Long Time No See (20 page)

Authors: Ed McBain

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #United States, #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Hard-Boiled, #Series, #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Police Procedurals

“This is Detective Carella, 87th Squad, Isola,” he said. “I have a packet here from Captain McCormick at Fort Jefferson…”

“Yes, Mr. Carella?”

“And I need some further information.”

“Just one moment, sir, I’ll put you through to Mr. O’Neill.”

“Thank you,” Carella said.

He waited.

“O’Neill,” a man’s voice said.

“Mr. O’Neill, this is Detective Carella, 87th Squad, Isola. I have a packet here from Captain McCormick at Fort Jefferson, and I need some further information.”

“What sort of information?” O’Neill asked.

“I’m investigating a homicide in which the victim was a man named James Harris, served with the Army ten years ago, D Company, Second Battalion…”

“Let me take this down,” O’Neill said. “D Company, Second Battalion…”

“Twenty-seventh Infantry,” Carella said. “Second Brigade of the Twenty-fifth Infantry Division. I don’t have a platoon number. He was in Alpha Fire Team of the Second Squad.”

“Rank?”

“Pfc.”

“Service number?”

“Just a second,” Carella said, and consulted Jimmy’s file. He found the number and read off the eight digits slowly. O’Neill would later be feeding this into a computer, and Carella didn’t want any errors.

“Discharged or deceased?” O’Neill asked.

“Both,” Carella said.

“How’s that possible?”

“He was discharged ten years ago and killed last Thursday night.”

“Oh. Oh, I see. I meant…What I meant, we have the records here for anyone who was either discharged or killed in action. The Department of the Army would have the records on anyone retired from the service, or with the reserve. This man was discharged, you said?”

“Yes.”

“Honorable discharge?”

“Yes. Full disability pension.”

“He was wounded?”

“Yes.”

“When?”

“December fourteenth, ten years ago next month.”

“Okay,” O’Neill said, “what is it you want to know?”

“The names of the other men in his fire team.”

“On the date you just gave me?”

“Yes.”

“That might be possible,” O’Neill said. “Depends on who filed the action report.”

“Who normally files it?”

“The OIC. Or sometimes the—”

“Would that be the officer in command?”

“Yes, or sometimes the noncommissioned officer in command. There’s usually a second lieutenant in charge of a platoon, and an E-Seven assisting him. If neither of those two witnessed the particular action that day, then the squad leader may have filed the action report, or even the E-Five leading the fire team. Do you understand how this is broken down?”

“Not exactly,” Carella said. “In my day the squad was the basic unit.”

“Well, it still is, but now the squad’s broken down into two fire teams, Alpha and Bravo. You’ve got five men in each team, with an E-Six leading the full squad, for a total of eleven men. The way each fire team breaks down, there are two automatic riflemen who are Spec Fours or E-Threes, a grenadier who’s usually an E-Four, two riflemen who are E-Threes, and an E-Five leading them.”

“I don’t know what all those numbers mean,” Carella said. “Spec Fours, E-Threes…”

“Those are designations of rank. An E-Three is a Pfc, a Spec Four is a specialist fourth class, a corporal. An E-Five is a three-striper, and so on.”

“Mm-huh,” Carella said.

“What I’m suggesting is that the action report may possibly list the men who were in Harris’s fire team.”

“Would that be in his personal file?”

“Yes,” O’Neill said.

“Well, I’ve got his file right here, and the action report doesn’t mention any other men in the fire team.”

“Who signed the report?”

“Just a minute,” Carella said, and dug through the sheaf of papers again. “A man named Lieutenant John Francis Tataglia.”

“That would’ve been his platoon commander,” O’Neill said. “That’s his Field 201-File you’ve got there, huh?”

“Yes.”

“And the action report doesn’t name the men in his fire team, huh?”

“No.”

“Would there be what we call a Special Order in his file?”

“What’s that?”

“It’s an order assigning a man to such and such a squad, and sometimes it’ll list the other men in the squad by name, rank and service number.”

“No, I didn’t run across anything like that”

“Well then, I guess we’ll have to cross-check with Organizational Records. That may take a little while,” O’Neill said. “May I have your number, please?”

“Frederick 7-8024.”

“That’s in Isola, right?”

