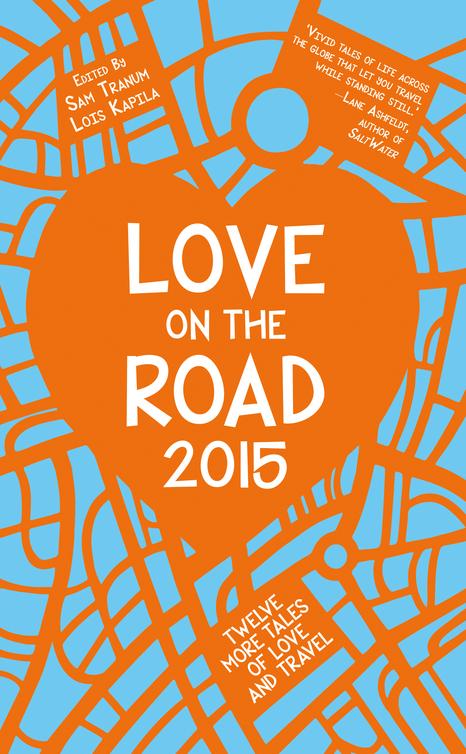

Love on the Road 2015

Read Love on the Road 2015 Online

Authors: Sam Tranum

Twelve More Tales

of Love and Travel

Edited by

Sam Tranum and Lois Kapila

- Title Page

- Foreword

- 1. The Queue

Tendai Huchu - 2. Sunrise over Sausalito

Marlene Olin - 3. Not a Finger More

Shirley Fergenson - 4. Janus: A Path to the Future

Nod Ghosh - 5. Enfolded

Catherine McNamara - 6. We Will Dance in Lampedusa

Stanley Kenani - 7. At the Mouth of the River

Barry Reddin - 8. Manila Envelope

Tendayi Bloom - 9. Kaveh Mirzaee and the Woman from Lashar

Lily Mabura - 10. In the Heat

Jackie Davis Martin - 11. Honeymoon in Mata de Limón

Alice Bingner - 12. Refugees of the Meximo Invasion

Gregory Wolos - About the Authors

- Copyright

This anthology is the product of the Love on the Road writing contest, which we ran between May and July of 2014. In our call for submissions, we asked writers around the world to send us their tales of love and travel, true or imagined.

This is the second time we’ve run the contest. The first iteration, in 2013, resulted in the anthology

Love on the Road 2013: Twelve Tales of Love and Travel.

We enjoyed it so much that we decided to do it again.

This time around, writers sent stories to us from Australia, Belgium, Canada, Italy, India, Ireland, Malawi, New Zealand, the Philippines, the UAE, the UK and the US. We selected our favourite twelve stories, which are published in this anthology. Nod Ghosh’s ‘Janus: A Path to the Future’ is true; the rest are fiction.

We then sent these twelve stories to our panel of judges, who selected the contest winners. First prize went to Shirley Fergenson for ‘Not a Finger More’. Second prize went to Tendayi Bloom for ‘Manila Envelope’. And third prize went to Marlene Olin for ‘Sunrise Over Sausalito’.

We would like to thank the judges: Alexander Cochran, an agent with London’s Conville & Walsh; Amanda Festa, managing editor of Boston’s

Literary Traveler;

Lucas Hunt, director of New York’s Orchard Literary; Jessu John, a Bangalore-based journalist and writer; and Vanessa

O’Loughlin, founder of Irish publishing consultancy The Inkwell Group.

Thanks also to all those who were kind enough to share their writing with us.

—Sam Tranum and Lois Kapila

Dublin, January 2015

The Queue

Tendai Huchu

Tinotenda arrived just after ten in the morning and took his place in line. He knew right away that going on a bender the previous night had been a big mistake. The month end used to be fun. Back in the day, when he did his training, they used to look forward to their monthly cheques. There were fewer zeroes then – hell, he wasn’t even a millionaire – but you got more bang for your buck. His head throbbed and he promised God he would never drink that evil Eagle beer again. All God had to do in return was resume supplies of Castle, or even Lion. Was that too much to ask for? The Israelites got manna, Zimbabweans only wanted beer.

