Lords of the Sky: Fighter Pilots and Air Combat, From the Red Baron to the F-16 (34 page)

Read Lords of the Sky: Fighter Pilots and Air Combat, From the Red Baron to the F-16 Online

Authors: Dan Hampton

Tags: #History, #United States, #General, #Military, #Aviation, #21st Century

As bad as the Blitz was, it signaled that by Friday, September 13, Goering had given up the war of fighter pilots. With a scant 130 flyers available to the British, it came just in time. Airfields and radars were repaired, spare aircraft were delivered, and pilots got a few precious days of rest, which they hadn’t had since July. This would be a crucial factor over the next week, especially since the Germans had no such break. Astonishingly, the High Command didn’t feel it was needed; indeed, Hitler said on September 14, “There is a great chance of totally defeating the British.”

He’d initially set September 15 as the date for the invasion, and though the invasion didn’t occur, the Luftwaffe sent more than 1,300 sorties against London that day. Fighter Command responded from both 11 and 12 Group with nearly two hundred Spitfires and Hurricanes accounting for fifty-eight Germans shot down, including twenty-six fighters. After what would be celebrated as Battle of Britain Day, it was clear even to Goering and Hitler that the Royal Air Force was not defeated. Adolf Galland got his fortieth kill that month but told Goering to his face, “In spite of heavy losses we are inflicting on the enemy fighters, no decisive decrease in their number or fighting efficiency was noticeable.”

Generaloberst Alfred Jodl, chief of the Wehrmacht Operations Staff, would personally state to Hitler that “under no circumstances must the landing operation fail. The political consequences of a fiasco might be much more far reaching than the military . . . the landing must be considered a desperate venture, something which might have to be undertaken in a desperate situation but on which we have no necessity to embark at the moment.” Jodl also indicated that “England can be brought to her knees by other methods,” such as closing the Mediterranean to the British by taking Gibraltar or cutting England off from the Middle East by seizing the Suez Canal.

Faced with growing losses, bad weather over the Channel, and a worsening situation in North Africa, Hitler postponed Operation Sealion on September 17, 1940. British intelligence intercepted signals ordering that German air transport facilities be dismantled. The raids would continue for several months, with an increasing emphasis on night bombing, which neither primary British fighter was well equipped to meet. The Spitfire was particularly difficult due to its fiery exhaust plumes. Airfield lighting was haphazard, as was aircraft instrumentation for “blind,” or instrument, flying. The Bristol Beaufighter was finally deemed a better choice, since it would have room for an airborne radar and an operator to employ it while the pilot flew. There was also no real interference with night vision, as the engines were on the wings, not in front of the pilot’s face.

Fitted with a Mk IV Airborne Intercept radar by late September 1940, the Beaufighter was armed with four cannons and two machine guns. With a top speed of 320 mph, it wasn’t a survivable fighter during the day, but at night, in the right hands, it was deadly. The most successful hands belonged to Flight Lt. John Cunningham of 604 Squadron. Cunningham learned the radar and night interception tactics to the point where he shot down twenty Germans—nineteen of them at night. He explained his nickname, “Cat’s Eyes,” like this:

I was given the nickname “Cat’s Eyes” by the Air Ministry to cover up the fact that we were flying aircraft with radar because there was never any mention of radar at that period. So by the time I had had two or three successes, the Air Ministry felt they would have to explain that I had very good vision by night . . . it would have been easier had the carrots worked. In fact, it was a long, hard grind and very frustrating. It was a struggle to continue flying on instruments at night.

On September 30 the final major daylight on London was launched. German losses that day totaled some forty-three aircraft destroyed against sixteen for the RAF, and the threat of invasion followed the myth of Luftwaffe superiority into history. The battle would continue for another two months, finally ending on December 18, as Hitler began preparations for the invasion of the Soviet Union.

