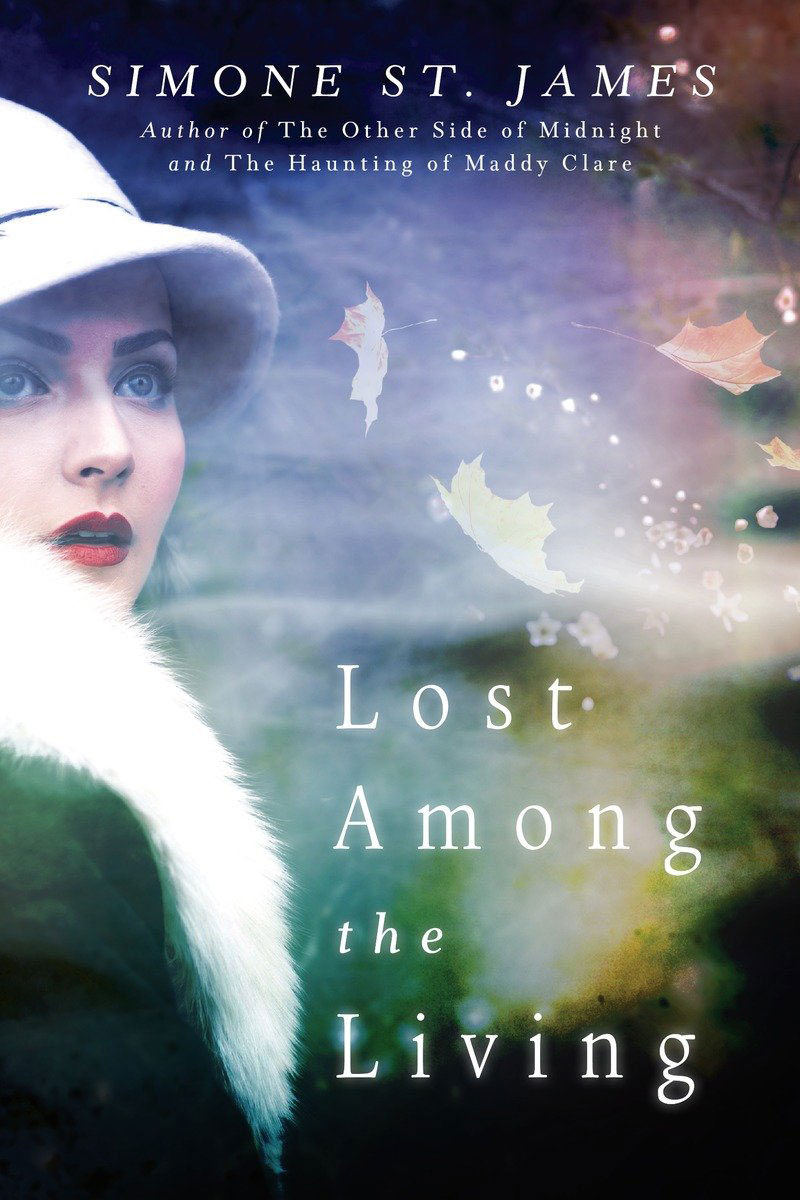

Lost Among the Living

Read Lost Among the Living Online

Authors: Simone St. James

PRAISE FOR THE NOVELS OF SIMONE ST. JAMES

The Other Side of Midnight

“No one mixes romance, mystery, and that faint, spine-tingling sense of the supernatural, that curtain lifting in a breeze that isn't there, the hair prickling on the back of your neck, like Simone St. James. Her novels are the perfect combination of classic ghost story, historical fiction, and romantic suspense.”

âLauren Willig, author of the Pink Carnation series and

The Other Daughter

“St. James stages a thoroughly gripping murder mystery. . . . St. James's intense story drips with atmosphere and emotion. Set in the time between world wars when spiritualist belief ran high, this briskly paced mystery offers action, romance, and a puzzle that proves talking to the dead isn't a gameâand can be deadly.”

â

Publishers Weekly

“Simone St. James has once again crafted a headily atmospheric and suspenseful mystery that kept me reading until the wee hours.”

âJennifer Robson, author of

Somewhere in France

and

After the War Is Over

“Lyrical writing, chilling ghost stories, complicated characters, and gripping mysteries are all contained in the wonderful books of Simone St. James.”

â

RT Book Reviews

(top pick, 4½ stars)

“Simone St. James has created her own genreâhistorical gothic mystery romance, with more than a dash of the creepy.”

âSusan Elia MacNeal,

New York Times

bestselling author of the Maggie Hope Mysteries

Silence for the Dead

“Kudos for Simone St. James. I was swept away by this atmospheric and truly spine-chilling page-turner. . . . If you love a good ghost story, you will be entranced.”