“Yes, the area code here—”

“I have it. What was your name again, please?”

“Detective Second/Grade Stephen Louis Carella.”

“You’re with a local law-enforcement agency, am I right?”

“Yes.”

“I’ll get back to you,” O’Neill said, and hung up.

He did not get back till close to 11:00

A.M.

Carella had gone down the hall to Clerical for a cup of coffee, and was just returning to his desk when the telephone rang. He put down the paper carton and picked up the receiver.

“87th Squad, Carella,” he said.

“Harry O’Neill here in St. Louis. I’m sorry, but I didn’t get a chance to run this through the computer till a few minutes ago. I’ve got the company roster here—that’s a long sheet that lists all the men in a company and breaks the company down into four platoons, listing the men alphabetically and by rank. James Harris was in D Company’s Third Platoon. Now…Depending on the morning reports of each platoon, you’ll sometimes get a breakdown of the squads and fire teams in those squads. The clerks in the Third Platoon kept very nice records. I’ve got those names you wanted.”

“Good,” Carella said, “let me have them, please.”

“Got a pencil?”

“Shoot.”

“Rudy Tanner, Pfc, automatic rifleman. That’s T-a-n-n-e-r.”

“Got it.”

“Karl Fiersen, E-Four, grenadier.”

“Carl with a C?”

“With a K.”

“Would you spell the last name for me, please?”

“F-i-e-r-s-e-n.”

“Go on.”

“James Harris and Russell Poole, both Pfc’s, riflemen. That’s Russell with two esses and two els, and Poole with an e.”

“Okay.”

“The sergeant leading the team was an E-Five named Robert Hopewell, just the way it sounds.”

“Right,” Carella said.

“Did you want the names of the platoon commander and his assistant?”

“If you’ve got them.”

“Commander was a man named Lieutenant Roger Blake, later killed in action. The next one’s a tough one, I’d better spell it. Sergeant John Tataglia, that’s T-a-t-a-g-l-i-a.”

“Are you sure about that?”

“About what?”

“Tataglia’s rank. Isn’t he the lieutenant who signed the action report? Just a second,” Carella said, and spread the sheaf of papers on his desk. “Yes, here it is, Lieutenant John Francis Tataglia.”

“Well, he’s listed as a sergeant on this.”

“On what?”

“The platoon’s morning report.”

“Any date on it.”

“December third.”

“The action report is dated December fifteenth.”

“Well, one or the other must be wrong,” O’Neill said. “Unless he was promoted in the interim.”

“Is that likely?”

“It’s possible.”

“Can I get some addresses for these people?”

“I thought you’d never ask,” O’Neill said.

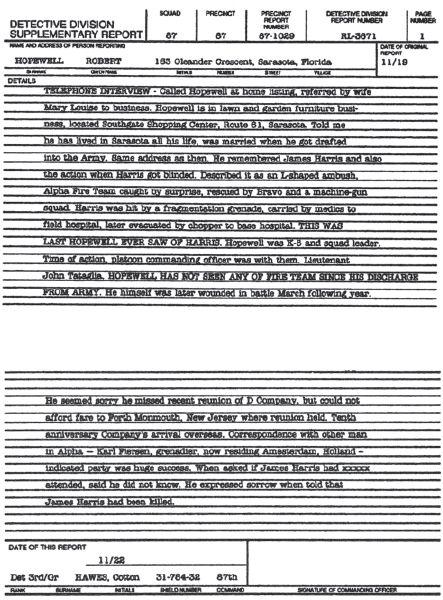

The list of last-known addresses for the four men in Jimmy’s fire team, as well as the man who’d once been his platoon sergeant, broke down this way:

John Francis Tataglia

Fort Lee

Petersburg, Virginia

Rudy Tanner

1147 Marathon Drive

Los Angeles, California

Karl Fiersen

324 Barter Street

Los Angeles, California

Robert Hopewell

163 Oleander Crescent

Sarasota, Florida

Russell Poole, the last man on the list, was also the only man from Alpha who lived in the city. Or, at least, he

had

lived in the city when he was discharged from the army. His address was listed as 3167 Avenue L, in Majesta.

