteer

had arrived in Richmond “with letters for the antifederal leaders from New York and probably Philadelphia” and spent time “closeted” with Henry, Mason, and other Antifederalists. Although Madison had no knowledge of it, New York Governor Clinton was in the first stages of uniting New York and Virginia to thwart ratification of the Constitution by linking New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia in a new “middle confederacy.” Henry, meanwhile, had taken a more significant step with an approach to the French minister plenipotentiary to determine how France might react to a declaration of independence by Virginia.

In a letter to his foreign minister in Paris, the Comte de Moustier reported the plan by “Monsieur Patrick Henri . . . to detach his state from the confederation. If he carries the votes from North Carolina . . . he would be able to form a body strong enough to sustain itself against the efforts of the party opposed to his plan.”

29

29

On June 24, with only five days left for delegates to vote the Constitution up or downâor adjourn without a decisionâHenry came to the hall elated by the support he had built with the Mississippi River issue. He was certain he could now crush Federalist chances for ratification over

an explosive issue no one had yet dared address: the power of the new federal government to decree that “every black man must fight . . . that every black man who would go into the army should be free.” As looks of horror spread across the hall, Henry stared directly at Madison and demanded to know, “May they not pronounce all slaves free?” Without giving the shaken little Federalist leader a chance to respond, Henry roared his own answer, in words that would echo across the South for the next seventy-five years to justify secession:

an explosive issue no one had yet dared address: the power of the new federal government to decree that “every black man must fight . . . that every black man who would go into the army should be free.” As looks of horror spread across the hall, Henry stared directly at Madison and demanded to know, “May they not pronounce all slaves free?” Without giving the shaken little Federalist leader a chance to respond, Henry roared his own answer, in words that would echo across the South for the next seventy-five years to justify secession:

They have the power in clear unequivocal terms and will clearly and certainly exercise it! As much as I deplore slavery, I see that prudence forbids abolition. I deny that the general government ought to set them free, because a decided majority of the States have not the ties of sympathy and fellow-feeling for those whose interests would be affected by their emancipation. The majority of Congress is in the North, and the slaves are to the South. In this situation, I see a great deal of the property of Virginia in jeopardy. . . . I repeat it again, that it would rejoice my very soul that everyone of my fellow beings was emancipated . . . but is it practicable by any human means to liberate them, without producing the most dreadful and ruinous consequences? We ought to possess them, in the manner we inherited them from our ancestors, as their manumission is incompatible with the felicity of our country. . . . This is a local matter and I can see no propriety in subjecting it to Congress.

30

30

As shouts of anger spewed from the gallery, Madison stood to try to refute Henry, but Henry would not be silenced. After proposing a rapid-fire series of amendments, including a bill of rights, his voice rose to a crescendo as he called on God's wrath to punish the authors of the Constitution.

“He [Madison] tells you of important blessings, which he imagines will result to us and mankind in general from the adoption of this system,” Henry thundered. “I see the awful immensity of the dangers with which it is pregnant.

“I see it!

“I feel it!”

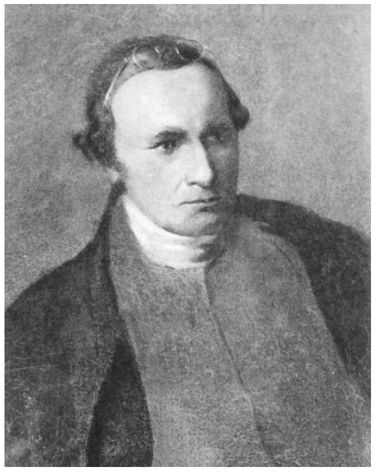

Patrick Henry as Governor of Virginia by unknown artist.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

He spread wide his arms and quaking hands and looked to the heavens, playing the scene like the veteran actor he was. Outside the skies blackened suddenly and turned day into night.

I see

beings

of a higher order

â

anxious concerning our decision. When I see beyond the horizon . . . those intelligent beings which inhabit the ethereal mansions, reviewing the political decisions and revolutions which in the progress of time will happen in America . . . Our own happiness alone is not affected by the event. All nations are interested in the determination. We have it in our power to secure the happiness of one half of the human race. Its adoption may involve the misery of the other hemispheres.

