Long Time No See (13 page)

Authors: Ed McBain

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #United States, #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Hard-Boiled, #Series, #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Police Procedurals

A pair of ambulance attendants lifted the body onto the stretcher. One of them started to throw a rubber sheet over it. Carella identified himself and told them to wait a minute, he wanted to have a look at her.

“We been told to remove her from the premises,” one of the attendants said.

“Right, and I’m asking you to hold a minute, okay?” Carella said.

“It’s the ME says when to take a stiff or when not to take it,” the attendant said. “Anyway, who are you? Are you the investigating officer here? I thought the

other

guy was the investigating officer.”

Carella didn’t answer him. He was stooping beside the body, looking into the dead woman’s face as though trying to read the identity of the murderer there. The neck wound was gaping and raw; he turned away. Her hands had been put in plastic bags, par for the course when the weapon was a knife and the attack proximate. No dutiful ME would have neglected the possibility that the victim may have scratched out in self-defense and might be carrying under her fingernails samples of the murderer’s skin or blood.

“All right, you can take her,” Carella said.

“You dope it out yet?” the attendant asked sarcastically. “You figured who done it?”

Carella rose from where he’d been kneeling beside the body. He did not say a word. He looked directly into the attendant’s eyes. The attendant visibly flinched, and then bent silently to cover the corpse with the rubber sheet. Silently, he and his partner picked up the stretcher and carried it down the stairs.

“You Carella?” a voice said behind him.

Carella turned. The man was a detective, his shield pinned to the pocket of his tweed overcoat. Fleshy, thickset man with blue eyes and blond hair. Smoking a cigar. Stunk up the hallway with the stench of it.

“Tauber?” Carella asked.

“Yeah,” Tauber said. “You got here, huh?”

“I got here.”

The men did not shake hands. Law-enforcement officers rarely shook hands with each other. Even at dances thrown by the Policemen’s Benevolent Association or the Emerald Society, they did not shake hands. It was a peculiar occupational quirk, Carella thought. In days of yore, knights used to shake hands to make certain the haft of a dagger was not concealed in a closed fist, the blade hidden along the arm. Maybe cops had no daggers to hide.

“Did you see her?” Tauber asked.

“I got a look at her, yes.”

“Policewoman searched her a little while ago. I’ve got her stuff waiting to go to the property clerk, I wanted you to see it first. You know a Homicide cop named Young?”

“No.”

“He’s the one told me you could take charge here if it looks like we got the same killer. I realize a slit throat’s a slit throat. But if I remember your stop-sheet, both victims were blind, and nothing was stolen, am I right?”

“That’s right.”

“Well, the lady had twenty-two dollars and fifty cents in her handbag, and she was wearing a gold crucifix around her neck, and also a gold ring with a small diamond on her right hand. Whoever killed her didn’t take the money or the jewelry, left a good accordion, too—it’s over there against the wall, I already had it tagged, got to be worth a couple of hundred, don’t you think? So robbery wasn’t the motive here. All I’m saying is it looks like a similar m.o. to me.”

“Yes, it does,” Carella said.

“I’m not trying to duck out of this,” Tauber said, “believe me. I got a full caseload right now, but what the hell, one more or less ain’t going to break me. It’s just I really think this might be yours.”

“I understand that. Who found the body?”

“Guy down the hall. I only asked him a few questions, you’ll want to talk to him some more if you’ll be takin’ this over. What do you think? Do you think you’ll be takin’ this over?”

“I guess so,” Carella said.

“Do you want me to hang around, or what?”

“How do we work the paper on this?”

“I guess I file with Homicide, I don’t know. I got Young’s verbal okay, that should be enough, don’t you think?”

“Maybe, I don’t know.”

“I’ll tell you what I’ll do. When I get back to the station house, I’ll give Homicide a call, find out how they want us to handle the paper, okay? If you want to ring me later, I’ll tell you what they suggest. What I think personally is you just handle it like it’s your squeal.”

“All the way downtown here?”

“On the basis of your stop-sheet,” Tauber said, and shrugged. “You asked for dope on a pair of Unusual Crimes, right? Well, now you got another homicide looks related. You ask me, that’s enough.”

“You think the stop-sheet would cover it, huh?”

“That’s my opinion.”

“I just don’t want to get involved in a bunch of departmental bullshit,” Carella said. “That’s the one thing I don’t need on a homicide.”

“Naw, don’t worry.”

“For example, what do we do with her valuables? Does the Eight-Seven’s property clerk get them, or do I send them over to Midtown East?”

“I think your man gets them.”

“That’s what I think,” Carella said.

“That’s what I think, too.”

“Where’s the stuff?”

“There wasn’t much, aside from the cash and the jewelry,” Tauber said. “I got it bagged there against the wall, you want to take a look at it.” He led Carella to where the woman’s accordion was resting against the wall alongside a brown paper bag. The accordion was tagged, and so was the bag. Carella picked up the bag and peeked into it.

“Okay to touch this stuff?” he asked.

“It’s your case,” Tauber said, and shrugged.

“I mean, have the lab boys gone over it?”

“Only the stuff might’ve had latents. The wallet there, and the hairbrush and the address book. The book’s in Braille, it ain’t going to help you much.”

“But it’s okay to have a look at it, huh?”

“Yeah, go ahead. They dusted it already.”

Carella reached into the bag and took out the address book. The book was, in actuality, a small black loose-leaf binder, some three inches in width, five inches in overall length. The pages inside were unlined, most of them punched with a series of dots. Top line, middle line, bottom line, space, and then another line. Carella assumed these constituted the name, address, and telephone number for each listing.

“I wonder how they do that,” Tauber said. “Blind people.”

“They probably have some kind of instrument they use,” Carella said.

“Yeah, probably.”

