Love by the Morning Star (31 page)

Read Love by the Morning Star Online

Authors: Laura L. Sullivan

“You are,” Lord Liripip said. “But in any event, the whole thing is being hushed up. The monarchy can't afford to look vulnerable just now. It's happening, you know. Tomorrow or the next day His Majesty will make the announcement. We will be at war.” He tottered off to examine some withering ferns.

“If she hadn't lied, we might not have fallen in love,” Hannah said when she and Teddy were more or less alone.

“I would have loved you no matter what,” Teddy said, nuzzling her cheek. “Even if my mother approved of you, I would have loved you, though it would have been very hard.”

“I hope your mother is feeling better soon,” Hannah said, doing her best to sound sincere. Lady Liripip had followed Anna's example, but regrettably everyone's attention was on the young people and no one happened to notice and catch her. The doctor said she'd broken her collarbone and would have to keep to bed for weeks. (Actually, he'd first said she's bruised her collarbone and ought to be careful for a day or two, but after a charitable donation from Lord Liripip he amended his diagnosis and prescription drastically.)

“What Anna did was not so bad,” Hannah mused, snuggling comfortably under Teddy's arm. There was just enough light to see each other's faces.

“She stole your life and tried to kill her king!”

“In one way,” Hannah said slowly, putting her thoughts together. “But she didn't lie, exactly, did she? Not at first, any more than I did. I showed up and they thought I was one person and I accepted it. She showed up and they thought she was quite another person and she accepted it. Then we both filled in the details to stay in our places. We each were where we thought we deserved to be. You must admit, she makes a much more convincing daughter of an English aristocrat than I do.”

“Stuff and nonsense,” said Lord Liripip, limping out of the gloom. “I know quality when I see it, and you, my girl, are it.”

“With respect, sir, you thought I was a floozy.”

“But a

quality

floozy, my dear,” he said with a rakish wink that he'd been saving for twenty years.

W

AR CAME ON

S

EPTEMBER THIRD

, and with it the impossibility of receiving any letters from Germany. It was very hard for Hannah to be happy, but despite the uncertainty of her parents' safety, she wasâblissfully happy, and terribly guilty.

“But I won't marry you until I know they're safe,” she insisted to Teddy.

She might have been persuaded if Teddy had to go to Germany, either as soldier or spy, but after the engagement debacle, when Hannah in her deeply injured wrath had spoken openly of Teddy's spy work, all that was nixed. A furious telegram had come from Burroughs after a paragraph appeared in the next morning's gossip column. All that work wasted on a spy who was outed before his mission began! When Teddy wanted to enlist, Burroughs told him not to be a fool. He was far more valuable at home managing other spies in the ranks of the Special Operations Executive than volunteering to be cannon fodder.

So Teddy, seeing all of his friends join up, and half of them killed in the first year while he stayed safe at home, had a burden of guilt all his own.

Â

T

HE FIRST LETTER CAME IN

the summer of 1940, via the Red Cross.

Â

Darling Hannah

,

I'm having the most jolly time as a prisoner of war. No, the guard looking over my shoulder to censor any dangerous bits points out that soldiers are prisoners of war, while mere civilians such as I are internees. In any event, I find myself in a most wretched place called Tost, in Upper Silesia. (My censor says I may say the name of the town. I suppose you might tell any RAF boys you happen to meet not to bomb it.) To my delight, the population is predominantly male. Apparently I was sent here because of a clerical error, and it would be too much trouble to remove me at this point, so here I stay

.

You'll never, ever guess who is here with me, at this very moment, sitting at the next camp table and looking hungrily at my fresh paper supply. Old Plum himself! Mr. Pelham Grenville Wodehouse! Apparently he and wee wifie were in France when it was invaded and they refused to leave their little dog, so they were snatched up. Wifie is in Paris, Plum is here, and the poor dog is probably eaten by now, for I've heard there are grim food shortages in France, and everywhere else too

.

(Here my censor insists that everyone under the Reich eats like a king. Perhaps the Reich has not yet found Tost, for we live mostly on potatoes and rumors.)

Poor Plum! He is such a charming innocent, and I fear he will catch it after the war. He's so chummy with everyone, friend and foe alike. I personally keep a certain frosty distance between my captors and myself, as I am still technically English. Only occasionally do I accept chocolate or lipstick from an officer. Then I barter them for paper for Plum. I dare not eat chocolate. The perpetual potatoes have gone straight to my hips. Your papa will not know me when he sees me again

.

I am well, though unutterably bored in this dreary place. What a dump! I had never even heard of Upper Silesia before, and now I know why. I told Plum, if this is Upper Silesia, I'd hate to see Lower Silesia. He said he will steal that for his next book. So you see, there are bright spots. My quips will be immortalized. I must be like Plum, and not see problems and enemies, but people and opportunities. He's like a puppy, endlessly optimistic. You must be like a puppy too, love. Be happy, for all is well

.

Write to me, beloved girl

.