âMary Sharratt, author of

The Real Minerva

and

Daughters of the Witching Hill

“A twenty-first-century version of Mary Stewart. . . . St. James layers the atmosphere with the requisite dread, and one can't help but read on. . . . Just the right mix of suspense, creepiness, and empathy.”

â

National Post

(Canada)

“Vivid, eerie, and atmospheric. St. James's latest will simultaneously tug at your heartstrings and send chills down your spine. Absolutely riveting.”

âAnna Lee Huber, author of the Lady Darby Mysteries

“Aficionados of the classic gothic style in the tradition of Victoria Holt won't want to miss this atmospheric tale of romantic suspense.”

â

Library Journal

An Inquiry into Love and Death

“At once an intriguing mystery and an eerie ghost story, it had more than enough spine-tingling moments to keep me gripped. The perfect book to curl up with by the fire on a stormy night . . . although perhaps not by yourself in an empty house!”

âKatherine Webb, author of

The Unseen

“Another chilling story. . . . St. James delivers a quickly paced read that will satisfy both new and old fans.”

â

Publishers Weekly

“This is a perfectly balanced combination of mystery, romance, ghost story, and history.”

â

RT Book Reviews

(top pick, 4½ stars)

The Haunting of Maddy Clare

“Downright scary and atmospheric. I flew through the pages of this romantic and suspenseful period piece.”

âLisa Gardner, #1

New York Times

bestselling author of

Crash & Burn

“An inventively dark gothic ghost story. Read it with the lights on. Simply spellbinding.”

âSusanna Kearsley,

New York Times

bestselling author of

A Desperate Fortune

“A compelling read. With a strong setting, vivid supporting characters, and sympathetic protagonists. . . . Simone St. James is a talent to watch.”

âAnne Stuart,

New York Times

bestselling author of

Consumed by Fire

“A compelling and beautifully written debut full of mystery, emotion, and romance. . . . Great story, believable characters, wonderful writingâI couldn't put this down.”

âMadeline Hunter,

New York Times

bestselling author of

His Wicked Reputation

Other Books by Simone St. James

The Haunting of Maddy Clare

An Inquiry into Love and Death

Silence for the Dead

The Other Side of Midnight

NEW AMERICAN LIBRARY

Published by New American Library,

an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014

This book is an original publication of New American Library.

Copyright © Simone Seguin, 2016

Readers Guide copyright © Penguin Random House, 2016

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

New American Library and the New American Library colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

For more information about Penguin Random House, visit

penguin.com

.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-698-19847-0

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG

ING-IN-PUBLICATION D

ATA:

Names: St. James, Simone, author.

Title: Lost among the living/Simone St. James.

Description: New York, New York: New American Library, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2015039480 | ISBN 9780451476197 (softcover)

Subjects: LCSH: FamiliesâEnglandâFiction. | Family secretsâFiction. |

BISAC: FICTION/Historical. | FICTION/Ghost. | FICTION/Romance/Gothic. |

GSAFD: Gothic fiction. | Mystery fiction. | Ghost stories.

Classification: LCC PR9199.4.S726 L67 2016 | DDC 813/.6âdc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015039480

PUBLISHER'S NOTE

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Version_1

For Adam

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many thanks to both of my editors on this book. To Ellen Edwards: Five books with you has been nothing short of an honor and a privilege. To Danielle Perez: I hope this will be the start of many great books together. Thanks as always to my agent, Pam Hopkins, for advising me in this crazy business. I give gratitude every day for my wonderful mother, brother, and sisterâI love you all. Molly, Maureen, Tiffany, Sinead, Stephanieâyou cannot know how you save my sanity on a regular basis. My extended family has been supportive from the very first. And, as always, Adam, this is not possible without

you.

ENGLAND, 1921

B

y the time we left Calais, I thought perhaps I hated Dottie Forsyth. To the observer, I had no reason for it, since by employing me as her companion Dottie had saved me from both poverty and a life robbed of color in my rented flat, the life I was trying to live without Alex. However, the observer would not have had to spend the past three months crisscrossing Europe in her company, watching her scavenge for art as cheaply as possible while smoking her cigarettes in their long black holder.

“Manders,” she said to meâthough my name was Jo, one of her charms was the habit of calling me by my last name, as if I were the upstairs maidâ“Mrs. Carter-Hayes wishes to see my photographs. Fetch my photograph book from my luggage, won't you? And do ask the porter if they serve sherry.”

