Lost Worlds (12 page)

No, you wouldn’t, my adventurer voice informed me. You’d know you failed.

So I kept on going.

The ankle complained a little, especially when I squeezed its swollen components into my damp boot. But it responded well to a tentative stroll around the hut. I’d been lucky. It could have been a lot worse. I was going to make it to the top after all!

The trail began the same way it had ended the previous evening. More snarled roots and mud slides and boggy patches. I discarded my bamboo walking staff, now badly cracked, and cut a fresh one.

The sun began to appear in patches and the mists lifted even higher as I entered one of the strangest regions of the Ruwenzori. I’d heard about it from a couple of world wanderers I’d met on the riverboat but never expected to find such an other-planet environment.

There were no trees now, just great upward sweeps of moss and high-elevation grasses. But rising out of this relatively benign surface was a Hollywood film set for a days-of-the-dinosaurs fantasy movie. Enormous twenty-foot-high versions of the familiar ankle-high lobelia surged like fiery spears into the clearing sky; equally tall groups of triffidlike groundsels and senecios, crowned with thick cabbagelike rosettes of leaves, rose on ancient thigh-thick trunks encased in the dead and rotting layers of previous “crowns.” The chill breezes made these creatures sway as if alive; their brittle appendages rattled like skeleton bones.

Scattered between these enormous freaks of nature were large golden-tinged mounds of moss that had surged unchecked over long-dead and fallen groundsels. Other, less familiar plants filled in the spaces—bushes with fat spongy leaves and thin candlelike flowers, tall shrubs that felt like latex foam, great swaths of ferns and bracken bathed in mist-moisture, and, in the clefts of distant cliffs, what looked like giant gorse bushes sprinkled with bright lemon flowers.

An alien, magical place.

I sat on a lichen-covered rock and gazed around in open-mouthed awe. The expression “lost world” took on new, fresh meanings here. I gave thanks that my ankle had held up and that I hadn’t been forced to turn back the previous day. To have missed this experience would have been one of the greatest disappointments of all my lost world odysseys.

There are sound scientific reasons for the profusion of such unique species in this very high environment—a lack of competitive forest, which allows plants to grow to previously unrecorded heights, supported by vast amounts of year-round rain, rich mineral soils, and unusually high levels of ultraviolet radiation. But such explanations in no way diminished the impact of just being here, touching these strange growths and experiencing the deep mysteries of this place.

I arrived late in the afternoon at the third hut, Kiondo, and, once again, found the place empty. My energy seemed boundless. The day’s walk up through the “pterodactyl territory” had been relatively easy, with no mishaps. The mist had vanished, the sun was shining, and the high clouds were lifting off the peaks. Maybe at last I’d see what I’d been hoping to see for days—the summits of the Ruwenzori.

A path meandered away from the hut to the ridge of Musswa-Messo, a mere five hundred feet or so higher up. I was already at fourteen thousand feet and it looked like an easy stroll. According to my map I’d be able to get a much better view of the mountains from that vantage point, so I left my backpack in the hut by the stove and set off up the springy moss-flecked ground singing my walking song.

And I had it all.

As I scrambled up the last few feet to the grassy summit, the remaining shards of cloud slid off the peaks and there they were: Mount Stanley, Mount Margherita, and the other peaks; the enormous Stanley glacier, cracked and broken and blinding white; the appropriately named Lac Vert and Lac Noire nestled in their mountain bowls; and, far below, the great swaths of giant lobelia, seneca, and groundsel I’d hiked through earlier in the day. The vista was incredible—ice-etched ridges, the broken frost-shattered pyramids and pylons of granite pinnacles, snowfields as smooth as cake icing—all backdropped by a searing cobalt-blue sky.

In places where the Stanley glacier had cracked to reveal the interior of its two-hundred-foot-thick ice pack, I could make out the precise layerings of the seasonal ice accumulations, some divided by dark bands of soot and windblown charcoal carried to those heights during gigantic bush fires on the western plains of Zaire and the Congo.

It was getting colder as the sun eased down into the hazy plateau thousands of feet below, but I was reluctant to leave my aerie. This was exactly what I’d come to see—the splendor of Africa’s most mysterious mountains. The discomforts of the cold hut were meager enticements. I remained where I was, silent and happy.