A series of phone calls to Directory Assistance came up with address confirmations for Robert Hopewell in Sarasota and Russell Poole here in the city. There were no telephone listings for Rudy Tanner or Karl Fiersen in Los Angeles; Carella could only assume both men had since moved. There was nothing else he could do to locate them, unless they’d been in trouble with the Law since their discharge. He called the Los Angeles Police Department and asked for a records search in their Identification Section. The detective-sergeant to whom he spoke—in Los Angeles, they were rather more paramilitary concerning rank than were the police in this city—promised Carella he’d get back to him by the end of the day.

Carella then called Fort Lee, Virginia, and learned that John Francis Tataglia, the erstwhile platoon sergeant who’d presumably been promoted to second lieutenant, was now

Major

Tataglia and had been transferred to Fort Kirby this past September. Fort Kirby was in the adjoining state, some eighty miles over the Hamilton Bridge. Carella called the major there at once, and told him he’d be out to see him that afternoon. The major did not remember Pfc. James Harris until Carella explained that he was the man who’d been blinded in action. Cotton Hawes was just coming through the slatted-rail divider as Carella hung up the phone. He signaled to him, and Hawes walked over to his desk; his red hair had been tangled by the wind outside, his face was raw, he looked fierce and mean.

“Are you busy?” Carella asked.

“Why?”

“I need someone to call Sarasota for me, do a telephone interview. I’ve got to go out to Fort Kirby right away.”

“Sarasota? Where’s that, upstate?”

“No, Florida.”

“Florida, huh? Why don’t I just fly on down there?” Hawes said, and grinned.

“Because I also want you to go see a man in Majesta. What do you say?”

“What am I supposed to do with the three burglaries I’m working?”

“This is a homicide, Cotton.”

“

I’ve

got a homicide too,” Hawes said. “Somewhere on my desk, I’m sure I’ve got a homicide.”

“Can you help me?”

“Fill me in,” Hawes said, and sighed.

In order to get to Fort Kirby in the bordering state, one drove over the Hamilton Bridge and through a community called Baylorville, which in the good old days used to be the pig-farming center of the state. Nowadays there was nary an oink to be heard in the vicinity, but the place stank nonetheless, and Meyer put his handkerchief to his nose the moment they began driving through it. He was beginning to discover that he had a very sensitive olfactory mechanism, a quality he had not recognized in himself earlier. He wondered how he could put this to good use in the crime-detection business. Meanwhile, he looked out dismally at the rows of factories and refineries, incinerators and mills that lined the parkway. The weather had turned bleak and forbidding. Even without the benefit of the smokestacks belching their filth and stench into the air, the sky would have been the color of gunmetal.

Both men sat huddled inside their overcoats. It was 12:30 by the car clock, and Fort Kirby was still forty miles away. The parkway tollbooths were spaced exactly five miles apart; Carella kept rolling down the window on the driver’s side and handing quarters to toll collectors. Meyer kept track of the quarters they spent. They would later turn in a chit to Clerical, hoping they’d one day be reimbursed. In the police department, chits were questioned closely, the operative theory being that people in law enforcement were all too often crooks themselves, educated as they were in the ways of thieves. After all, who was to say that the 50¢ spent for a bridge toll had not instead been spent for a hamburger, medium rare? Carella asked for receipts at all of the tollbooths. He handed these to Meyer, who clipped them to the inside cover of his notebook.

It was twenty minutes past 1:00 when they reached Fort Kirby. Carella identified himself to the sentry at the gate in the cyclone fence surrounding the base. A huge sign, black lettered on white, advised that no one but authorized personnel would be admitted to the area. The sentry examined Carella’s shield and ID card, checked a sheaf of slips attached to a clipboard, and then said, “The major’s expecting you, sir. You can park just this side of the canteen, that’s the redbrick building there on your right. The major’s in A-4.”

“Thank you,” Carella said.

Major John Francis Tataglia was a man in his early thirties, with close-cropped blond hair and a blond mustache that hung under his nose like an afterthought. He was slight of build, perhaps five feet nine inches tall, with alert blue eyes and an air of total efficiency about him. You could visualize this man on a parade ground standing at attention in the hot sun, never wilting, never even perspiring. He rose from behind his desk the moment the sergeant ushered Carella and Meyer into his office. He extended his hand.

“Major Tataglia,” he said. “Pleased to meet you.”