“Do you think there’s anybody in the department who can translate this stuff?”

“You’ll probably have to go to Languages and Codes,” Tauber said.

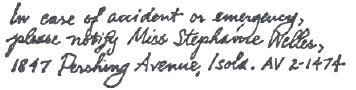

“Here’s something,” Carella said. He had turned to the inside back cover of the book. Pasted to it was a message in somewhat shaky longhand:

“Guess she figured—”

“Yeah,” Carella said.

“She had to write it in longhand, otherwise—”

“Yeah.”

“But it won’t do you no good, anyway,” Tauber said. “The address is an old one. She moved to Chicago six months ago.”

“Where in Chicago?”

“Someplace on Warrington Avenue.”

“Who is she?”

“The woman’s niece.”

“Any other relatives?”

“Not that I know of.”

“She should be contacted,” Carella said.

“You can check the apartment for letters soon as the lab boys are through. You might find an address.”

Before World War I, Pershing Avenue used to be called Grant Avenue. Architecturally, the wide esplanade looked much as it did then. A central divider planted with forsythia bushes and maple trees, leafless now in mid-November. Huge buildings on either side of the avenue, granite cornerstones, limestone facades. Spacious entry courts with concrete flowerpots sitting atop brick pedestals. In the days before World War I, the buildings lining Grant Avenue constituted some of the city’s choicest real estate. They were now scribbled over with graffiti advertising the name of this or that street gang member. The graffiti was over-sprayed—Spider 19 giving way to Dagger 21, in turn giving way to Salazar IV, so that

nobody’s

name meant a rat’s ass any more.

Maybe Spider 19 felt the same way Grant in heaven must have felt when they changed the name of the avenue to Pershing. Pershing himself had narrowly missed having the name changed again to Kennedy shortly after the assassination, when even lampposts were being named after the late president. Up there in heaven, old John Joseph, for such was the general’s name, most likely began muttering about

sic transit gloria mundi

and the high cost of changing street signs. But someone had the good sense to recognize that Roosevelt Street, some three blocks away from Pershing Avenue, had already had

its

name changed to Kennedy Street and another name-change of yet another thoroughfare might prove confusing to pedestrians and motorists alike. The people along Pershing Avenue were grateful. None of them knew General Pershing from a hole in the wall, and none of them would ever forget that bleak assassination day in November as long as they lived, so they didn’t need street names changed, they didn’t need that bullshit at all.

Carella parked his car two blocks from 1847 Pershing, the closest spot he could find, and began walking against the wind blowing through the naked chestnut trees. He had searched Hester Mathieson’s apartment for any back correspondence from Stephanie Welles and had found none; he guessed there was no reason for a blind woman to have saved letters that had to be read to her aloud. He had then called the post office serving the Pershing Avenue area to ask about a forwarding address that might have been filed six months ago, and the night clerk who answered the phone told him he’d have to call back in the morning, the only people there right now were sorting mail and moving it out. He then checked the address in Hester’s book against the Isola telephone directory and came up with an identical listing for Stephanie Welles. The possibility existed that she had sublet the apartment to someone she knew; Carella dialed the number. He let it ring twelve times, and then hung up.

It was 10:00

P.M.

by then.

Tauber had left the scene some forty minutes earlier, promising to check Homicide in an attempt to learn how the transfer to the Eight-Seven should be handled. When Carella called him at five past the hour, Tauber said he had spoken again to Young, and the Homicide cop would be sending out written authorization to the commanding officers at both Midtown East and the Eight-Seven, so that was that. He wished Carella luck with the case. Carella wanted to get a line on Stephanie Welles

now

, tonight, before

this

one began to get cold, too. He drove to Pershing Boulevard hoping for one of two things: either the person who’d rented the apartment after her knew where Stephanie Welles was now living in Chicago, or else Stephanie had left a forwarding address with the superintendent of the building. He was less interested in notifying her of her aunt’s death than he was in soliciting information from her. He did not know how much she knew about the dead woman’s habits or acquaintances, but she’d been listed as the person to call in case of an emergency or an accident, and Hester Mathieson had suffered the biggest accident of them all.

He walked with his head ducked.

The wind was shrill.

He saw the graffiti-marked buildings, and tried to understand—but could not.

His grandfather had come to America from Italy because he’d been told the streets here were paved with gold. They were not, of course, and Giovanni Carella learned that almost at once, driving a horse and wagon for the milk company, the horse dropping the only golden nuggets anywhere in view. Nor were the streets as clean as those to be found in Giovanni’s native Naples, or so Giovanni claimed, a premise perhaps disputable. But in those days, when Carella’s grandfather first got here at the turn of the century, the European sense of tradition and of place caused immigrants like himself to look upon even their slum dwellings as something to be cared for with pride. The buildings—your own building and the building next door and the one next door to that—were

home.

Together they formed “

la vicinanza

,” and you did not defile your home, you did not shit where you ate. No one would have dreamt of scribbling upon the face of a tenement, however grim the building was. No one would have marked a trolley car—the subways were in the process of being built, there

were

no subway cars to mark—because these were people who had lived with beauty centuries old, and they were not yet used to the fact that in America things existed only to be changed or destroyed.

Carella climbed the flat wide steps of the front stoop, past a pair of empty concrete urns, each scribbled over with undecipherable names. He moved across the courtyard toward the entrance doors of the building. Two young boys were playing boxball in the illuminated courtyard. They looked up at him as he went past, and then went back to their game. He entered the outer lobby of the building, and was searching the mailboxes for the super’s apartment number when he came across the names.

WELLES

in the slot under the mailbox for apartment 54. He didn’t know exactly what this meant. Had Stephanie Welles kept the apartment here in Isola while living in Chicago? Or had it been sublet or otherwise rented to someone who’d simply neglected to change the name in the box?