And tomorrow I’d try for the summit of Margherita. Up the long rock walls, across the ice fields, to touch the 16,763-foot peak. It looked so close. So accessible. It was all waiting for me. Worth every one of the terrors and tribulations of the long journey from Kinshasa.

But fate works in odd and often unkind ways. Coming down from Musswa-Messo I was so entranced by the evening clarity of the scene and the soaring perfection of the peaks, I forgot that I was still on dangerous ground, slick with mud and littered with loose rocks.

The fall came so suddenly I hardly noticed it. One moment I was gazing at the glacier, the next I was flat on my back in the mud and scree with my ankle—my right ankle again—badly twisted and sending those now-familiar spears of pain up my leg and thigh.

Goddamn it! I’d done it again. Further damaging the already weak joint. And this time I knew it was more than a mere bruising. Something felt very wrong. If it wasn’t broken I’d certainly torn tendons and Lord knows what else. My left elbow had also taken a hell of a knock on a piece of jagged granite and my lower arm and fingers felt numb.

Much later, after hopping down the few hundred feet to Kiondo hut, I lit a fire, removed my boots, wrapped the now-blue and swollen ankle in tight elastic bandages, and cooked another tasteless dehydrated dinner. I then swallowed a cluster of aspirins and tried to sleep.

But fate hadn’t finished with me yet.

During the night a rainstorm began and a furious howling of cold winds blew the pouring water right through the smashed windows. Sleep was impossible and, although my waterproof sleeping bag gallantly kept me dry, my mood descended to pitlike depths. The ankle throbbed and gave me those branding-iron burns every time I tried to move it to a more comfortable position. Swigs of whiskey-Zairois had no impact on the pain or my increasing depression.

The early morning light merged with the miasma of the scene. Except there was no scene, really. It was just fog. Wafting masses of the stuff. Blowing through the windows in wraithlike curlicues and billowing about outside the hut.

The lukewarm coffee tasted like mud. I ate the last of my chocolate and mint cake in the hope of releasing some latent energy. My mood only worsened. I’d been shown all that was before me—so close, so tangible—only to have it whisked away like a dream. To climb farther was obviously impossible; even to descend was highly questionable with an ankle as fragile as a feather.

I hit the bottom of the spiritual barrel and began to wallow in surges of self-pity and self-recrimination.

Then—voices. Faint at first, then louder. Shouts, laughs, cheers. A lot of people, by the sound of it.

And a lot of people it was—four red-cheeked, dripping wet bronzed faces peering at me through the open doorway, and behind them a bunch of black faces with foreheads covered by the burlap straps of loads on their shoulders and backs.

“Ah

—guten morgen!

” A giant of a man beamed at me in my sprawled state by the smoldering fire. Everyone else smiled too. The elusive German climbers had finally turned up and I began to feel better immediately.

And better still, because they replenished the fire, made fresh coffee, and handed me slabs of salami and bread and strong cheese, and told me tales in broken English of the terrors they’d experienced on the higher slopes when they’d attempted to make the climb that morning from the final hut. Blizzards like they’d never known before, even in the Austrian Alps; two of the party almost lost over an ice fall; winds that blew them off their feet even when they weren’t moving.

They had decided to abandon the climb and get down to the lower huts as soon as possible. Their guides had told them it would get much worse and by the look of the fog outside I agreed with them.

One of the climbers inspected my ankle with long physician’s fingers and declared it badly sprained but possibly adequate for the hike down if I avoided any more falls. He bound it up again tightly in fresh bandages and helped me squeeze it into my boot.

Half an hour later we were on our way down, moving through the mists that made the giant lobelias and groundsels look even more ominous and otherworldish. I was dreading the tangles of the heather forests, but the climbers had appointed one of the porters as my personal guardian and physical support on the rougher slopes.

For much of the way the pain and discomfort of the ankle focused my mind on the trail. I was hardly aware of anything except the nature of the ground directly in front of me. Every root and rut was noted and avoided. On the more difficult stretches I leaned on my porter with my arm around his shoulder. He seemed amused by the familiarity. Maybe even pleased that he’d been able to relinquish his heavy pack for the relative ease of supporting this weary, pain-wracked wanderer. I taught him some of the lines to my marching song and we sang it together in terrible disharmony as the downhill trail went on and on and on….

The next day, back in Beni, I treated the four Germans to the closest thing to a slap-up dinner my modest hotel could provide. Not a memorable feast but certainly a memorable celebration of their concern and kindness.