‘Is this the one for the post office?’ he asked the fat man in the Hawaiian shirt in front of him. The blue waves, tropical palms and surfboards were rather curious in a landlocked country.

‘I stood in that one for thirty minutes before I realised it was for bread!’ the fat man replied. A whiff of bad breath hit Tinotenda.

‘So this one is for the post office?’

‘What do you think?’

‘If I knew I wouldn’t be asking you.’

Tinotenda massaged his temples. The fat man turned away in a huff. What was that about? Tinotenda wondered. He studied the cool, hypnotic waves of the shirt and considered whether it was prudent to ask the next man in the queue. It would take some manoeuvring to get around the heap of Hawaiian flesh. A hand tapped his shoulder.

‘

Bhudi

,

is this the queue for the post office?’ a small woman in a georgette dress asked him.

‘I don’t know,’ he replied honestly. ‘It should be. I certainly hope it is.’

The woman raised her eyebrows but she did not say anything. It was not uncommon for people to jump into a queue first and ask questions later. The mid-morning sun pulsed down on them. The tar shimmered under the sun’s oppressive brilliance, creating a mirage like cool water flowing down a stream. There wasn’t a cloud in the sky. A prison lorry ambled along slowly on its way to the magistrates’ court. The prisoners were all dressed in white. Their shaved heads glistened and they became a throng of brown mirrors, dazzling and brilliant. The guards stood at the front, FN rifles resting casually at their sides. The lorry jolted as it hit a pothole and rolled on.

‘Hold my place. I will go up front and ask someone,’ the woman said.

He watched her walk past the fat man, studying her bony frame, swaying hips, elegant gait. The fat man was watching too, nodding his head appreciatively. A man dressed in blue overalls joined the queue and Tinotenda told him there was a woman before him. The man wanted to know if this was the queue for the post office. He would have to wait for the woman. The boutique to their left was almost bare. Still, it

was open, selling pirated cassettes.

Sungura

music blared out, distorted by damaged speakers. It was shrill, with a hiss behind the wailing, depressed electric guitar. The song was a popular one:

Oweoo oweoo oweoo

My brother died

My wife left me

My son is a cripple

I have no other children

My father and mother are dead

Now I am dying.

Who will bury me?

Oweoo oweoo oweoo

And so it goes. Tinotenda fought the pangs from his empty stomach, the feeling of bile rising. The woman returned and took her place in the queue.

‘You’re a teacher aren’t you?’ she asked with a smile.

‘Are we in the right queue?’

‘I noticed the chalk dust on your trousers.’

The man in the overalls was craning forward to hear. She held vital information and was keeping everyone waiting. There was an air of suspense. Others, who’d since joined the queue, also waited on her verdict – right queue or nay. Tinotenda reasoned that she wouldn’t have been in this position of power if the fat man hadn’t been a jackass. This was the Information Age, after all.

‘Yes, I am a teacher. Now please answer my question: a) yes, b) no.’

‘Which school?’ she asked.

‘Oh, for the love of Jesus who died for all our sins!’ the man in overalls cried out.

‘Okay, I’m just joking, this is the right queue,’ she said, a smirk on her face.

There was a collective sigh of relief from the crowd that was growing behind them. They moved three steps forward and stopped again. A small victory against crushing inertia was won in that movement. It was progress. Tinotenda recalled a slogan he taught his pupils: forward ever, backward never.

He thought of changing banks. The Post Office and Savings Bank had been his bank since childhood, but it seemed the service only became slower and worse with the years. He’d stuck with them through the ’90s when the government had floated a bizarre proposal to raid savers’ deposits to fund war veterans’ annuities. They’d decided against that in the end. It was easier just to print the money. Tinotenda felt he would be better off with Standard Chartered, Barclays or even CABS. There were queues in those other banks, yes, but they seemed to move faster. The folks who stood in those queues, as a rule, were better dressed, to the extent of even wearing purposeful looks.

