Lottie Project (27 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

Jamie read my letter over my shoulder (I let him because I was trying so hard to be a new sweet person) and he cracked up laughing.

‘That’s a merry sound, James – but a little inappropriate in a classroom,’ said Miss Beckworth. ‘Please tell me why you’re laughing.’

Jamie had long since stopped laughing. He had gone red and stammery. ‘I – I was just clearing my throat, Miss Beckworth,’ he said.

‘I not only have all-seeing eyes, James. I also have all-hearing ears. You were not clearing your throat. You were laughing. Why?’

Jamie shifted desperately on his chair. He’s so weird, he gets so worried the rare times he gets told off. I expected him to blurt out that he’d laughed because of my letter but he kept his lip buttoned to try to keep me out of trouble. Which was sweet of him, but a total waste of time.

Miss Beckworth was looking at me, eyebrows raised, one arm extended. ‘Bring me that piece of paper, Charlotte. How dare you mess around instead of getting on with your set written work.’

‘It

is

my written work, Miss Beckworth,’ I said, taking it out to her.

She read my letter. For one second her lips twitched – and I thought I was going to be OK.

No such luck.

‘This is

not

a formal letter of apology, Charlotte,’ said Miss Beckworth.

‘It

is

– sort of,’ I insisted unwisely. ‘You know what I’m like, Miss Beckworth. I always have to do things my way.’

‘I appreciate that, Charlotte. There is just one small point you seem to have missed. This is my

class

, not yours. In my class we do things

my

way. And you will do me a proper sensible sticking-to-the-rules formal letter of apology now, and you will write out another

five

formal letters of apology, all different, at home tonight. That might make you reflect a little and learn that it makes more sense to do things my way right from the start.’

That was the most amazingly atrocious punishment of all time – especially as I wanted to do something extremely important and very time-consuming that evening. But even I realized it would be unwise to argue further. It seemed utterly unbelievable that such a cruel unbending beastly teacher could have let me cry all over her jumper just yesterday, but there you go.

The one weeny good thing was that she gave me my original letter back, so I could give it to Angela and Lisa at playtime. They laughed too. Lots. And we’re best friends all over again, so at least that’s something.

I got started on my five foul letters the minute I got home. It took me ages but I knew it would be foolish to fudge them. I actually wrote a sixth letter, just a little one.

Dear Miss Beckworth,

This is partly yet another formal letter of apology. I am sorry I mess around at everything. I will truly try to do things your way. Though it will be very very difficult.

This is also an informal letter of thanks. Thank

you

for letting me say all that stupid stuff on Monday. Sorry I used up your tissues! And you were right, because Robin is lots better!

Yours sincerely,

Charlotte

Mark might have made it plain that he wanted nothing to do with me, but he phoned Jo to tell her that Robin’s temperature had gone down, his chest was clear, and the antibiotics were obviously doing their job well.

‘So is Robin properly awake now, sitting up and able to look at things?’ I asked.

‘Yes, but I’m not taking you to the hospital again, no matter what you say,’ said Jo.

‘It’s OK. I can see we can’t go. Mark really hates me now, doesn’t he?’ I said.

‘No, of course he doesn’t. He’s just still terribly wound up and anxious over Robin,’ said Jo.

‘And he blames me.’

‘He wasn’t thinking straight.’

‘Look,

I

blame me. But it’s just sort of weird. Being hated by someone.’

‘He doesn’t hate you, I keep saying that. And anyway, it doesn’t even matter if he does because you don’t have to see him ever again. He probably won’t want me to work for him any more, let alone . . .’ Jo’s voice tailed away. She looked so miserable I couldn’t bear it.

‘Jo? I’m sorry I’ve mucked things up for you and him,’ I mumbled.

Jo gave me a push. ‘What rubbish! You’re not the slightest bit sorry about that, Charlie! You did your level best to spoil things right from the start. And I don’t know why you’re carrying on about Mark not liking you, because you made it amazingly plain that you hated him.’