31

beings

of a higher order

â

anxious concerning our decision. When I see beyond the horizon . . . those intelligent beings which inhabit the ethereal mansions, reviewing the political decisions and revolutions which in the progress of time will happen in America . . . Our own happiness alone is not affected by the event. All nations are interested in the determination. We have it in our power to secure the happiness of one half of the human race. Its adoption may involve the misery of the other hemispheres.

31

Lightning struck the ground outside, then an explosion of thunder shook the entire hall. Henry closed his eyes and lifted his face to the heavens, as his ghostly words continued echoing through the chamber:

“

I see it!

I see it!

“I feel it!

”

”

And the heavens responded with another bolt of lightning and jolt of thunder. Terrified delegates fell to their knees or raced to the door. “The spirits he had called seemed to come at his bidding,” cried Federalist delegate Judge Archibald Stuart, “and, rising on the wings of the tempest, he seized upon the artillery of heaven, and directed its fiercest thunders against the heads of his adversaries. The scene became insupportable, and . . . without the formality of adjournment, the members rushed from their seats with precipitation and confusion.”

32

32

The lion of liberty had summoned the very heavens to set men free of government tyranny.

Chapter 15

Beef! Beef! Beef!

When the convention resumed the following morning, some spectators in the gallery returned convinced that Henry had summoned the “black arts” and called down lightning bolts on his antagonists. Black arts or not, he nonetheless failed to win enough votes to block ratification. James Madison had summoned a few black arts of his own by approaching moderate Antifederalists with a pledge to fight for passage of a bill of rights in the First Congress if they switched their votes in favor of ratification. He succeeded in organizing an eighty-nine to seventy-nine vote in favor of ratification, allowing Virginia to become what delegates believed was the decisive ninth state to ratify the Constitution.

Henry won just three of fourteen Kentucky votes, with eleven of the buckskins deciding that a federal army would give them greater protection against Indian attacks and a better chance to seize control of the Mississippi River from Spain. Most delegates agreed that Madison's pledge to champion a bill of rights was the decisive factor in the Federalist victory. Henry had no faith in Madison's pledge, but he learned about it too late to mitigate its effects. Before the convention adjourned, Madison urged Federalists to try to heal the wounds of discord by supporting Antifederalist proposals to recommend forty amendments to the Constitution, including

a bill of rights, “to the consideration of the Congress which should first assemble under the Constitution.”

1

a bill of rights, “to the consideration of the Congress which should first assemble under the Constitution.”

1

Although Washington never set foot in the convention hall, Federalists and Antifederalists agreed that he, rather than Henry, had dominated the exhausting drama. Indeed, Henry seemed at times to be debating Washington rather than Madison, Randolph and the other Federalists in the convention hall. Delegates sensed Washington's presence in every utterance, and, knowing he was the nation's all but unanimous choice for president, he exerted his political power behind the scenes by neutralizing two of Virginia's most influential political leaders: former governor Thomas Jefferson and the state's sitting governor Edmund Randolph. A year after the critical Virginia convention, Washington, by then the nation's chief executive, would confirm Henry's suspicions by appointing Jefferson the nation's first secretary of state and Randolph the first attorney general.

“Be assured,” James Monroe declared, “General Washington's influence carried this government.”

2

Antifederalist William Grayson concurred. “I think that, were it not for one great character in America,” he growled in his closing argument, “so many men would not be for this Government. . . . We have one ray of hope. We do not fear while he lives, but we can only expect his

fame

to be immortal. We wish to know, who besides him can concentrate the confidence and affections of all America.”

3

2

Antifederalist William Grayson concurred. “I think that, were it not for one great character in America,” he growled in his closing argument, “so many men would not be for this Government. . . . We have one ray of hope. We do not fear while he lives, but we can only expect his

fame

to be immortal. We wish to know, who besides him can concentrate the confidence and affections of all America.”

3

After the vote, all eyes turned to Henry. Many feared he would rise from his seat and cry for vengeance as in 1775: “We must fight!” Some buckskins in the gallery were ready to cock their rifles. Seeing the looks of fear on the faces of some delegates, Henry acted to calm the situation and forestall civil disobedience, but he nonetheless vowed to continue his struggle for a bill of rights.