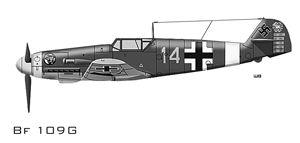

Statistics relative to the battle are as varied as the number of agencies involved. The Luftwaffe started the fight in June with about 4,000 aircraft, of which 1,107 were Bf 109s and 357 were Bf 110s, for a total of 1,464 fighters. There were 1,450 fighter pilots to fly them, including highly experienced veterans of Spain, Poland, Norway, and France. Over the course of the battle, the Royal Air Force would claim 2,698 German planes (of all types) destroyed. The reality, according to postwar sources, was closer to 1,600, of which 762 were fighters. This tallies more closely with the known Luftwaffe record of more than 2,500 aircrew killed and 967 captured.

The Royal Air Force began the battle with 800 fighter aircraft, mostly Hurricane Mk Is and a few Spitfires. More than 400 fighter pilots had been lost during the Battle of France, so the RAF had about 1,000 remaining. This would be augmented by another 400 foreign pilots who’d escaped from the Germans and 600 more from the Dominions. The Luftwaffe would claim 3,198 kills during the battle, though the true losses were much less. Actually, 1,087 fighters were lost, plus bombers and Coastal Command aircraft, for a total of 1,600 aircraft. Of the fighter pilots, 900 would be killed, missing, or wounded—a 40 percent casualty rate.

The Battle of Britain is one of those pivots upon which history was decided. It marked Hitler’s farthest western expansion and shattered the very real psychological advantage that the Germans had enjoyed. They

could

be beaten, and had been. On a more practical level, the battle bled the Luftwaffe of vital equipment and irreplaceable men at a time when it could ill afford the loss. This would make a crucial difference in the months to come as 1940 ended and Hitler’s eyes turned south and east.

The British got a new lease on life. Not only had they stopped the most powerful air force in the world, but they had gained time to rebuild and replenish, time to get off the defensive and go offensive. Most important, the outcome signaled to the United States that victory was possible. But the two men who did so much to win the Battle of Britain were shamefully treated. Hugh Dowding was more or less forced to retire once the danger was over and “new ideas” were needed. He went quietly. Leigh-Mallory and his cronies also managed to remove Keith Park, who, unsurprisingly, did not go quietly. His disgust and contempt for political maneuvering at this dangerous juncture was very evident. As Lord Tedder, the chief of the Air Staff, would say of Park:

If any one man won the Battle of Britain, he did. I do not believe it is realized how much that one man, with his leadership, his calm judgment and his skill, did to save, not only this country, but the world.

No one has ever said as much about Park’s critics.

*

It has been quite correctly pointed out that the fight was won by

everyone

who took part, from the civilians who put out fires and repaired aircraft to the women who built more planes and ran Dowding’s Chain Home system. There were bomber pilots who bravely attacked the Third Reich on lonely night missions and never returned. And credit must go to all on the island who refused to surrender when the world said it was impossible to stop Hitler.

However, it was the fighter pilots, alone in their cockpits, who lashed out against waves of enemy bombers and their escorts. These were men who fought within sight of those on the ground—even their own families. These were men who perished, screaming in burning cockpits or died lonely, freezing deaths bobbing helplessly in the Channel. As Winston Churchill expressed in his immortal speech:

The gratitude of every home in our Island, in our Empire, and indeed throughout the world, except in the abodes of the guilty, goes out to the British airmen who, undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning the tide of the World War by their prowess and by their devotion. Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few. All hearts go out to the fighter pilots.

The Battle of Britain was over.

Now the battle for the rest of the world was about to begin.

“

PAUKE . . . PAUKE

. . . Indianer . . . Zehn heur!”

*

Three other helmeted and goggled heads swiveled to the ten o’clock low position and squinted through the glare. How their flight leader could see “Indians”—slang for the enemy—or anything against the bright sand was beyond them, but he always did. The lead Messerschmitt didn’t wait for a reply but simply rolled inverted and pulled down toward the hard, tan Libyan earth.

“Horrido!”

