Lucy Doesn't Wear Pink (14 page)

Read Lucy Doesn't Wear Pink Online

Authors: Nancy Rue

Tags: #Christian, #Juvenile Fiction, #General, #Religious, #Sports & Recreation, #Social Science, #ebook, #book, #Handicapped, #Soccer

“I don’t have a computer.”

Mora flattened her palm against her forehead. “I can’t even deal with this another minute.”

And definitely not for two months, if Lucy had anything to do with it. She tried to put some hope in that as she sank her teeth into a quesadilla.

Inez cooked dinner before she left — pork asada, she called it, and salad and black beans that Lucy refused to admit were the yummiest things she’d ever put in her mouth. She’d seen how many chiles Inez had put in the salsa, though, and she gave that a wide margin at the dinner table. She had to get Dad a glass of water after he slurped some up on a homemade tortilla.

“That’s hotter than the surface of the sun,” he said when he could speak. “What color is it?”

“Green.”

“Ah.” He took another gulp out of his glass. “We could use that to clean the drains too.”

“She doesn’t have to fix dinner.”

“She’s a good cook.”

“We’re good cooks,” Lucy said.

“This is kind of nice though, isn’t it? Just sitting down and relaxing over a meal?”

He looked so much like he wanted the answer to be yes that Lucy said, “Sure.”

Dad dabbed at his eyes with a napkin. “I hear you actually got your homework done.”

“Dad, she practically chained me to the table. Me and her granddaughter.”

Dad chuckled. “You weren’t so crazy about Mona?”

“Mora. She thinks we’re boring because we don’t have a computer and satellite.”

“You don’t have to be best friends with her.”

“That’s good because it isn’t gonna happen.” Lucy suddenly felt squirmy. “Can I be excused?”

“You’re done already? I haven’t even started. Keep me company.” Dad put his hand right on the plate of sopapillas that were oozing butter and sugar, as if he saw them with his nose. “Have some of these — it smells like she stole them from heaven.”

“I don’t want dessert.”

Dad’s eyebrows lifted. “Okay, who are you, and what have you done with my daughter?”

“Da-ad.”

“Lu-uce.”

Lucy picked up her plate. “I’m gonna clean up.”

He laughed out loud. “Now I know you’re avoiding me. Sit down. Have a — what are they — sopapillas?”

Lucy plunked back into the chair, but she forced herself not to reach for one of the white puffs she’d watched Inez create at the same time she was drilling Mora on her vocabulary words and checking Lucy’s fractions.

“Talk to me,” Dad said. “Did you like Inez?”

Lucy saw her chance and formed her words carefully. “She told a lie.”

Dad’s eyebrows went up even farther. “And that was?”

“Are you ready for this?” Lucy got up on one knee. “She said that you said that I had to sit down and have a snack before I did anything else. No, she said you ‘ordered’ it.”

She sank onto her foot and waited for him to call for Inez to be fired immediately. He tapped his plate with his fork.

“I need coordinates,” he said.

Lucy leaned across the table. “Meat at twelve o’clock. Beans at three. That evil salsa at six o’clock. Salad at nine. Don’t you even care that she lied to me?”

Dad tasted the pork before he answered. “That was the truth. I wanted you to have something more nutritious than Pasco’s.”

“We don’t care about nutritious!”

“We do now.”

Lucy poked her finger into a sopapilla.

“I take it you didn’t sick Mudge on her.”

Marmalade chose that moment to hop onto Dad’s lap and twitch his whiskers at his plate. Lucy felt a small twinge of guilt. But only a small one.

“Keep your paws off, pal,” Dad said.

Lucy pulled her hand out of the dessert. “I was good. But, Dad, I’m almost always good. Which is why I don’t need a nanny. Pasco watches out for me — and Mr. Benitez isn’t going to let me get away with anything, and — ”

“We’ve already been there.” Dad closed his eyes and eased a forkful of beans into his mouth. “That’s heaven too.”

“Whatever.”

His face grew still, and all trace of angels faded from it. “You promised to give this a fair try for two months.”

“One month and twenty-nine days,” Lucy said.

The only way she was going to get through it, she told Lollipop later as they snuggled with the big stuffed soccer ball on her bed, was if J.J. really did have a place for them to play without Gabe and the Gigglers. And that bossy Mr. Auggy.

“Okay,” she said to the purring face that was nose-to-nose with hers. “So he said I rocked. But he makes us play with people who don’t even care about soccer.”