Cora

Â

“He's alive!” Hannah said, beaming through tears as she handed the letter to Teddy. “My father is alive!”

Teddy held her hand as he read through the note, absently stroking the little scar. “She doesn't say so,” he began uncertainly.

“Oh, no one says anything outright in wartime. But look hereâhe won't know her when he sees her again. That means she's sure he

will

see her again! And hereâall is well. She's afraid to give any details for some reason, but she believes he's perfectly safe. And if she believes it, I believe it.” Hannah flung her arms around Teddy.

Â

T

HE SECOND LETTER CAME AT

the end of that year, when Starkers had just thrown open its doors to a herd of Cockney urchins sent to escape the Blitz. It had a California postmark and positively reeked of sunshine.

Â

Liebchen

,

Siberia is not all it's cracked up to be, so I'm giving California a try

.

There's a fellow here, Preston Sturges, who makes the funniest films that just can't seem to get past the Hollywood morality police. I talked Pres into letting me tackle a rewrite of a flick called The Lady Eve, and now I have a real studio jobâI write sex scenes so no one can be sure whether the lovers have actually had sex. Still the same tricky old Teufel, you see, in the same funny old world

.

Write so I know you're still safe at Starkers. Maybe the Yanks will step in and hurry this damned war along. Out here, though, most of them don't seem to notice

.

All of my love, dear heart

,

Aaron

Â

Much later Hannah learned of her father's harrowing journey to Russia, of the golden promises and black betrayals that country offered . . . of the midnight escape, crossing the Pacific curled up in a bulkhead . . . of destitution in the golden land of oranges and sunshine . . . of his work as a shoe shiner . . . how an offhand quip about polishing shoes shiny enough to see up a lady's skirt led to a stellar Hollywood career as script doctor, then writer, then director, with a gracefully aging Cora Pearl as his star . . .

But now, her happiness complete, Hannah consented to be married in a fortnight.

“Over my dead body!” said Lady Liripip, who had spent the last year campaigning against her son's intended. Good to her word, she died the morning of their wedding. No one noticed for hours; her stiff posture and rigid smile were nothing unusual. In fact, everyone was impressed by her remarkably pleasant behavior.

When she was discovered, the family shed a few obligatory tears, and Hannah placed another order with the florist who had served them so ably at their wedding.

“Hannah, is that you?” squealed the voice over the phone line. “Lilies? She did? Cor! How very thoughtful of her. No, no calla lilies in stock, can't abide them, but I have heaps of lovely white stargazers. I'll make up a few wreaths, and maybe some big pots of mums. Ha! I don't imagine she invited you to call

her

mum, did she? Of course not. Condolences and whatnot, but it is for the best, I believe. Oh, I'll send you a spray of lemon blossoms too, just for you, luv. Is there any welcome news yet? Silly me! That's only a great idiot like myself who walks down the aisle with a big belly. You'll wait your proper nine months, I'm sure. Eight? You devil! Can you hear mine over the wire? He's got a handful of peonies, the terror, tearing them to shreds like they don't cost half a guinea apiece this time of year. Yes, Hardy is splendid. Always away growing his war weeds for the Ministry of Agriculture, but I have the flower shop to keep me occupied. Give my love to Teddy, will you? Not too much, though! Oh, I forgot to tell you last time we talked: Hardy said that his new strain of pigweed is such a success, they're thinking of knighting him. Fancy that! I'll be Lady Anna after all. Ta!”

