Louis S. Warren (69 page)

Authors: Buffalo Bill's America: William Cody,the Wild West Show

Tags: #State & Local, #Buffalo Bill, #Entertainers, #West (AK; CA; CO; HI; ID; MT; NV; UT; WY), #Frontier and Pioneer Life - West (U.S.), #Biography, #Adventurers & Explorers, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Fiction, #United States, #General, #Pioneers - West (U.S.), #Historical, #Frontier and Pioneer Life, #Biography & Autobiography, #Pioneers, #West (U.S.), #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, #Entertainers - United States, #History

But even if all the show's Indians were “genuine Indians,” the many questions circulating about what constituted Indian identity enabled its Indian contingent, and the show's impresarios, to play vigorously with Indian authenticity. Show programs portrayed them asâand audiences believed them to beâmembers of separate tribes: Arapaho, Cheyenne, Pawnee, Shoshone, Crow, and Sioux. The reality was far simpler. After early experiments with Pawnees and Wichitas, Cody turned almost exclusively to Oglalas. Thus, each of the show's “tribes” was a group of Lakotas, mostly Oglalas, mounted on horses of a distinct color.

40

We may speculate that Indians used the show for their own ruses, jokes, and impostures. The numerous “chiefs” who appeared with the show were rarely real chiefs, and playing to audience desires for an encounter with the primitive, noble savage must have been as humorous and sometimes perhaps even as rewarding as it could be tiresome.

But in becoming a forum for the creation of Indian identities, the show not only intensified emphasis on certain cultural attributes such as tipis, warbonnets, war-painted horses, and specific dances, but also facilitated acquisition of new skills which became an essential part of modern Indian practice.

In this sense, the ethnic and racial deceptions of the Wild West show were more than an amusement. Although cowboys, Cossacks, Mexicans, and German cuirassiers were not allowed to pass over the race line and assume Indian identities in the performance, Indian performers were allowed and even encouraged to travel in the opposite direction. Luther Standing Bear recalled that his fine regalia took a beating from London fog and soot in 1903. Finally, Johnny Baker, by this time arena director for the show, told him that he should save his best gear for the days when attendance was high, and that on other days “I might take the part of a cowboy if I chose.” “This was a change for me,” recalled Standing Bear, “and I enjoyed it very much.”

41

To judge from extant photographs of the “backstage” showgrounds, Indians frequently put on cowboy gear, particularly hats and the long-haired angora chaps which Buffalo Bill's Wild West made synonymous with “cowboy” prior to 1900. Some were accustomed to these trappings before they joined the show. The advent of the livestock industry on the northern Great Plains led reservation Indians to acquire cattle, and the Oglala and Brulé Lakota owned thousands of animals beginning in the early 1880s. In tending those herds, they enthusiastically borrowed and syncretized cowboy equipment and techniques from Americans the same way Americans had appropriated them from Mexicans. In the last years of the decade, Lakota artist Amos Bad Heart Bull sketched scenes of Indian cowboys at Indian roundups, working in boots, spurs, hats, and even dusters, tending herds that numbered 10,000 in 1885 and 40,000 in 1902.

42

Outside of the Wild West show, Indians' development of an indigenous cowboyhood met with resistance from the same Indian Service officials who championed allotment and railed against Wild West shows. In the popular ideology of progress, after all, cattle herding was a successor to hunting, but it was only a precursor to farming, the foundation on which civilization rested. Thus, one official in Montana warned, “herding leads to a nomadic life,” and “a nomadic life tends to barbarism.”

43

Nevertheless, Sioux cowboys and cattle owners helped generate an Indian cattle industry which lasted almost two generations. Many of the Indians who moved into the show arena after 1900 were experienced cowhands. Indian cowboys worked for ranches off the reservation, too, and many of them moved into rodeo. By 1920, Lakotas such as George Defender and David Blue Thunder were taking first place in competitions against white cowboys, and performing feats of horsemanship from Miles City to Madison Square Garden. As rodeo itself developed partly from Wild West show precedent, so, too, did its parallel, Indian rodeo. At the Rosebud Reservation (formerly the Spotted Tail Agency), home to most of the nation's Brulé Sioux, the earliest Indian rodeos closely resembled Wild West shows; a six-day affair in 1897 included races, bronco riding, steer riding, and a reenactment of Custer's Last Stand, “Mixed Bloods Against Full Bloods.”