If I shall be in the minority, I shall have those painful sensations which arise from a conviction of being overpowered in a good cause. Yet I will be a peaceable citizen! My head, my hand, my heart shall be at liberty to retrieve the loss of liberty and remove the defects of that systemâin a constitutional way. I wish not to go to violence, but will wait with hopes that the spirit which predominated in the revolution is not yet gone, nor the cause of those who are attached to the revolution yet lost. I

shall therefore patiently wait in expectation of seeing that Government changed so as to be compatible with the safety, liberty and happiness of the people.

4

shall therefore patiently wait in expectation of seeing that Government changed so as to be compatible with the safety, liberty and happiness of the people.

4

By the time transcripts of his address reached the nation's newspapers, enough words and phrases, such as “in a constitutional way,” had been smudged or omitted to produce a revolutionary manifestoâespecially when paired with the statements of Henry's confederates. Mason, Monroe, and their “Federal Republicans” had been far less conciliatory than Henry after the ratification convention. They had stormed out of the hall, intent on continuing the fight, gathering at a nearby tavern, and sending for Henry to propose ways to reverse the convention result. Although Henry had suffered a humiliating defeat at the convention, Virginia's farmers and frontiersmen still looked to him to defend their rights.

After calming the angry gathering, he proposed various schemes for reversing the effects of ratification “in a constitutional way.” First and foremost, he would try to prevent the remaining four states from ratifying. At the same time, he would call on state legislatures that had ratified to call a second constitutional convention to undo the work of the first convention and prevent a new government from taking office. If, however, the states rejected the idea of another convention and the new Constitution took effect, Antifederalists had other weapons at their disposal to undo the Constitution: They could use their popular majority to elect an Antifederalist majority to the new congress and, once installed, they could propose constitutional amendments to guarantee individual rights and states' rights and to dilute the powers of the new government.

When Madison learned of the meeting, he reported to Washington that “although Henry and Mason will give no countenance to popular violence, it is not to be inferred that they are reconciled to the event.” He warned that Henry planned to work for the election of a Congress “that will commit suicide on their own authority.”

5

5

After Virginia's ratification convention, jubilant Federalists spent two days of raucous, self-congratulatory celebrations before learning that theirs had not been the decisive ninth state to ratify. New Hampshire had reconvened its convention and ratified four days before Virginia, on June 21.

With Virginia's ratification, however, New York's Antifederalist Governor George Clinton recognized the futility of continuing his own struggle. Although an independent and sovereign New York might have presented physical obstacles to overland trade between New England and the rest of the Union, traders could easily bypass New York harbor over a sea link between Philadelphia and Bostonâvia a canal then under consideration across the base of Cape Cod at Buzzard's Bay. On July 26, 1788, New York ratified and became the eleventh state in the Union.

In the end, Patrick Henry and his Antifederalists scored their only success in North Carolina, where an overwhelming majority of delegates at the ratification convention voted against ratification. Like Henry's own Piedmont area, North Carolina was almost entirely rural, sparsely populated by relatively poor, but fiercely independent, farmers and frontiersmen who resented government intrusions in their lives and had been unrepresented at the Constitutional Convention. Desperate to secure at least one political base, Henry's acolytes warned that wealthy big-city merchants and bankers were plotting to control the country. Willie Jones, the state's political boss, pleaded with the ratification convention to keep North Carolina out of the Union until it could negotiate more advantageous terms for joining. Jones read the letter from Thomas Jefferson, declaring, “Were I in America, I would advocate it warmly till nine should have adopted it and then as warmly take the other side to convince the other four that they ought not to come into it till the declaration of rights is annexed to it.”

6

On August 2, North Carolina voted to defer ratification 184 to 84.

6

On August 2, North Carolina voted to defer ratification 184 to 84.

Other books

Listen To Me Honey by Risner, Fay

The Vow by Fallon, Georgia

The Hornet's Sting by Mark Ryan

Bruach Blend by Lillian Beckwith

Lorraine Bartlett - Tori Cannon-Kathy Grant 00.5 - Panty Raid by Lorraine Bartlett

Roman Dusk by Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

Hauntings and Heists by Dan Poblocki

The Turning Point by Marie Meyer

Analog SFF, September 2010 by Dell Magazine Authors

Devouring The Dead (Book 2): Nemesis by Watts, Russ