The man in overalls verbally calculated whether he could make the bread queue next. A woman behind him said he would have been better off bringing someone else with him so they could have got places in both queues. She went on to explain that that’s what she’d done, and that she also had a child in the bottle-deposits queue at TM. There was a hint of pride in her voice, as if holding places in three queues simultaneously was a triumph in itself.

I wish I’d got a post in Harare,

Tinotenda thought. He

hated Bindura, its smallness, the old colonial buildings, the slow pace of life, how everyone knew one another. The street-lights seldom worked. ZESA hammered the town with load-shedding but mysteriously maintained power to the mines. That was all there was to the town: a huge gold mine and an even bigger nickel mine. The men in overalls and khakis strutted about the place like they owned it and thumbed their noses at people like him. To them, it seemed being unemployed was a lot more respectable than being a pen-pusher. The little town had one main road that you could walk down, from end to end, in less than a quarter of an hour. Tinotenda wondered how he’d ended up in such a backwater dump.

‘I’m a student you know,’ the woman in the georgette said.

He bowed his head slowly. Even the slightest movement made his brain feel like it was banging against his skull. He was assaulted by Hawaiian blue in front of him, and her dazzling orangey autumn colours from behind.

‘Have you got any Cafemol?’ he asked.

She rummaged through her denim handbag and handed him a pack of Anadin.

‘Thanks,’ he said, taking two and handing the pack back.

The queue inched forward, one more small victory – two, if he counted the tablets. That was the only way to take things these days. It was easy to get caught up in a spiral of despair. The woman was looking at him intently, as if waiting for him to say something else.

‘What are you studying?’ he asked.

‘I’ll give you two guesses.’

‘Look, I’m grateful for the pills, but I’m not really in the mood.’

‘Your eyes are very red.’

She turned away from him and looked down the road to the GG Café, door wide open, shelves empty. Why did they bother opening up? Why did they keep coming to work? Why didn’t everyone just curl up and die quietly? Tinotenda wondered what it was that kept the entire nation going. He saw news reports of starving folk in the rural areas. They reminded him of pictures from Somalia in the early 90s, when he was still at college. In the face of this never-ending misery, there was something, hidden – an elementary particle, fundamental, unknown to science – that said life was still worth clinging on to. The worse things became, the more precious it seemed.

‘We must be mad,’ he said to no one in particular.

‘Depends on how you define madness,’ the woman said to him.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Sithabile – Star, to you.’

‘How can you be so cheerful in this?’ He gestured, his hand making a wide sweep across the bleak street.

Oweoo oweoo oweoo.

‘How can I not be, Mr Teacher? What people don’t understand is the true meaning of queues. They think queues are an inconvenience. A waste of time. But are they? Think of where we would be right now if there was no queue. We’d all be in the post office, scrambling, punching, scratching – survival of the fittest. No, queues are the height of civilisation. The last line of defence against chaos.’

‘It’s this passivity that got us into this situation in the first place.’ Tinotenda watched the fat man let a friend cut in front of him, forcing everyone to take a step back. ‘You see what I’m talking about?’

‘The alternative is so much worse. You forget that at the end of the queue lies hope. That’s what is in your heart right now. The faith that your fellow men will keep their places, despite all provocation, and that at the end of it we will all attain our goal. The queue forces us to put trust in our fellow man.’

‘What are you studying?’

‘Marketing, at the Bindura University.’

‘One day you will be selling positions in queues at the rate you’re going.’

‘I’ll be selling hope,’ she said with a smile, as if she were the teacher, full of infinite patience, speaking to a pupil who just didn’t get it.

An old woman walked by with a reed basket on her head. Tinotenda stopped her and bought two freezits for a few grand. He gave one to Star. She looked surprised and thanked him. He sucked the cold juice and downed his Anadin. Litter tumbled down the road, blown by a gentle wind which mercifully cooled them. Maize cobs, plastic bottles, paper bags, leaves and debris floated by, dancing in the wind as they went.

