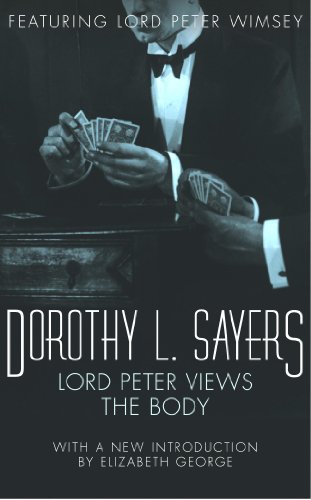

Lord Peter Views the Body

Lord Peter Views the Body

Dorothy L. Sayers

First published in Great Britain in 1928 by Victor Gollancz Ltd

First published in paperback by New English Library in 1974

An imprint of Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette Livre UK company

Introduction © Susan Elizabeth George 2003

The right of Dorothy L. Sayers to be identified as the Author

of the Work has been asserted in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any

means without the prior written permission of the publisher,

nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other

than that in which it is published and without a similar

condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious

and any resemblance to real persons,

living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this title

is available from the British Library

Epub ISBN 9781848943766

Book ISBN 9780450017094

Hodder and Stoughton

An Hachette Livre UK company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

THE STORIES

The Abominable History of the Man with Copper Fingers

The Entertaining Episode of the Article in Question

The Fascinating Problem of Uncle Meleager’s Will

The Fantastic Horror of the Cat in the Bag

The Unprincipled Affair of the Practical Joker

The Undignified Melodrama of the Bone of Contention

The Vindictive Story of the Footsteps that Ran

The Bibulous Business of a Matter of Taste

The Learned Adventure of the Dragon’s Head

The Piscatorial Farce of the Stolen Stomach

The Unsolved Puzzle of the Man with No Face

The Adventurous Exploit of the Cave of Ali Baba

INTRODUCTION

I came to the wonderful detective novels of Dorothy L. Sayers in a way that would probably make that distinguished novelist spin in her grave. Years ago, actor Ian Carmichael starred in the film productions of a good chunk of them, which I eventually saw on my public television station in Huntington Beach, California. I recall the host of the show reciting the impressive, salient details of Sayers’ life and career – early female graduate of Oxford, translator of Dante, among other things – and I was much impressed. But I was even more impressed with her delightful sleuth Lord Peter Wimsey, and I soon sought out her novels.

Because I had never been – and still am not today – a great reader of detective fiction, I had not heard of this marvellous character. I quickly became swept up in everything about him: from his foppish use of language to his family relations. In very short order, I found myself thoroughly attached to Wimsey, to his calm and omnipresent manservant Bunter, to the Dowager Duchess of Denver (was ever there a more deliciously alliterative title?), to the stuffy Duke and the unbearable Duchess of Denver, to Viscount St. George, to Charles Parker, to Lady Mary. . . . In Dorothy L. Sayers’ novels, I found the sort of main character I loved when I turned to fiction: someone with a ‘real’ life, someone who wasn’t just a hero who conveniently had no relations to mess up the workings of the novelist’s plot.

Dorothy L. Sayers, as I discovered, had much to teach me both as a reader and as a future novelist. While many detective novelists from the Golden Age of mystery kept their plots pared down to the requisite crime, suspects, clues, and red herrings, Sayers did not limit herself to so limited a canvas in her work. She saw the crime and its ensuing investigation as merely the framework for a much larger story, the skeleton – if you will – upon which she could hang the muscles, organs, blood vessels and physical features of a much larger tale. She wrote what I like to call the tapestry novel, a book in which the setting is realised (from Oxford, to the dramatic coast of Devon, to the flat bleakness of the Fens), in which throughout both the plot and the subplots the characters serve functions surpassing that of mere actors on the stage of the criminal investigation, in which themes are explored, in which life and literary symbols are used, in which allusions to other literature abound. Sayers, in short, did what I call ‘taking no prisoners’ in her approach to the detective novel. She did not write down to her readers; rather, she assumed that her readers would rise to her expectations of them.

I found in her novels a richness that I had not previously seen in detective fiction. I became absorbed in the careful application of detail that characterized her plots: whether she was educating me about bell ringing in

The Nine Tailors

, about the unusual uses of arsenic in

Strong Poison

, about the beauties of architectural Oxford in

Gaudy Night

. She wrote about everything from cryptology to vinology, making unforgettable that madcap period between wars that marked the death of an overt class system and heralded the beginning of an insidious one.

