Living by the Book/Living by the Book Workbook Set (38 page)

Read Living by the Book/Living by the Book Workbook Set Online

Authors: Howard G. Hendricks,William D. Hendricks

Tags: #Religion, #Christian Life, #Spiritual Growth, #Biblical Reference, #General

B

y now you should have looked at the content and the context of Daniel 1–2. Are you beginning to get some sense of what’s going on in this story? What questions do you have as a result of your study?

Perhaps you’ll answer some of them by doing a little comparison of this text with other portions of Scripture. Using a concordance, look up the following four items, each of which is crucial to understanding the passage. See how much you can learn about them from other places in Scripture:

• Daniel

• Nebuchadnezzar

• Babylon

• dreams

HE

C

OW

I

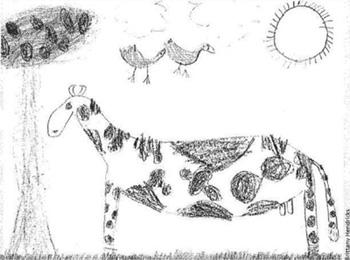

ran across a touching essay by a ten-year-old pupil. It has some correct observation, but incorrect interpretation. It also has some correct interpretation, with incorrect observation. Here’s what the child wrote:

The cow is a mammal. It has six sides. Right, left, an upper and below. At the back it has a tail on which hangs a brush. With this it sends the flies away so that they do not fall into the milk. The head is for the purpose of growing horns and so that the mouth can be somewhere. The horns are to butt with and the mouth is to moo with. Under the cow hangs the milk. It is arranged for milking. When people milk the milk comes and there is never an end to the supply. How the cow does it I have not yet realized. But it makes more and more. The man cow is called an ox. It is not a mammal. The cow does not each much, but what it eats, it eats twice so that it gets enough. When it is hungry it moos, and when it says nothing it is because its inside is all filled up with grass.

As you can see, we need to be very precise in how we go about this process of interpretation. We must make sure our observations are accurate so that we have a basis for accurate interpretation.

ULTURE

I

was once the guest of a man who lived in San Francisco. He was an importer of exquisite Oriental lace. One evening as we were leaving his house, a little end table in the vestibule by the front door caught my eye. What attracted me was not the table but a piece of lace lying on it.

I said, “My, that’s beautiful.”

My host grimaced. “That’s a piece of junk,” he said.“I keep telling my wife to take that thing out of here.”

Surprised, I asked him, “How can you tell good lace from junk?”

He winked and said, “When we get back, I’ll show you.”

Believe me, I didn’t forget. So when we returned he took me into a room with a large black table that had a brilliant light over it. He threw a massive piece of oriental lace over the table, and proceeded to give me a lesson in how to tell the difference between fine lace and junk material. In the process, he commented, “You’ll never understand the exquisiteness of good lace until you see it against a dark background with bright light shining on it.”

Later I thought,

That’s a clue to studying the Bible

. You have to see it against the right background, with the right light shining on it, to capture its

meaning. In

chapter 31

we saw the importance of context in terms of the text of Scripture—paying attention to what comes before and what comes after the passage you are studying. In the same way, you have to pay attention to the cultural and historical context—to the factors that led to the writing of the passage, the influences they had on the text, and what happened as a result of the message. That’s the fourth key in making accurate interpretation of the Scriptures:

ULTURE

Let me illustrate what I mean by the cultural context with several examples.

The Old Testament book of Ruth is a beautiful story of love and courage. But most people overlook the fact that it takes place during the period of the judges, Israel’s Dark Ages. That’s because they fail to observe Judges 21:25, which sets up the context for Ruth 1:1. It shows that the nation was mired in a cesspool of iniquity. It was a time in the culture when they couldn’t tell the difference between Chanel No. 5 and Sewer Gas No. 9. Reading the account, you have to wonder, was anyone faithful to God during this period?

Answer? Look in the book of Ruth. It’s a shaft of light in the midst of a dark period. It’s a brilliant lily in a putrid pond. Here’s a dear family, faithful to Jehovah, even in the midst of apostasy.

And yet I’ve heard people make snide remarks about the book of Ruth because of an incident in the story involving Ruth spending the night at the feet of a man named Boaz. One guy even said to me with a snicker, “Hey, that’s kind of a saucy book, isn’t it? A little sexy.”

I thought,

My friend, that’s a greater commentary on you than it is on the book of Ruth.

You see, that fellow was tipping his hand. He was showing me that he didn’t know the front end from the back end of the culture in which Ruth took place. When you go back and study the customs involved, you discover that in context they are of the highest moral standard. Nothing cheap about them. This is no trashy novel you are reading. It’s the highest form of literature, both in terms of content and morality.

But here as elsewhere, we read the Bible according to our own culture, as through a pair of glasses that distorts the context. No wonder we can’t make sense of the passage.

A classic illustration of the tendency to interpret Scripture according to one’s own culture is Leonardo da Vinci’s masterpiece,

The Last Supper

(see

p. 243

). It’s an incredible work of art, no doubt. Yet that would not be the place to go if you wanted to find out what the actual Last Supper was really like. The painting portrays a rather different picture of the setting—namely, a fifteenth-century interpretation of it.

In the first place, Leonardo has Jesus and His disciples sitting at a table. But people didn’t sit at tables to eat in the time of Christ; they reclined. They lay on couch-like furniture, leaning on an elbow, which left the other hand free to eat. That’s important, because remember that Peter asked John, “Who is Jesus talking about when He says that one of us is going to betray Him?” (John 13:24). The rest of the disciples could not hear Peter. Why? Because he was able to lean back, John could come forward, and the two could communicate.

Leonardo also has them all seated on the same side of the table, as at a speaker’s table. It’s a carefully organized arrangement, as if someone had said, “Hey guys, let’s all gather around and take a company picture. One last shot before the Lord goes.” But of course, in reading the account you realize that that was not the seating involved.

Another interesting feature of

The Last Supper

is that Leonardo has painted a fifteenth-century frieze on the back wall. That obviously reflects Leonardo’s time, not the first century. And if you observe carefully, you’ll notice that in Leonardo’s painting, it is daylight outside. But according to the biblical account, the actual Last Supper took place in the evening, and probably well into the night.

Now don’t misunderstand. As a painting,

The Last Supper

has great value. But the unfortunate thing is that by looking at a beautiful piece of art, people often get a rather flawed interpretation of a passage of Scripture. (Actually, if they knew better how to look at art, they would gain insight into the situation. That’s one of the marks of good art.) Accuracy demands that one go

back to the original period and culture to find out what was really going on. Indeed, unless you understand the original context of the Last Supper, you can’t fully appreciate Leonardo’s masterpiece.