‘Yes, I know. I couldn’t stand it when he smarmed all over me, and kept trying to take my side. But now . . . I still don’t like him but I want him to like me.’

‘That’s just typical of you, you spoilt brat,’ said Jo. ‘Have you finished all your letters? Shall we go to bed and watch telly for a bit?’

‘

You’re

the one that spoilt me! Not that I blame you, of course. Seeing as I’m so chock full of charm.’

‘Ha! Come on, I can’t be too late. I daren’t mess them about at the supermarket after missing my Monday shift.’

‘I want to do a bit of drawing first. You go. I promise I won’t wake you if you go to sleep first, I’ll creep in ever so quietly.’

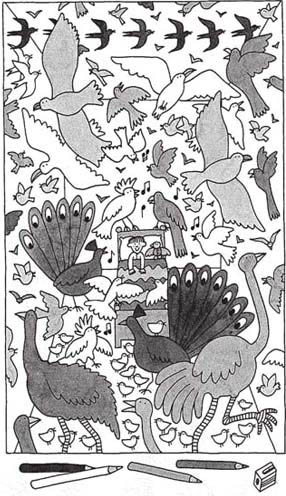

I sat up for hours doing my drawing. I drew a bed in the middle of the page, with a pale little boy and a tiny toy bird propped up on the pillows. Then in all the rest of the space I did an immense flock of birds come to wish Robin and Birdie better. I did great eagles and albatrosses swooping round the ceiling, parrots and cockatoos and canaries singing silly songs, soft doves fanning him with their feathers, lovebirds billing and cooing above his head, tiny wrens whizzing every which way while swallows

flitted

in strict formation, ostriches and emus picking their way cautiously across the polished floor, little fluffy chicks cheeping in clumps, proud peacocks spreading their tails as screens around the bed.

I coloured it all in as carefully as I could, until my

eyes

watered and my hand ached. But it was done at long last – and I just hoped Robin would like it.

Jo came rushing in to tell me

she

liked it at half past five in the morning.

‘Hey! I didn’t wake you up last night,’ I grumbled under the covers. ‘Can you stick it in an envelope and post it to Robin at the hospital?’

Jo said she would – but when I got home from school that day she told me she’d taken it to the hospital herself.

‘It would have spoilt it, folding it all up to fit into an envelope. So I took it to the hospital after I’d been to the Rosens’. I was just going to give it to one of the nurses but then I bumped into Mark quite by chance . . .’

‘Oh yeah!’

‘What are you looking at me like that for? Anyway, he seemed quite happy about me having a peep at Robin, and he’s doing wonderfully. They think he can come out of hospital by the end of the week. And I showed him your picture and he just loves it, Charlie; he spent ages and ages looking at all the different birds and now he’s got it pinned up on the wall beside his bed. Mark was so pleased. He looks a bit better himself now that Robin’s recovering. He’s taken the next week off his work too, and he’s talking about taking Robin to the seaside.’

‘With Robin’s mum?’

‘Ah. No. She’s had to go back to Manchester – when she knew Robin was going to be all right.’

‘Has that upset him?’

‘Well. He obviously misses his mother a great deal, but Mark was always the one who looked after him most even when they were together.’

‘She looked a right cow to me,’ I said.

‘Charlie!’ said Jo. But she looked pleased.

‘What about Mark? Does he miss her too?’

‘Well . . . He doesn’t seem to, no. He said things were never very good between them, and they had all these rows—’

‘Yeah, listen and proceed cautiously, Josephine!

That’s

what marriage is all about. Rows,’ I said, wagging my finger at her. ‘Don’t you dare think of ever getting married, right?’

I did another picture for Robin that night. This time I drew him in a warm red woolly jumper with a pair of massive feathery wings sticking out the back, brown to match his trousers, real robin colours, and he and Birdie were flying over the sea with a flock of seagulls, and they all had sticks of rock or candy-floss or portions of fish and chips in their beaks and way down below there was a beach and everyone was waving and pointing and smiling up at them.