44

Thus, Indians appropriated the racial symbolism of the Wild West show for their own purposes, andâin ways that remind us again of Vine Deloria, Jr.'s contention about the show as educational space for IndiansâBuffalo Bill provided a kind of undercover arena in which Indians could acquire and demonstrate cowboy skills, even “out-cowboying” the show's cowboys by dressing in cowboy clothes and performing their stunts as well as they did.

At Pine Ridge, the reservation livestock industry finally fell victim to government hostility, the leasing of Indian lands to non-Indian cattlemen, and allotment, which broke up many of the finest range lands. Lakota cattlemen sold their last large herd in 1917.

45

As a major employer at Pine Ridge from 1886 until 1916, Buffalo Bill's Wild West show overlapped almost perfectly with the reservation's cattle industry. Until its very end, cattle raising seemed one of the best hopes for a prosperous Lakota future. The Wild West show offered a means of integrating cowboy culture and Lakota culture.

Back at the reservation, show wages paid for cattle and horses, as well as wagons, farm tools, and other necessities. As early as 1892, agents at Pine Ridge were complaining about small amounts of money from Buffalo Bill's Indiansâ$5 and $10 sums in greenbacksâwhich arrived at the Indian office with letters “in Indian” informing the agency which friends or relatives should receive the money, and in what denominations. Fast Thunder, one of the Wild West show's Indian contingent, was said to have acquired four thousand cattle by 1896, and a comfortable cabin with “splendid” farm fields.

46

Less wealthy Indians in the show routinely sent money home, too.

47

Indians in the show augmented their wages by selling Indian crafts, especially “ âbead work' made into moccasins, purses, etc.,” for which they received “very large prices,” according to Nate Salsbury. There was a market for Indian crafts on the reservation, but it appears to have flourished in the Indian camp at the Wild West show, because of the connections Indians built with non-Indian suppliers and customers. Cody and Salsbury bought materials such as brass beads at wholesale prices, and sold them at cost to show Indians, who made them into souvenirs for sale to tourists and kept the profits for themselves.

48

Men profited handsomely from this trade.

49

But beadwork and moccasin manufacture were traditionally women's occupations, and it appears that Indian women in the show exploited the market for Sioux crafts assiduously. This might explain why Calls the Name, the sister of No Neck (chief of the show contingent in the 1891â92 season), had $260 in cash and goods during that year, after receiving only $112 in salary from Cody and Salsbury.

50

If Calls the Name's experience is any guide, Indians manufactured and sold Indian crafts to museums and collectors across Europe. Calls the Name sold some of her goods to the show's translator, George Crager, and perhaps used him as an intermediary with outside purchasers. Early in 1892, Crager approached the Kelvin Grove Museum in Glasgow about selling his “collection of Indian Relics.” Among the goods he sold were a pair of buckskin leggings embroidered with beads, which he claimed had been worn by Calls the Name in 1876, the year of the Little Big Horn fight. In reality, they were probably of recent vintage. Some of the other materials Crager peddled, including a pair of moccasins embroidered with brass beads and a shield that is of minimal craftsmanship, are on display today in the Kelvin Grove Museum, and they appear to have been products of the show's Indian craft industry.

51

In all likelihood, Indians commissioned Crager as their sales agent, to sell the goods to the museum and return at least some of the cash to their Indian manufacturers. But Crager was a publicity hound. (He finagled his way into the show by translating for the show's detractors, including James O'Beirne, in the controversy that engulfed the show in 1890.) When he discovered that his name would not be preserved as a museum “donor” unless he gave at least some of the goods away, he quickly did so.