*

British Hurricanes were diving down toward the Stukas and their close escorts, but they hadn’t seen the high group of Bf 109s dropping down on

them

. For Lieutenant. Hans-Joachim Marseille, it was a perfect situation. He jockeyed the throttle and stick to come screaming in behind the other fighter. Much, much faster than his target, Marseille had only a second or two to aim, fire, and reposition away. The Bf 109 Emil shuddered as he triggered off a short burst, paused a split second, then pulled hard away.

His twenty machine gun and cannon rounds went straight into the Hurricane’s left wing, through the cockpit and into the engine. The fighter came apart smoking, and as Marseille rolled and the horizon spun, something hit the Emil—hard. Reacting instantly, Marseille pulled around to the northwest toward the German lines. Leveling off, he trimmed the 109 and quickly scanned his engine instruments. There—just to the right of the stick, the coolant temperature gauge was spiked in the red. Overheat. Whatever came off the Hurricane had hit his radiator, and the glycol was leaking out fast. With his right hand he opened the radiator flaps all the way.

Radioing his

schwarm

that his engine was hit, the twenty-three-year-old

experte

glanced at his altitude, his airspeed, and the endless wasteland stretching out beneath him. Plenty of altitude . . . he could make it back to Derna as long as his motor didn’t quit.

Suddenly the engine knocked violently as the last of the coolant drained away. Reaching up with his left hand, Marseille cut off the fuel, then stared out to his left and realized he couldn’t make Derna. But Matruba was 10 miles closer, and that would be no problem.

As he calmly radioed in his coordinates, something glinted below him. Sunlight on metal! He had excellent eyes, and as they narrowed against the glare he picked up another Hurricane. It was a good 5,000 feet lower and turning to attack, which was what had caused the wing flash. Never hesitating, Marseille instantly split-S’d down, converting the complex geometrical problem into stick and rudder movements. The planes rolled out nose to nose, with the German coming down. As the Hurricane’s nose lifted Marseille opened fire, sending the other fighter diving into the ground.

Immediately zooming back up and turning toward Matruba, he bunted over to hold best glide speed. A few minutes later he coasted over the threshold, gear down, and made a superb dead-stick landing. Rolling out, he unlatched the canopy, and the morning air dried his sweat. It was just past 0930 on February 13, 1942. Two Hurricanes shot down, thanks to another magnificent feat of flying, and his damaged Emil would fly again in three days. Locking the parking brake, the young pilot smiled, looking very boyish at the thought of his forty-fifth and forty-sixth kills. Pulling himself up and sitting on the canopy rail, he listened to the engine tick and watched the ground crews race toward him, the battered

Kübelwagens

stirring up the ever-present dust. This had been a good morning.

But it hadn’t always been like this.

Hans-Joachim Marseille had been flying since he was eighteen. Born into a military family, son of a rigid German officer father, he was a rebel from his first step. Entering the Luftwaffe, he waltzed through flight school and was sent to fighters. A gifted natural pilot with a photographic memory, he was sent to the famous Jagdfliegerschule 5 in November 1939. As Marseille mastered aerobatics, navigation, and gunnery, his natural rebelliousness began to attract attention.

It must be appreciated that Nazi Germany in 1939 was

not

the place to be a nonconformist. There was no freedom of speech, much music (including American jazz) was banned, and undesirable people often just disappeared. Marseille simply didn’t care. He drank, which was a serious offense, and fast became one of the most infamous womanizers in the Luftwaffe. He was in trouble so often that, according to one of his friends, “it was a noteworthy occasion when he was not on restriction.”

He was late. He missed additional duties. One time on a cross-country training flight he landed on the Autobahn to relieve himself. Despite Germany’s need for pilots and his obvious skill, everyone believed Marseille would wash out to the infantry. But he didn’t. Whether it was luck or his father’s good connections, he managed to graduate and was posted to Lehrgeschwader (LG) 2 in August 1940. Flying out of Calais-Marck at the height of the Battle of Britain, he was in combat within days. On August 24 he spotted a Hurricane over Kent in southern England and, without saying a word, deserted his flight and attacked.

*

The British fighter fell into the water, and Marseille was ecstatic—until he landed, to face his commander.