This as if we were on a luxurious transatlantic ocean liner, and not on a simple steamer over the Channel for the next three hours. Still, I rose to find the luggage, the photograph book, and the porter, my

stomach turning in uneasy loops as I traveled the deck. The Channel wasn't entirely calm today, and the misty gray in the distance gave a hint of oncoming rain. The other passengers on the deck gave me only brief glances as I passed them. A girl in a wool skirt and a knitted cardigan is an unremarkable English sight, even if she's passably pretty.

I found the luggage compartment with the help of the porter, whose look of surprise turned to one of pity when I asked about the sherry, and from there I rummaged through Dottie's many bags and boxes, looking for the slender little photograph book with its yellowed pages. I didn't think Mrs. Carter-Hayes, who had been acquainted with Dottie for all of twenty minutes, had any real desire to see the photographs, but perhaps because of the pointlessness of the mission, I found myself lingering over it, taking longer than I needed to in the quiet and privacy of the luggage compartment. I tucked a lock of hair behind my ear and let out a breath, sitting on the floor with my back to one of Dottie's trunks. We were going back to England.

Without Alex, I had nothing there. I had nothing anywhere. I had given up my flat when I'd left with Dottie, taken the last of my belongings with me. There wasn't much. A few clothes, a few packets of beloved books I couldn't live without. I'd sold off all our furniture by then, and I'd even sold most of Alex's clothes, a wrench that still made me sick to my stomach. I wasn't afraid of poverty; before Alex had swept me into the grand adventure of our marriage, poverty had been all I knew, and it was as familiar to me now as the old cardigan I wore. There was no room for sentiment when you were poor.

The only fanciful thing I'd kept was Alex's camera, which I could have gotten a few pounds for but hadn't been able to part with. The camera had come with me on all of my travels, on every boat and train, though I hadn't even opened the case. If Dottie had noticed, she had made no comment.

And so my life in England now sat before me as a perfect blank. We were to go to Dottie's home in Sussex, a place I had never seen. I was to stay on in Dottie's pay, even though she was no longer traveling

and my duties had not been explained. When she had first written me, declaring starkly that she was Alex's aunt, that she'd heard I was in London, and that she was in need of a female companion for her travels to the Continent, I'd imagined playing kindly nursemaid to an undemanding old lady, serving her tea and reading Dickens and Collins aloud as she nodded off. Dottie, with her scraped-back hair, harsh judgments, and grasping pursuit of money, had been something of a shock.

I tried to picture primroses, hedgerows, and soft, chilled rain. No more hotels, smoke-filled dining cars, resentful waiters, or searches through unfamiliar cities for just the right tonic water or stomach remedy. No more sweltering days at the Colosseum or the Eiffel Tower, watching tourists blithely lead their children and snap photographs as if we'd never had a war. No more seeing the names of battlefields on train departure boards and wondering if that oneâor that one, or that oneâheld Alex's body forgotten somewhere beneath its newly grown grass.

I would have to visit Mother once I was back; there was no escaping it. And I did not relish living on another woman's charity, something I had never done. But at least at Dottie's home I would be able to avoid London, and all of the places Alex and I had been. Everything about London since he'd gone to war the last time had stabbed me. I never wished to see it again.

Eventually I gave up the musty silence of the luggage compartment and returned to the deck, photograph book in hand. “What took so long?” Dottie demanded as I approached. She was sitting in a wooden folding chair, her cloche hat pulled down against the wind and her feet in their practical oxfords crossed at the ankles. She looked up at me, frowning, and though the cloudy light softened the edges of her features, I was not fooled.

“They don't serve sherry here,” I said in reply, handing her the book.

Dottie's eyes narrowed perceptibly. I thought she often convinced

herself that I was lying to her, though she could not quite figure out exactly when or why. “Sherry would have been most

convenient,

” she said.

“Yes,” I agreed. “I know.”

She turned to her companion, a fortyish woman with a wide-brimmed hat, sitting on the folding chair next to hers and already looking as if she wished to escape. “This is my companion,” she said, and I knew from her tone that she intended to direct some derision at me. “She's the widow of my dear nephew Alex, poor thing. He died in the war and left her without children.”

Mrs. Carter-Hayes swallowed. “Oh, dear.” She looked at me and flashed a sympathetic smile, an expression that was so genuine and kind that I almost pitied her for the next three hours she'd have to suffer in Dottie's company. When Dottie was in a mood like this, she took no prisonersâand she'd been in this mood more and more often the closer we came to England.

“Can you imagine?” Dottie exclaimed. “It was a terrible loss to our family. He was a wonderful young man, our Alex, as I know well, since I helped raise him. He spent several years of his childhood living with me at Wych Elm House.”