They were as disappointed as I that we’d not made the summit of Margherita, but, after downing more than our sensible share of Primus beers and glasses of whiskey-Zarois, we peered out of the grubby windows in the evening light and laughed ourselves daft at the view.

Zaire had won. For a few brief tantalizing moments Mount Stanley and all the other peaks sparkled brilliant gold and orange in the setting sun, ice fields flashing, ridges outlined in silver…then they slowly vanished again back into their cloud cocoon. A final ironic reminder of our mutual failure. Only our laughter outlasted the brief sighting as we all realized we were content just to have been here and to have shared the visions of this strange and magnificent—if occasionally malevolent—place.

It was all the fault of a novelist who couldn’t make up his mind what to write next.

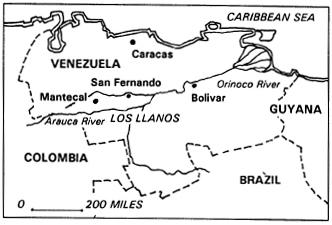

In 1927, around about Easter, Rómulo Gallegos was wandering South America in search of inspiration for his next book. He was a restless, impetuous man constantly starting projects and then abandoning them in favor of new ideas. But he found abundant grist in Venezuela, where citizens are full of tales and the country itself is an incendiary catalyst of inspiration. The scenery is remarkably diverse—from the uncrowded white sand beaches of the Caribbean coast and islands and the great sprawling delta of the Orinoco to the frost-shattered peaks of the high Andes and the mysterious “lost worlds” of the Gran Sabana, where hundreds of vertical-sided mountains (

tepuis

) rise like unearthly totems out of the trackless Amazonian jungle.

Gallegos was boggled by options. His publisher was restless. Two manuscripts lay stranded in midinspiration. He was not a happy man.

Until he met the

llanero—

a cowboy of the plains.

Now,

llaneros

love to talk. Any subject will suffice, but one close to their hearts is their homeland, Los Llanos, a vast six-hundred-mile-long by two-hundred-mile-wide plain in the heart of Venezuela occupying almost a third of the nation. The southern part, drained by the slow-flowing Apure and Arauca rivers, is the wildest part of the Llanos. The land has many of the features—or rather, nonfeatures—of the sprawling grasslands of Brazil’s Pantanal and the Argentina pampas. To call the region flat is like calling a Lamborghini a car. It is one of the flattest places on earth. Beyond a few scraggly hummocks (

matas

) of mapora palms and araguaneys (Venezuela’s national tree), the eye scours the horizons for any sign of variations in the unremitting horizontality. A little less rain and the place would be a desert stretching out to hazy infinities in every direction. But it does rain. Incessantly, between May and November, turning the plain into an enormous shallow lake. Birds flock here by the millions. Some leave at the onset of the dry season, but most remain, making Los Llanos one of the earth’s most important breeding reserves and a hot spot on ornithologists’ maps. Well over 250 species make their homes here, not to mention the alligators, capybaras (almost hunted to extinction when the Catholic church announced that, as the creature could swim, it could be eaten on “fish Fridays”), foxes, peccaries, agoutis, anteaters, tapirs, howler monkeys, ocelots, coati, wild boars, anacondas, and even the elusive jaguar.

The famous explorer/navigator Alexander von Humboldt wandered this wild region in 1800 and wrote in his

Travels in the Equinox Regions of the New Continent

:

The first view of the Llanos fills the soul with a feeling of infinity and through this feeling destroys any sensibilities of space, moving the intellect into higher realms. In the same instance there is the impression of clear surface—dead and rigid—like a desolate planet. Equal in size to the central portion of the Sahara it appears at times like the sea of sand in Libya and another time like the green pastures of the Central Asian steppes…. One becomes weary below the endless open sky…the contemplation of the horizon that continually appears to retreat from us; one loses hope of ever reaching anywhere.

Little has been done to tame and cultivate the Llanos. Cattle ranches—some the size of the Florida Everglades—offer the only real source of livelihood for the

llaneros

. But these cattle are not the docile, udderbound creatures of home; they are wild and ferocious, making the life of the

llanero

cowboy an arduous and adventure-filled existence. Real Wild West stuff (before the West was Hollywood-hyped and Roy Rogered into a Saturday afternoon popcorn pastime).

