Listening In (14 page)

Authors: Ted Widmer

JFK:

Or second-guessers.

[break]

JFK:

[Yeah?]

MACARTHUR:

This talk about the Republican Party taking the House is a lot of [hocus bull?]. They’ve got no more chance of taking the House than I have of flying over this house.

[break]

JFK:

Yeah, yeah. Do you know this fellow Romney? Have you met Romney? George Romney?

23

MACARTHUR:

Only casually.

JFK:

Yeah, yeah.

MACARTHUR:

He doesn’t stand a chance.

JFK:

What do you think, Rockefeller? You think he has …

MACARTHUR:

He’s a very presentable man, personally, he would fill the bill. He looks it and everything. But he … to begin with, Mr. President, he’s practically unknown. I tried it out. I talked with one hundred people the other day, just as I happened to meet them. The bellhops. They would be window cleaners [?]. They were the maids. They were the servants. They were my own board of directors, and others. And of those hundred people, with the exception of the board of directors, there were only two that knew who Romney was.

JFK:

[Yeah?]

MACARTHUR:

You can’t pick the president that way. Now I know this piece came out yesterday, according to the

New York Times

, which is not always reliable.

JFK:

[laughs]

MACARTHUR:

And said he wasn’t going to run in ’64.

JFK:

Yeah, I heard those statements.

MACARTHUR:

Well, he [laughs], it was a pretty smart move, because even if he got the nomination, he couldn’t win it. And he’d have to build himself up as the governor of Michigan and make a campaign from the bottom up. No, don’t worry about these smart-aleck columnists that have to write something. It’s their bread and butter, you know. And the easiest thing is to get the big figure and damn him. I remember listening to old Mr. Hearst once. William Randolph Hearst.

24

And he was talking to a group of young reporters that he had just assembled. And at that time, he was at the height of his journalistic empire. And he said, “Now,” he said, “the best way, the main purpose of my papers,” he says, “is to sell them.” And he says, “Dry and dull papers,” he says, “never make the grade.” Now, he says, “When you don’t get something sensational,” he says, “make it.” And some little fellow says, “Well, Mr. Hearst, how do you make it?” Well, he says, pick out the finest, the most honest, the most prominent man in your society, and attack him [physically and—?]

JFK:

[laughs]

MACARTHUR:

He says, “He’ll deny it,” he says, “and then you’ll have the sensation.”

JFK:

Yeah. Then you’ll have it.

MACARTHUR:

And there are a great many of these horrors. They’d rise up and vehemently deny, but a great many of them do that. Their stock in trade is a tirade against the great.

MEETING WITH PRESIDENT DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER, SEPTEMBER 10, 1962

John F. Kennedy was an unlikely successor to Dwight D. Eisenhower. The former supreme commander of the Allied Forces in Europe took a while to warm up to the former navy lieutenant, twenty-seven years his junior, whom he called “that young whippersnapper.” Kennedy had not met with Eisenhower once during his eight-year presidency, and during the 1960 campaign he freely criticized his complacent leadership. But that surface chilliness concealed a genuine respect that only grew as they began to know each other as fellow presidents. Kennedy drew upon Eisenhower’s military and political wisdom on numerous occasions, particularly during the Cuban Missile Crisis. This conversation, in the aftermath of the crisis, included some shared exasperation at the daily price paid for being France’s ally; reflections on the Cold War and its flash point, Berlin; and Ike’s memories of early tensions with the Russians in the waning days of World War II.

EISENHOWER:

Well, of course, on that one, Mr. President, I’ve personally, I’ve always thought this from the beginning. If they believe there is no amount of strength you can put in Berlin, they can say that. I would think that you could … What’s his name, Khrushchev,

25

said to me at Camp David, he was talking about [the United States] needing some more troops [in West Germany], there was somewhat at that time in the public about more, a couple more divisions, and so … he says, “What are they talking about?” He says, “For every division they can put in Germany, I can put ten, without any trouble whatsoever.”

And I said, “We know that.” And I said, “But we’re not worrying about that.” And I said, “I’ll tell you, I don’t propose to fight a conventional war.” If you declare, if you bring out war, bring on a war of global character, there are going to be no conventional, nothing conventional about it.” And I told him flatly. And he said, “Well.” He said, “That’s a relief. Neither one of us can afford it.” “Yes,” I said that, and I said, “OK, so I agree to that, too.” [laughter]

JFK:

Right, right.

PRESIDENTS KENNEDY AND EISENHOWER, SEPTEMBER 10, 1962

EISENHOWER:

But you see, what these people are afraid of, I mean the essence of his argument was, if you try to fight this thing conventionally from the beginning, when do you start to go nuclear? And this will never be until you yourselves in other words become in danger and he said, “That means all of Europe is again gone.” And that …

JFK:

But of course, we’ve got all these nuclear weapons, as you know, stored in West Berlin. All we are … what they are really concerned about is that the Russians will seize Hamburg, which is only a few miles from the border, and some other towns, and then they’ll say, “We’ll negotiate.” So then Norstad

26

has come up with this whole strategy. I think the only difficulty is that no one will … that if we did not have the problem, as I say, of Berlin and maintaining access through that autobahn authority, then you would say that any attempt to seize any part of West Germany, we would go to nuclear weapons. But of course, they never will. But it’s this difficulty of maintaining a position 120 miles behind their lines.

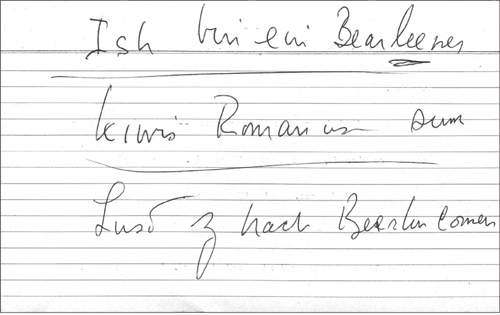

PRESIDENT KENNEDY ADDRESSES THE PEOPLE OF WEST BERLIN, RUDOLPH WILDE PLATZ, JUNE 26, 1963

Ish bin ein Bearleener (Ich bin ein Berliner/I am a Berliner),

kiwis Romanus sum (civis Romanus sum/I am a Roman citizen),

Lust z nach Bearlin comen (Lass’ sie nach Berlin kommen/Let them come to Berlin)

PRESIDENT KENNEDY’S SPEECH CARD FROM BERLIN, SPELLED PHONETICALLY TO IMPROVE HIS PRONUNCIATION OF GERMAN AND LATIN WORDS

EISENHOWER:

Mr. President, I’ll tell you, here’s something. I can’t document everything. But Clay

27

was there. Poor, poor old Smith

28

is gone. We begged our governments not to go into Berlin. We … I asked that they build a cantonment capital, a cantonment capital at the junction of the British, American, and Russian zones. I said, “We just don’t, we can’t do this.” Well, it had been a political thing that had been done first in the advisory council, European Advisory Council, in London. And later confirmed and … but Mr. Roosevelt said to me this twice—I’m talking about my concern. And he said, “Ike,”—and he was always very, you know, informal—he said, “Ike,” he said, “quit worrying about Uncle Joe. I’ll take care of Uncle Joe.”

29

That’s exactly what he told [me]. Once in Tunis and once when I came over here about the first or second or third of January of ’44. That’s the last time I ever saw him. Now he just wouldn’t believe that these guys were these tough and really ruthless so-and-sos they were.