Lottie Project (5 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

‘

Tell

me, go on. You’re scaring me,’ I said, giving her shoulder a little shake.

I could feel she was shivering even though it was hot in the flat and she hadn’t bothered to open any of the windows when she came in.

‘Jo?’ I sat down properly beside her and put my arm right round her.

She gave a little stifled sound and then tears started dribbling down her face.

‘It can’t be that bad, whatever it is,’ I said desperately. ‘We’ve still got each other and our flat and—’

‘We haven’t!’ Jo sobbed. ‘Well, we’ve got each other. But we won’t be able to keep the flat. Because I’ve lost my job.’

‘What? But that’s ridiculous! You’re great at your job. They think the world of you. How could they get rid of you? Was this the area manager? Is he crazy?’

‘He’s lost his job too. We all have. The firm’s closing down. We all knew things had been a bit tight recently, and some of the smaller shops closed, but no-one thought . . . They’ve just gone bust, Charlie. They can’t find a buyer so that’s it. They’ve ordered us to lock up all the shops. I’m out of a job.’

‘Well . . . you’ll get another one. Easy-peasy, simple-pimple,’ I said.

‘I wish you wouldn’t keep saying that,’ said Jo, sniffing. ‘It sounds so stupid. And you’re being stupid. How am I going to get another job? All the electrical goods chains are struggling. There’s no jobs going there. I’ve been to the Job Centre. There’s nothing going in retail at all. There’s some office work, but they want all sorts of GCSEs and certificates. Which I haven’t got, have I? I’m the one that’s stupid.’

‘No you’re not,’ I said. Even though she’d just said I was stupid.

‘I should have tried to keep up with my schoolwork. Gone to evening classes,’ Jo wept.

‘You had me.’

‘I could have been catching up these last few years. But I didn’t think I needed to. I was doing so well at work . . .’

‘You’ll get another job, Jo, honest you will. There

must

be shop jobs going somewhere. You’ll get a job easy . . . You’ll get a job, I promise.’

I promised until I was blue in the face but of course we both knew I could turn positively navy but it wouldn’t make any difference.

Jo didn’t come to bed till very late that night and then she didn’t sleep for ages. She tried not to toss and turn but whenever I woke up I knew immediately she was awake. Lying stiff and still, staring up at our crimson ceiling. Only it doesn’t look red at night. It’s black in the dark.

I woke up very early, long before the alarm. At least the ceiling was dimly red now. Jo was properly asleep at last, her hair all sticking up, her mouth slightly open. She had one hand up near her face, clenched in a fist. I propped myself up on one elbow, watching her for a bit, and then I slid out of bed.

Jo won’t let me stick any posters or magazine pictures up in the living room. We’ve got a proper print of a plump lady cuddling her daughter with a white frame to match the walls. I didn’t want to mess up the round red glow of the bedroom but I’ve stuck up heaps and heaps of stuff in the loo. Want to see?

Of course, it’s a bit weird with all these eyes watching you when you go to the toilet. Lisa and Angela always have a giggle about it when they come to my place.

They both like my home a lot. They’ve got much bigger houses but they think mine’s best. They’re thrilled if I ever have one or other of them to stay over. (They have to come separately – and even then Jo has to sleep on the sofa in the living room.)

Angela’s house seems quite small too but that’s just because she’s got a big family, not just brothers and sisters but a granny and an auntie or two. It’s fun at Angela’s house and she’s got a super mum who

laughs

a lot and she cooks amazing food. Angela and I stayed up half Saturday night and got the giggles so bad when we went to bed that we still couldn’t get to sleep for ages. I nearly fell asleep in church. That’s the disadvantage of staying over at Angela’s. We went to church

twice

on Sunday. I might even have had to go

again

in the evening if Jo hadn’t picked me up in time.

Lisa’s got an even bigger home with a huge garden and a swing. We put up this tent in her garden and camped out in it, though I’d have sooner slept in her bedroom which is pink and white and ever so pretty, with special twin beds with pink and white flowery duvets. Lisa’s mum is all pink and white too and she smells very flowery but she isn’t always as soft and gentle as she looks. She nags Lisa about all sorts of stuff. But Lisa’s dad adores her. He calls her his little Lisalot and when he comes home from work he gives her such a big hug he lifts her right off her feet.

Lisa said it must be awful for me not having a dad. I said I didn’t care a bit. And I don’t. I’ve got Jo.

Sometimes Jo and I play this silly game that we’re both male, because we’ve both got funny names. I’m little-boy Charlie and she’s this big gruff funny bloke Jo who’s my dad. We often have games

together

where we muck around and play at being different people. When I was little my favourite game of all was me being Jo and Jo being me, so that I was the mother and got to tell her what to do.

I wandered out of the loo and into the living room and stared at the space on the carpet where Jo had sat yesterday. I felt as if I was the mother now and she was the little kid – but it wasn’t a game.

The minute Jo woke up she said, ‘What are we going to do?’ As if

I

knew.

I felt worried about leaving her at home when I went to school. I kept wondering if she was sitting on the living-room floor again, all hunched up. I was thinking about Jo and her job and our home so much I didn’t listen in lessons and Miss Beckworth got really narked with me. So I acted cheeky and then I was in serious trouble, but I didn’t really mind. That just made things more normal.

Miss Beckworth kept me in at dinner time. She didn’t give me any stupid lines to write out, though. She said I could work on my Victorian project.

Boring boring boring, I thought – but better than lines. And at least I had the book box to myself. I asked for something about Victorian homes.

‘Not a posh house for the rich. What about an ordinary little home for a poor family? Aren’t there any books about that?’

She found me one or two pages, but there wasn’t much. So I made a lot of it up.

HOME

THERE IS NOTHING

for it. I have to leave home.

I love my home very much, although it is only a tumbledown cottage, stifling hot in the summer and bitter cold in winter. The winters have always been the worst. Two little brothers and one infant sister died during the winter months, and Father passed away last February when the snow was thick on the ground.

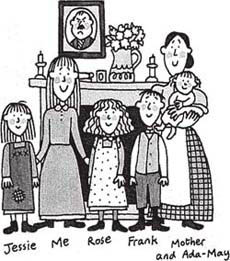

I did not cry when Father died. Perhaps it is wicked to admit this, but I felt relieved. He treated Mother very bad, and though he earned a fair wage he drank a great deal of it. So we were always poor even then, but Mother kept our simple home shining bright. She made bright rag rugs to cover the cold stone flags of the floor and each bed upstairs had a pretty patchwork quilt. I cut out pictures from the illustrated papers and pinned them to the walls. I even pinned pictures out in the privy!

There was always a rabbit stew bubbling on the

black-leaded

range when we came home from school. We’d dig potatoes or carrots or cabbage from the garden, and in the summer Rose and Jessie and I would pick a big bunch of flowers to go in the pink jug Frank won at the fair.

Mother always liked us to wash our hands and say Grace at the table before eating. Father never washed his hands or said Grace, but Mother could do nothing about that. Sometimes Father did not come home until very late. One night last winter he fell coming home in the dark and lay where he was till morning. They carried him home to us and Mother nursed him night and day but the cold got to his chest.

Mother used up her sockful of savings on Father’s funeral. She bought us all a set of black mourning clothes, even little Ada-May. I thought this a waste of money, but Mother is determined that we stay respectable.

Our grandmother and grandfather did not want Mother to marry Father. They thought he was a wastrel, far too fond of the Demon Drink. I privately agreed, but I did not like them saying this to Mother. They came to Father’s funeral and said it all over again. They asked Mother how she was going to manage now.