Her glance cut to me, and in its gleam of triumph I knew that my shock showed on my face. Dottie smiled sweetly. “Didn't he tell you, Manders? Goodness, men are so forgetful. But then, you weren't together all that long.” She turned back to the bewildered Mrs. Carter-Hayes. “Children are life's greatest joy, don't you agree?”

It would go on like this, I knew, until we docked: Dottie speaking in innuendoes and double meanings, cloaked in polite small talk. I moved away and stood by the railâthere was no folding chair for meâand let the noise of the wind blow the words away. I hadn't bothered with a hat, and I felt my curls come loose from their knot and touch my face, my hair tangling and my cheeks chapping as I watched the water sightlessly.

This wasn't her only mood; it was just one of them, though it was

the most vicious and unhappy. Over the last three months I had learned to navigate the maze of Dottie's ups and downs, a task I'd learned naturally, as I was well versed in unhappiness myself. She was fiftyish, her body narrow and strangely muscular, her face with its gray-brown frame of meticulously pinned-back hair naturally sleek, with a pointed chin. She looked nothing like Alex, though she was his mother's sister. She was not vain and never resorted to powders or lipsticks, which would have looked absurd on her tanned skin and narrow line of a mouth. She ate little, walked often, and kept her hair tidy and her clothes mysteriously immaculate, even when traveling. All the better for chasing and devouring her prey.

I glanced back at her and found that she was now displaying the photographs to Mrs. Carter-Hayes. She kept six or seven of them in the slender photograph book, on hand for occasions in which she had cornered a stranger and wished to show off. From the softening of Dottie's features I could tell that she was looking at the picture of her son, Martin, in his officer's uniform. I had seen the photograph many times, and I had heard the accompanying narrative just as often.

He is coming home to be married. He is such a dear boy, my son.

The listeners were always too polite, or too bored, to question the fact that the war had ended three years ago, yet Dottie Forsyth's son was only now coming home. That she still showed the photograph of Martin in uniform, as if she hadn't seen him since it was taken.

There had been a daughter, tooâI knew that much from Alex.

My queer cousin Fran,

he had said, in one of the few times he had referred to this side of the family at all. Queer cousin Fran had died in 1917, though Alex's letter from the Front had not said how or why.

She has died, poor thing,

he wrote.

Are the rations as bad back home as I hear?

He never spoke of her again, and in the months I'd worked for her, Dottie had never mentioned her queer daughter Fran at all. Her photograph was certainly not in the book.

I turned back to the water. I should quit. I should have done it long ago. The position was unpleasant and demeaning. I had been a

typist before I married Alex, before my life had been blown upward like a feather, then come down again. My skills were now rusty, but it was 1921, and girls found jobs all the time. I could try Newcastle, Manchester, Leeds. They must need typists there. It wouldn't be much of a life, but I would be fed and clothed, with Mother's fees paid for, and I could stay pleasantly numb.

But I would not quit. I knew it and, I believed, so did Dottie. It wasn't the pay she gave me, which was small and sporadic. It wasn't the travel, which had simply seemed like a nightmare to me, as if I were taking the train across a vast wartime graveyard, the bombed buildings just losing their char, the bodies buried just beneath the surface of the still-shattered fields. I would not quit because Dottie, viperish as she was, was my last link to Alex. And though it hurt me even to think of him, I could not let him go.

I had last seen him in early 1918, home on leave before he went back to France to fly more RAF missions, the final one from which he did not return. His plane was found four days later, crashed behind enemy lines. There was no body. The pack containing his parachute was missing. He had not appeared on any German prisoner-of-war rosters, any burial details, any death lists. He had not been a patient in any known hospital. The Red Cross, in the chaos after Armistice, did not have him on any prisoner or refugee lists. In three years there had been no telegram, no cry for help, no sighting of him. He had vanished. My life had vanished with him.

He died in the war,

Dottie had said, but it was just another sting of hers. According to the official record, my husband had not died in the war. When there is a body, a grave, then a person has died. But no one ever tells you: When you have nothing but thin air, what happens then? Are you a widow, when there is nothing but a gaping hole in what used to be your life? Who are you, exactly? For three years I had been trapped in amberâfirst in my fear and uncertainty, and then in a slow, chilling exhale of eventual, inexorable grief.

As long as I was with Dottie, part of me was Alex's wife. He still existed, even if only in the form of Dottie's innuendoes and recriminations. Just hearing someoneâanyoneâsay his name aloud was a balm I could not let go of. I had followed her across Europe for it, and now I would follow her to Wych Elm House, her family home. Where Alex had lived part of his childhood, something he had never thought to tell me.

I stared out to sea, uneasy, as England loomed on the horizon.