Cars were lining up on the lane opposite. They were aimed at the Total garage at the T-junction ahead. A tanker had just arrived and was pumping fuel into the tank. The drivers waited patiently, their engines switched off to save precious fuel. A few were on their cell phones, no doubt telling friends there’d been a petrol delivery. A pickup going in the opposite direction spotted this queue, made an abrupt U-turn and joined in. Tinotenda listened to the hum of the tanker. He watched the garage attendants in the shade, chatting with the tanker driver as they watched their new queue grow longer and longer.

The post office was coming into view now. It was a small, cream-coloured colonial building with a red-tiled roof. Standing in the middle of the town, it flew a multi-coloured Zimbabwean flag alongside a blue one for the postal service. The flags fluttered in the wind. To Tinotenda’s dismay, a guard in green overalls and a green hard hat stepped out.

‘It’s lunch hour,’ the guard announced.

He used his baton to separate those who were inside from those at the entrance and shut the doors.

‘Unbelievable,’ said Tinotenda.

‘Well, they have to eat something too, don’t they?’ Star said.

‘I’m not saying they shouldn’t have a break. But wouldn’t it make more sense for them to stagger their breaks so service isn’t disrupted?’

‘Isn’t it better for them to eat together, like a family?’ Star was unconcerned. It was as if she hadn’t a care in the world. Tinotenda decided she was young and she hadn’t seen a world before this one. This abnormality was her version of normal, and so she accepted it.

‘What are we going to do with our lunch hour?’ He couldn’t mask the sarcasm in his voice.

Tinotenda sat down on the pavement. He leant his back against the wrought-iron burglar bars of Sales House. He turned and saw a few outfits inside, and staff looking forlornly outside. He used to shop in there, back in the day. He had an account at Edgars too. When did he last buy new clothes? Thank goodness for the flea market, with its bales of used American clothes, donated, now on sale.

Across the road, he watched the queue of vehicles move forward – making progress. He’d long since stopped dreaming of ever owning a car. He was pushing thirty, around that

age one begins to make peace with the world, worn down by years of compromise and dreams that have turned to nought. It was now clear to him that a roof over his head and at least one square meal a day was all he could ever ask for. A pickup with a Trojan Horse, the mine’s logo, was bumper to bumper with a blue Toyota Cressida. The driver of the pickup was his age, square-jawed and confident.

The Anadins were kicking in. The headache eased off. The sun had drifted overhead, so they were now in the shade of the shop verandas. Flakes of peeling paint rained down like snow from the asbestos roofing sheets.

Oweoo oweoo oweoo.

An old Peugeot 405 coughed up acrid black smoke as it inched forward. Beads of sweat formed on Tinotenda’s face. He took slow breaths and waited. It reminded him of the last election. He’d queued all day to vote. Within a week he had learnt that his vote had not counted. It had changed nothing. Every time he was in a queue, he could not help thinking that the whole country was waiting, waiting for something. But each queue only led to the next and the next and the next – an infinity of queues stretching out through space and time.

They heard the old doors of the post office creak open. Slowly, they stood and faced forward once more. The feeling that he was making progress returned as they shuffled a few steps forward. Tinotenda tried to gauge the distance to the doors against the speed they’d been moving at and calculated that he was going to make it. A woman walked by carrying a bundle of firewood on her head. With one hand, she cradled a baby, who suckled on her left breast, which was poking out through her torn blouse. With the other, she carried a gallon of cooking oil. People walked to and fro. The town was always packed at the end of the month.

‘What do you want to do when you finish uni?’ he asked Star.

‘Anything, the world is my oyster.’

‘You’re kidding right?’

‘Why should I be? There are opportunities here. Most people just don’t see them because they’re locked up in their self-pity. I mean look at us right now. All these people in a queue to get money. If I stood in front of the post office with the right product, I’d take all their money away in a heartbeat.’