Both detectives shook hands with him, and then took seats opposite his desk. The sergeant backed out of the room like an indentured servant. The door whispered shut behind him. From somewhere out on the drill field, they could hear a sergeant bellowing marching orders, “Hut, tuh, trih, fuh,” the repetitive chant oddly and overwhelmingly evocative. For Carella, it recalled his own basic training so many years before. For Meyer, inexplicably, it brought back with an almost painful rush the days when he played football for his high school team. Beyond the major’s wide window, November sprawled leadenly. It was a good month for memories, November.

“As I told you on the phone,” Carella said, “we’re investigating a series of homicides—”

“More than one?” Tataglia said. “When you told me you were looking for information about Harris, I assumed—”

“There’ve been three murders so far,” Carella said. “We’re not sure they’re all related. The first two most certainly are.”

“I see. Who were the other victims?”

“Harris’s wife, Isabel, and a woman named Hester Mathieson.”

“How can I help you?” Tataglia asked.

The top of his desk was clear of papers and even pencils. A brass plaque read

Maj. J. F. Tataglia.

A folding triptych picture frame showed photographs of a dark-haired woman and two little girls, one with dark hair, the other with hair as blonde as the major’s. He touched the tips of his fingers together and held them just under his chin, as though in prayer.

Meyer kept watching him. With his extrasensory olfactory awareness, he detected the scent of cologne emanating from behind the major’s desk. He had never liked men who wore cologne, even if they were athletes being paid to advertise it on television. He did not like Tataglia altogether. There was something prissy about the man, something too starchily precise. He kept watching him. Tataglia had apparently decided Carella was the spokesman here; Meyer watched Tataglia, and Tataglia watched Carella.

“We have reason to believe Harris may have contacted an old Army buddy regarding a scheme of his,” Carella said.

“What sort of scheme?”

“An illegal one, possibly.”

“You say possibly…”

“Because we don’t really know,” Carella said. “You were in command of the 3rd Platoon, is that correct?”

“Yes.”

“Were you present when Harris was blinded?”

“Yes. I later filed the action report.”

“And signed it as commanding officer.”

“Yes.”

“That was on December fifteenth. He was blinded on December fourteenth—is that correct?—and you filed the report on December fifteenth.”

“Yes, those are the dates,” Tataglia said.

“Had you been recently promoted?”

“Yes.”

“Before the action in which Harris…”

“Yes, a week or ten days earlier. We’d begun Operation Ala Moana at the beginning of December. Lieutenant Blake was killed shortly after the choppers dropped us in. I was promoted in the field. For the rest of the operation, I was acting OIC.”

“You were promoted to lieutenant?”

“Yes, second lieutenant in charge of the entire platoon. This was no simple vill sweep, you understand. This was a vast encircling maneuver involving a full battalion—mechanized units, artillery, air support, the works. The day before Harris got blinded, our recon patrol found an enemy base camp a mile to the southwest. We were marching toward it through the jungle when we got hit.”

“What happened?”

“An L-shaped ambush. The first fire team was fully contained in the short side of the L. Bravo was just entering the long side. There was nothing we could do. They’d closed the trail and lined it with rifles and machine guns, and we were caught in the cross-fire. We hit the bushes, hoping they hadn’t been lined with punji stakes, and we just lay there returning fire and hoping Bravo would get to us before we all were killed. Bravo came in with the 3rd Squad right behind them, a machine-gun squad. It was a pretty hairy ten minutes, though. I was amazed we got through it with only Harris getting hurt. A grenade got him, almost tore his head off.”

“No other casualties?”

“Not in Alpha. Two men in Bravo were killed, and the 3rd Squad suffered some wounded. But that was it. We were really lucky. They had us cold.”

“Would you remember which of the men Harris was closest to?”

“What do you mean? In the action? When he was hit?”

“No, no. Who were his friends? Was there anyone he was particularly close to?”

“I really couldn’t say. I’m not sure if you understand how this works. There are forty-four men in a platoon, plus the commanding officer and the platoon sergeant. The lieutenant will usually set up his command post where he can best direct the action. I was with that particular fire team on that particular day because they were first in the line of march.”

“Then you didn’t know the men in Alpha too well.”

“Not as individuals.”

“Even though the operation had started at the beginning of the month?”