So Gallegos met this true grit-and-guile

llanero

somewhere on the edge of the strange wilderness. And he listened to his tales—tales of midnight roundups (the cattle are too clever to be caught during the day); legends of the “black gods,” “Evil Eye” indians, and the

brujos

(sorcerers); epics of family blood feuds among the regal ranch owners. Murder, mayhem, magic, mosquitoes, mystery, and misery. All the great themes of a great novel. Life on an outback that most people never knew existed. A place where property was the pillar of power and law was whatever the

llanero

barons said it was.

But there was something missing. And Gallegos kept listening.

Then came the story of Doña Barbara.

Now, here was the key ingredient to a truly enduring novel of Venezuelan history. A woman—a woman landowner in a time of total patriarchal domination. A woman who could corral cattle and break in horses better than any man. A woman without scruples who could eradicate anyone who stood in the way of her aggressive ambitions to own all of the Llanos and everything in it—the great rivers teeming with anacondas, alligators, stingrays, electric eels, and deadly piranhas; the endless grasslands and jungle

matas

, where the birds nested and the cattle hid; the vast marshes and quicksand bogs, where antagonists could easily be dispatched to early graves.

Doña Barbara. A nineteenth-century queen of the Llanos. A maven of magic and the black arts. A woman. A witch.

Gallegos worked like a madman. Discarding previous manuscripts, he threw himself into research and romantic speculations. He gleaned every nuance, cajoled ranchers into revealing their fears and fantasies (Doña Barbara was a striking woman and not averse to using beauty and bed to accomplish her schemes), and struggled to separate myth from mundanity.

Writing day and night, he had his manuscript ready in twenty-eight days. Publishers tumbled over themselves to meet his price. It was printed in 1929 in Spain, gained immediate fame and awards, and was eventually translated into twenty languages. Gallegos rode the crest of international celebrity for the rest of his life. Doña Barbara was raised to the level of legend and the Llanos with her. The

llaneros—

previously dismissed as uneducated, untamed wild men—became the stuff of South American machismo and manliness. A nation found its new heroes of the free life—an anarchistic celebration of the unchecked human spirit, male and female.

After reading Gallegos’s

Doña Barbara

, I had to come to the Llanos. Still a “lost world” even today, the place drew me in like a mosquito to hot flesh. My other journeys in Venezuela—my search for the hermit of the Andean Tisure Valley, my struggles in the tepuis of the Gran Sabana—were all wonderful adventures, but I knew that one day I’d enter the Llanos and lose myself in its hazy horizons. And if luck stuck with me, I’d return with something special, something unique. Like Gallegos, I was lured by its legends and—like others before me—I was fascinated by the cruel, sensual, enduring spirit of Doña Barbara.

The truck pitched and bucked like a wild stallion on the rutted earth track. I was in the back with my bags, smothered in dust and screening my eyes from a blazing—and still hot—sunset. It was February, the heart of the dry season. There had been no rains since November. The truck left a trail of spuming dust for a mile back down the track. The driver—an old

centaur

cowboy—was crazy. At least that’s how it seemed. He thought he was back on his horse. He tried to avoid every pothole by riding his vehicle like a bronco. Most times he failed and the poor vehicle cracked and snapped—metal on metal—as the shocks surrendered to the beating and rocks spewed out from under the tires like machine-gun bullets.

There were birds everywhere. Thousands of them. Spoonbills, jaribu storks, white and scarlet ibis, egrets, herons, vultures, and hawks. But asking him to stop so I could photograph them was like trying to slow an avalanche with a bucket. I thumped on the truck roof, but he just leered at me through the grimy rear window and let out some

llanero

howl like a rodeo holler. I gave up. The birds would have to wait. I padded myself in with my bags to keep the blood flowing in my legs and backside. I’d asked to sit in the open back so I could enjoy the sun and the scenery. Only I wasn’t enjoying them much at all.

Somewhere way out there in the burnt-green wilderness was a ranch, Hato la Trinidad de Arauca, of almost one hundred thousand acres. Modest by Llanos standards, but still pretty big. I’d made arrangements to stay here for a while with the Estrada family who had recently opened a lodge as a place of refuge for weary explorers. The Estradas have been

llaneros

for five generations and are hoping to raise capital to keep their cattle land in a natural state, uncultivated and undeveloped. Other ranchers are constantly planning elaborate schemes for farming the rich earth and domesticating their herds of wild cattle, but Hugo Estrada and his family believe the Llanos is far too important as a breeding ground and safe haven for endangered wildlife to be changed.