Â

Â

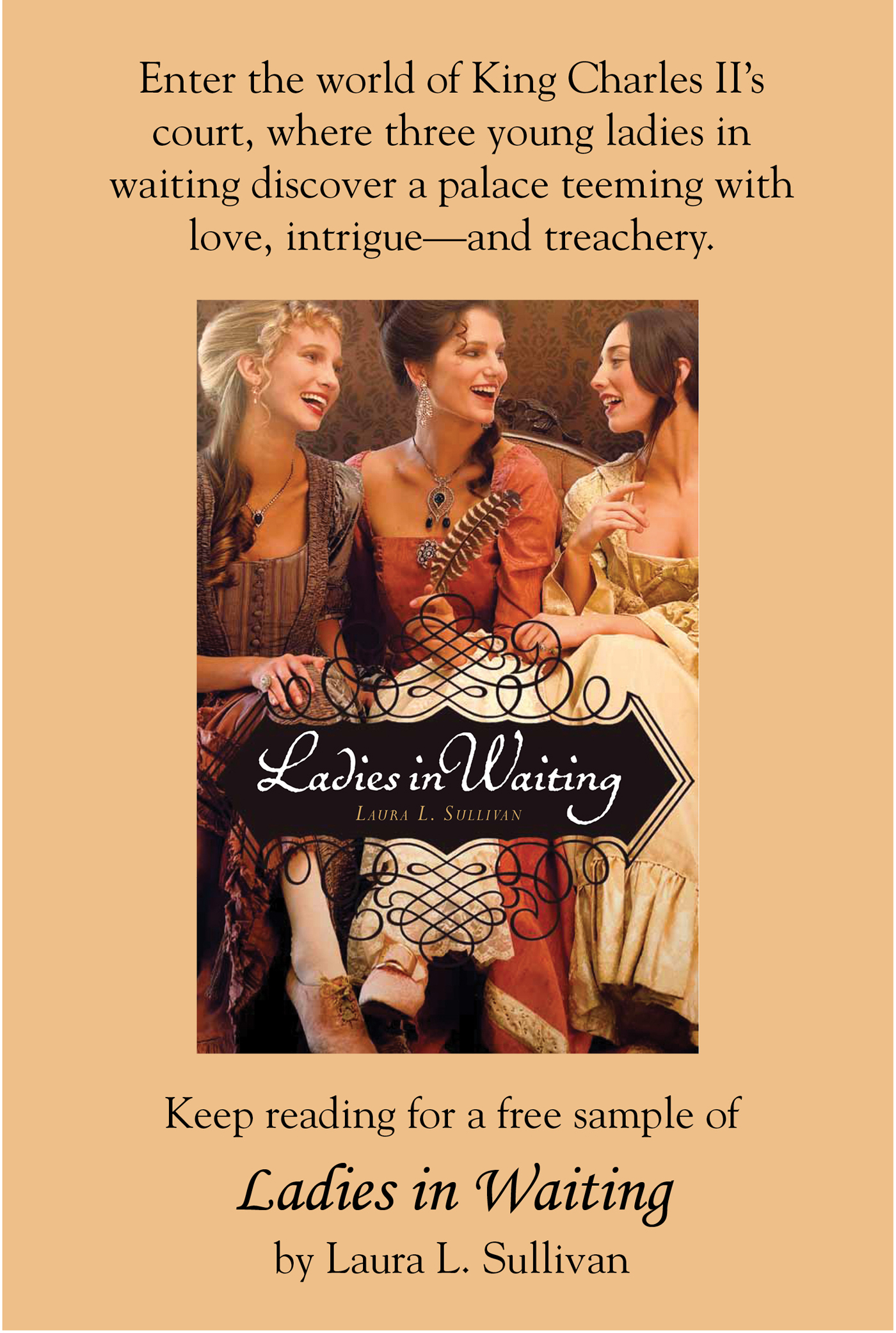

Chapter 1

England, June 1662

Â

E

LIZA PARSLOE

, age fifteen, tickled her chin with her plumed pen and gazed levelly at her latest opponent, Lord Ayelsworth, second Earl of Lambert. To her great displeasure, he took it for flirtation and sidled closer until his foppishly beribboned thigh crushed the delicate moiré of her apricot skirt.

“You slay me with those killing eyes,” he sighed.

Those killing eyes rolled, for she knew he was looking not at her decidedly plain brown orbs, but rather at the fortune in emeralds at her throat, or perhaps, to give him credit as a man of flesh as well as avarice, at the swell of bosom lower down.

Why did each and every suitor feel it necessary to harp upon her nonexistent physical charms? If just one had suggested they could use her vast fortune and his court influence to rule the nation, to set the mode, she might have been swayed. But no, they spoke of her languishing eyes, her enchanting hair; compared her neck to a swan's and her skin to pearls, when she knew full well her only beauty lay in the acres of timber, the flotillas of merchant ships, and the masses of gold settled on her as the only child of the fabulously wealthy Jeremiah Parsloe.

She turned away from him and dipped her quill in the ink, dripping a blob, unnoticed, on her buttercup-colored satin underskirt, and began to scribble.

“What do you write, sweetheart?” Ayelsworth asked, craning his skinny neck to see. “I would pen you a thousand love poems daily, if only you would be mine!”

Eliza dipped the pen again and flicked it as she turned to reply, spattering his multihued ribbons with blue-black. He squealed and leaped up. Eliza instantly kicked up her feet and crossed her ankles, reconquering the lost territory of her chaise.

“It is a play,” she said.

“What do you call it, sweet nymph?”

“

Nunquam Satis

,” she said, and though he had no Latin, he knew the vulgar tongue. He wasn't sure whether to laugh or blush.

“My dear, do you know what that means?”

“âNever satisfied,'” she replied evenly.

“Ah, but in the common cant, it means . . . it means . . .” He could not tell her what part of a woman's anatomy was, by popular jest, never satisfied. She was from a reputedly Puritan family. Very likely she was not even aware of that particular part of herself.

Ayelsworth, though but twenty, was a habitué of Charles II's court, and accustomed to whores, courtesans, and loose ladies of rank. He was not quite sure what to expect from this provincial heiress. All he knew for certain was that she was the catch of the season, and if he could secure her, his future was assured.

Her father had given him permission to try for her hand, leaving them alone with only a maidservant within, for propriety, and a liveried footman without, in case he should try to claim his prize by force. Now, that was a thought, he mused. It had certainly been done before, though mostly through abduction. Still, if he managed to spoil the goods here on the chaise, she and her father would probably agree to let him buy what remained.