“I knew them by name, I knew their faces. All I’m saying is that I had very little personal contact with them. I was an officer, they were—”

“Yes, but you’d only recently been promoted.”

“That’s true,” Tataglia said, and smiled. “But there’s not much love lost between top sergeants and the men under them. I was an E-Seven before Lieutenant Blake got killed.”

“How did he get killed?” Meyer asked.

“Mortar fire,” Tataglia said.

“And this was?”

“Beginning of the month sometime. Two or three days after the drop, I’m not certain of the date.”

“Would you know if Harris kept in touch with any of the men after his discharge?”

“I have no idea.”

“Have

you

been in contact with any of them?”

“The men in Alpha, do you mean?”

“Yes.”

“No. I correspond regularly with the man who commanded D Company’s First Platoon, but that’s about it. He’s a career soldier like myself, stationed in Germany just now, got sent over shortly after the reunion.”

“What reunion is that, Major?”

“D Company had a big reunion in August. Tenth anniversary of the company’s arrival overseas.”

“Where’d the reunion take place?”

“Fort Monmouth. In New Jersey.”

“Did you attend the reunion?”

“No, I did not.”

“Did your friend?”

“Yes, he did. He mentioned it in one of his letters to me. Actually, I’m sorry I missed it.”

“Well,” Carella said, and looked at Meyer. “Anything else you can think of?” he asked.

“Nothing,” Meyer said.

“Thank you very much,” Carella said, rising and extending his hand.

“I’m sorry I couldn’t be more helpful,” Tataglia said.

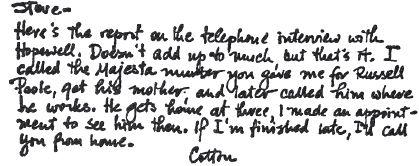

The DD report was on Carella’s desk when they got back to the squadroom. Meyer asked him if he wanted a cup of coffee, and then went down the corridor to Clerical. The clock on the wall read 3:37. The shadows were lengthening; Carella switched on his desk lamp and picked up the report. A handwritten note was fastened to it with a paper clip:

Carella took the paper clip from the report, crumpled Hawes’s note, and threw it in the wastebasket. Hawes was a better typist than most of the men on the squad. The report looked relatively neat:

Majesta, of course, had been named when the British owned America. It had been named after His Majesty King George. Lots of things were named after King George in those days. Georgetown was named after King George. In those days, when the British were dancing quadrilles and even common soldiers sounded like noblemen, Majesta was hilly and elegant. “Oh, yes, Majesta,” the British would say. “Quite elegant.” Majesta nowadays was still hilly, but it was not elegant. It was, in fact, inelegant. In fact, it was what you might call crappy.

There were some people in Majesta who lived all the way out on the tongue of land that jutted into the Atlantic, within the city limits but far from the city proper and also the madding crowd. These people felt that Washington and the Continental Congress had been misguided zealots. These people were of the opinion that Majesta would have fared better as a British colony. A case in point was neighboring Sand’s Spit, which even today seemed very

much

like a British colony. That was because the people out there drank Pimms Cups during the summer months and talked through their noses a lot. The people on Sand’s Spit were enormously rich, most of them. Some of them were only terribly rich. The people in Majesta were miserably poor, most of them. Some of them were only dreadfully poor. Russell Poole was pretty goddamn poor.

He lived with his mother in a row of houses that resembled those one might have found in England along Victoria Street or Gladstone Road—the apple does not fall far from the tree. Russell Poole was black. He had never been to England, but often dreamt of going there. He did not know that England had its own problems with people of a darker hue—the tree does not grow far from the fallen apple. Poole only knew that he was poor and living in a dump. He did not like the looks of Cotton Hawes. Cotton Hawes looked like a mean mother-fucking cop. Poole told his mother to go in the other room.

Hawes didn’t much like the looks of Russell Poole, either.

Actually, the men looked a lot alike, except that one was white and the other was black. Maybe that made all the difference. Poole was about Hawes’s height and weight, a good six feet two inches tall and 190 pounds. Both men were broad-shouldered and narrow-waisted. Poole did not have red hair like Hawes—but then again, who did? Poole closed the door on the bedroom his mother had just entered, and then said, “Okay, what’s this about?”