But there is more to Hugo Estrada’s ambitions than environmental philanthropy. There is the memory—the presence—of Francisca Vazquez de Carrillo, the notorious Doña Barbara. Her ranch, Mata de Totumo, adjoined the Estrada ranch, and her reputation as a sorcerer kept most

llaneros

well away from its dark jungly hummocks and deadly quicksands. They called it El Miedo, The Fear. Legends abounded about the place: ghosts of Doña Barbara’s outcast lovers who haunted the creeks and sloughs, seeking to fill “the eternal holes in their souls” a wizardly “partner” she called “Socio,” who helped her maintain her mastery of the black arts; fierce cutthroat compatriots whose duty it was to seize land, cattle, and property without regard to such incidentals as deeds and laws; strange rituals and sacrifices undertaken in her “conjuring room” to preserve her powers—and always the growing size and wealth of her ranch as she amassed land and cattle using every device in her devious, and deadly, arsenal.

So this is where I was heading, to the

campamento

of Doña Barbara, to meet the modern-day Estradas. And I hoped it was going to be worth all this banging about and dust chewing in the back of a beaten-up truck.

On the way down I had paused in the sweltering little cow town of Mantecal on the edge of the southern Llanos. It happened to be carnival time, a pre-Lent bacchanal of parades and costumed children. (Dressing up like a Llanos jaguar seemed to be very popular.) Everyone was out in the streets, dancing, cheering, and whooping it up near the iron-railed enclosure where the

llaneros

held their regular

toros coleados

rodeos. These were supposedly crazy affairs—cowboys competed to throw angry bulls by their tails. I would have loved to photograph one of these unique events but instead had my cameras and recording equipment almost ruined by a sudden dousing from buckets of cold water thrown by laughing revelers. No one had warned me that one of the highlights of

carnivale

was to go around soaking unsuspecting victims. I was obviously an ideal candidate and left the merry little town dripping and cursing and trying to dry out all the sensitive electronics of my equipment.

The sun had gone now. We were far from the madness of Mantecal. The air had a chill to it, like a desert after dusk. The horizons were muted and vague in the purpling sky. Mystery crept in. I remembered a passage from the Gallegos book:

The Llanos is at once lovely and fearful. It holds, side by side, beautiful life and hideous death. The Plain frightens, but the fear which the plain inspires is not the terror which chills the heart; it is hot, like the wind sweeping over the immeasurable solitude, like the fever lying in the marshes. The plain crazes; and the madness of a man living in the wide lawless land leads him to remain a Plainsman forever. There is madness in the languid desolation—the unbroken horizon enclosing nothing but emptiness—a sprawling wilderness land of struggle and peril, with as many horizons as hopes.

But one man had apparently been unmoved by all the maudlin tales of mystery. Don José Natalio Utreva, head of the Estrada family in the late 1800s, admired the courage and fortitude of Doña Barbara. He knew the power of legend and myth over the lawless

llaneros

. He understood that the only way that Doña Barbara could hope to survive in that harsh wilderness was by determination. She was proud, and clever—but not the evil witch others claimed her to be.

They were close—how close is not recorded. They called each other

pariente

(relative) and they became compatriots in the endless plots and ploys of the ranchers. When Doña Barbara disappeared in 1922—or died (after Gallegos’s book it was hard to separate fact from fiction)—the Estradas purchased much of her land, and her memory—her presence—has been protected down through the generations. Today, on the Estrada ranch, there is a memorial to her, shaded by a great divi-divi tree; her adobe and thatch house has been rebuilt by members of the family and furnished simply in traditional nineteenth-century

llaneros

fashion.

We arrived well after dark after more hours of bumping and banging in the back of the truck. There were stars everywhere, new unfamiliar patterns. As the driver switched off the engine the silence hummed, broken only by the ear-itching saw of the cicadas. Fifty yards away was the Doña Barbara Lodge, built originally by the Estradas for their Llanos ranch hands. Lights shone outside the small rooms. After hours of crashing through the wilderness, seeing nothing but brown-green horizons, the place looked like a palace. I rose up from the truck bed like a dust-coated apparition, then promptly fell down again. My legs were numb. They had forgotten how to stand.