What continues to be remarkable about Sayers’ work, however, is her willingness to explore the human condition. The passions felt by characters created eighty years ago are as real today as they were then. The motives behind people’s behavior are no more complex now than they were in 1923 when Lord Peter Wimsey took his first public bow. Times have changed, rendering Sayers’ England in so many ways unrecognizable to today’s reader. But one of the true pleasures inherent to picking up a Sayers novel now is to see how the times in which we live alter our perceptions of the world around us, while doing nothing at all to alter the core of our humanity.

When I first began my own career as a crime novelist, I told people that I would rest content if my name was ever mentioned positively in the same sentence as that of Dorothy L. Sayers. I’m pleased to say that that occurred with the publication of my first novel. If I ever come close to offering the reader the details and delights that Sayers offered in her Wimsey novels, I shall consider myself a success indeed.

The reissuing of a Sayers novel is an event, to be sure. As successive generations of readers welcome her into their lives, they embark upon an unforgettable journey with an even more unforgettable companion. In time of dire and immediate trouble, one might well call upon a Sherlock Holmes for a quick solution to one’s trials. But for the balm that reassures one about surviving the vicissitudes of life, one could do no better than to anchor onto a Lord Peter Wimsey.

Elizabeth George

Huntington Beach, California

May 27, 2003

THE ABOMINABLE HISTORY OF THE MAN WITH COPPER FINGERS

The Egotists’ Club is one of the most genial places in London. It is a place to which you may go when you want to tell that odd dream you had last night, or to announce what a good dentist you have discovered. You can write letters there if you like, and have the temperament of a Jane Austen, for there is no silence room, and it would be a breach of club manners to appear busy or absorbed when another member addresses you. You must not mention golf or fish, however, and, if the Hon. Freddy Arbuthnot’s motion is carried at the next committee meeting (and opinion so far appears very favourable), you will not be allowed to mention wireless either. As Lord Peter Wimsey said when the matter was mooted the other day in the smoking-room, those are things you can talk about anywhere. Otherwise the club is not specially exclusive. Nobody is ineligible

per se

, except strong, silent men. Nominees are, however, required to pass certain tests, whose nature is sufficiently indicated by the fact that a certain distinguished explorer came to grief through accepting, and smoking, a powerful Trichinopoly cigar as an accompaniment to a ’63 port. On the other hand, dear old Sir Roger Bunt (the coster millionaire who won the £20,000 ballot offered by the

Sunday Shriek

, and used it to found his immense catering business in the Midlands) was highly commended and unanimously elected after declaring frankly that beer and a pipe were all he really cared for in that way. As Lord Peter said again: ‘Nobody minds coarseness, but one must draw the line at cruelty.’

On this particular evening, Masterman (the cubist poet) had brought a guest with him, a man named Varden. Varden had started life as a professional athlete, but a strained heart had obliged him to cut short a brilliant career, and turn his handsome face and remarkably beautiful body to account in the service of the cinema screen. He had come to London from Los Angeles to stimulate publicity for his great new film,

Marathon

, and turned out to be quite a pleasant, unspoiled person – greatly to the relief of the club, since Masterman’s guests were apt to be something of a toss-up.

There were only eight men, including Varden, in the brown room that evening. This, with its panelled walls, shaded lamps, and heavy blue curtains was perhaps the cosiest and pleasantest of the small smoking-rooms, of which the club possessed half a dozen or so. The conversation had begun quite casually by Armstrong’s relating a curious little incident which he had witnessed that afternoon at the Temple Station, and Bayes had gone on to say that that was nothing to the really very odd thing which had happened to him, personally, in a thick fog one night in the Euston Road.

Masterman said that the more secluded London squares teemed with subjects for a writer, and instanced his own singular encounter with a weeping woman and a dead monkey, and then Judson took up the tale and narrated how, in a lonely suburb, late at night, he had come upon the dead body of a woman stretched on the pavement with a knife in her side and a policeman standing motionless near by. He had asked if he could do anything, but the policeman had only said, ‘I wouldn’t interfere if I was you, sir; she deserved what she got.’ Judson said he had not been able to get the incident out of his mind, and then Pettifer told them of a queer case in his own medical practice, when a totally unknown man had led him to a house in Bloomsbury where there was a woman suffering from strychnine poisoning. This man had helped him in the most intelligent manner all night, and, when the patient was out of danger, had walked straight out of the house and never reappeared; the odd thing being that, when he (Pettifer) questioned the woman, she answered in great surprise that she had never seen the man in her life and had taken him to be Pettifer’s assistant.

‘That reminds me,’ said Varden, ‘of something still stranger that happened to me once in New York – I’ve never been able to make out whether it was a madman or a practical joke, or whether I really had a very narrow shave.’

This sounded promising, and the guest was urged to go on with his story.