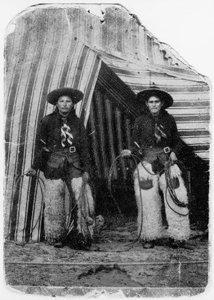

Wild West Indians/cowboys,

1909. Indians sometimes disguised

themselves as white cowboys in the show, allowing white spectatorsto claim Indian riding skills as a white racial characteristic,

and giving Indian performers a chance to display cowboy techniquesthey used to tend growing cattle herds at home. Courtesy

Buffalo Bill Historical Center.

Such maneuvering likely helped Crager earn a poor reputation among the Lakota. In late December 1892, Charging Thunder, a Lakota man in the show's Indian contingent, clubbed George Crager over the head backstage, knocking the translator out cold. Charging Thunder apologized, blaming the fight on whiskey which some publican allegedly slipped into the lemonade he ordered. But given the variety of goods Crager hawked to the museum, and his dubious reputation, it appears likely that tensions over Crager's sale of goods contributed to Charging Thunder's ire. In any case, Charging Thunder spent thirty days in a Scottish jail as a result.

52

Crager left the show after one season, and returned to Pine Ridge, where he joined the staff of the Indian agency.

53

AT THE END of each show season, Buffalo Bill's Wild West provided a letter of recommendation for every performer. Cowboys who learned performance arts in Buffalo Bill's Wild West show frequently went into western films, other Wild West shows, and rodeo. As we have seen, here was always a wide streak of performance art in cowboys, who strove to approximate their romantic fictional counterparts even in the days of the Long Drive from Texas to Kansas. But over time cowboy skills became so oriented to entertainment that by the Wild West show's final years, around World War I, at least some riders came to Cody's show having learned their skills not on the range but in circuses and other entertainments. Those who wanted to remain cowboys found that the best living was to be had in performing the identity for somebody else, rather than living it on the range.

Meanwhile, show wages grew in importance for Indians, who had less room than cowboys to maneuver into other occupations. For a brief time after the disaster at Wounded Knee, the army ensured the Lakota their full rations, but discounting and punitive withholding soon began anew. By 1900, rations were only about 70 percent of their stipulated treaty levels, amounting to one pound of beef and 5.75 ounces of flour per person, per day. In 1902, the government announced a plan to eliminate rations for all “able-bodied men,” the better to force them to work for $1.25 per day, usually at hard manual labor, such as fence building, road grading, or dam construction.

54

By the end of the summer, wrote Luther Standing Bear, “The Indians were all heavily in debt to the storekeeper.”

55

These conditions drove Luther Standing Bear to join the Wild West show that very year. Others who joined the show in this period were similarly motivated, and some of them used the show to advance their ongoing political battle with the Office of Indian Affairs. In 1908, three Lakota men with Buffalo Bill's Wild WestâBad Cob, Edward Brown, and William Brownâtook time between shows in New York for an angry meeting with the commissioner of Indian affairs. Bad Cob complained that the agency interpreter, a Lakota, was holding two salaried jobs which could better be given to two different men. The Browns were particularly confrontational, and their grievances reflected the frustration of educated Lakota men. William Brown was a graduate of Carlisle, and Edward, too, was a school graduate. Edward “said that he is anxious for any kind of job whereby he can earn a living, and that he believes that there are enough returned students on the Pine Ridge Reservation to do a good deal of the work which is now done for the Government by white persons, and wanted to know why the returned students are not given this chance to get ahead.” William Brown pointed out that even the lowest-paid work was unavailable to him. Why couldn't he get road work on the reservation? Why couldn't he be an assistant farmer? The Browns and Bad Cob, reported the commissioner, “were very insistent on these matters.”

56

Such complaints were not new, but Indian office functionaries customarily read them in letters or heard them from third parties, not from the Indians themselves, and certainly not in New York, hundreds of miles from Pine Ridge. However startling it was for the commissioner of Indian affairs in 1908, Indian use of the show as a means to confront policymakers was not new. Show performers' geographic and social mobility had been influencing Sioux politics for a generation. In 1885, Sitting Bull had used his tenure with the Wild West show to cultivate relationships with whites he would not meet otherwise. In 1887, Lakota performers discoursed late into the night on the significance of their meeting with Queen Victoria. After this all-night discussion, “every one of his young men resolved that she should be their great white mother.”