She relocated Lolli into the pillows and knelt to look out the window. The lights in J.J.’s house tried to shine through the bedsheets Mrs. Cluck draped across the windows for curtains. J.J.’s, on the second floor, was dingy white, perfect for hand signals if he pointed his flashlight at it.

She watched, chin resting on the tile windowsill, but no message appeared from J.J.’s fingers. And Januarie didn’t show up with a pizza delivery. Lucy felt very much all by herself. Dad could probably use some company listening to NPR —

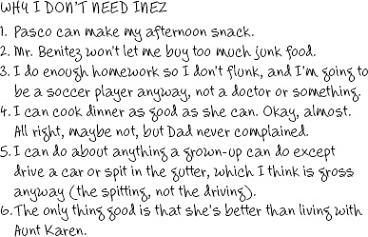

But Lucy pulled the Book of Lists from her underwear drawer and hugged it to her until the next list idea came to her.

Number Six made it easier to go to sleep.

J.J. just grunted the next morning when Lucy met him and Januarie outside the gate. He wasn’t on his bike, so Lucy walked hers. Januarie chattered away, but Lucy studied the side of J.J.’s face. It was stiff as the frost inside Dad and Lucy’s freezer — the one Aunt Karen always said they needed to replace with the kind that defrosted itself.

Finally, when Januarie ran off to join the third-graders, Lucy said to J.J., “Well?”

“What?”

“New place to play today?”

“No. Saturday.”

“Why?”

“Januarie and her big mouth.”

“Grounded?”

Grunt.

The warning bell rang, and Lucy hurried into the sixth-grade wing to put her soccer ball into her cubby. Late as it was, the hallway was empty, except for one person. Lucy groaned inside when Dusty turned from her perfect lineup of color-coded notebooks.

“Hi,” she said.

Lucy shoved a nest of papers into the back of her cubby and pushed her soccer ball carefully in front of it. What was Dusty up to now?

“Hi,” Lucy said into her cubby hole.

“So — who was that lady that was with you at church that one day?”

“My aunt. You want her?”

“Huh?” Dusty said.

Lucy set her backpack on the floor so she could pull out the books she needed, and Dusty came to stand above her.

“Where did you learn to play soccer?” she said. “You play pretty good, for a white girl.”

Lucy stood up, backpack in hand. “For a white girl? Haven’t you ever heard of Mia Hamm — Julie Foudy — Michelle Akers?”

Dusty wrinkled her nose. “What smells?”

“Not me.” Lucy whirled to head the other way and nearly ran into Mrs. Nunez, the principal. She was so close that Lucy could see the line she’d drawn around her lips to fill her orange lipstick in. Lucy turned, jammed her lunch into her cubby, and tried to get to the door without looking at her again.

“You need to work on that cubby, Lucy,” Mrs. Nunez said in that voice that always sounded like she was talking to one of the kindergartners.

“The bell’s about to ring,” Lucy told her, as she hurried down the hall.

“You could take a few lessons from Dusty.”

Lucy pushed the door open and imagined Dusty looking like she’d just scored a goal. Yeah, they definitely had to get away from her. Saturday couldn’t come fast enough.

There were two more days of recess soccer to get through — with the usual giggling and tripping and whistle-blowing that drove Lucy nuts. And two afternoons doing homework over beany burritos while Mora told Lucy she was practically a cavegirl because she somehow survived without the Internet and a camera phone. And Mr. Auggy’s assignment, which involved putting all her pictures on a piece of poster board in a big puzzle called a collage, which didn’t have anything to do with English, as far as Lucy could tell. But as long as it kept her from having to make a fool of herself trying to write a paragraph, she was willing to cut and arrange and glue all period.

J.J. still didn’t earn a ding-ding-ding, but Lucy was ready to give him one herself when Saturday morning finally came. He was waiting outside the gate when she finished her litter box emptying chore — the one thing Inez refused to do — blue eyes glowing warm in spite of the bite of the New-Mexico-winter air.

“Hurry,” he said. “Before she gets up.”

Januarie-less, they biked down Granada Street, past the church and Mr. Benitez’s store and his house with the now-naked rose bushes napping and waiting for spring. Pasco’s wasn’t even open yet, and neither was Claudia’s House of Flowers with its Valentine boxes in the windows or Gloria’s Casa Bonita with the shades drawn on the hair dryers and rows of nail polish bottles which Lucy didn’t want to see anyway. She liked the town early in the morning, before it woke up and Mr. Benitez swept his sidewalk and glared at Pasco, who didn’t sweep his, and Claudia complained that the smells of Gloria’s perms were wilting her orchids, and Mr. Esparza just stood in his doorway looking disappointed because no one ever came to see the dusty pottery.