M. K. Hume [King Arthur Trilogy 04] The Last Dragon (32 page)

Read M. K. Hume [King Arthur Trilogy 04] The Last Dragon Online

Authors: M. K. Hume

‘Taliesin will cause a world of trouble for Arthur and Bedwyr by playing these power games.’ Lorcan scowled fiercely. ‘He wants to replicate Myrddion’s influence over the Dragon Throne by using our boy as his pawn in the game of kings. Arthur shouldn’t be treated as an extension of his father. He’s his own man and should be treated with the respect he deserves.’

‘Not likely, given Taliesin’s nature,’ Germanus muttered. ‘He’s a poet rather than a warrior, so I doubt he recognises Arthur as a person, only as a character in a song he’s writing. He loved Artor, but such devotion has left no room for anyone else. Making the son of the Dragon into another High King isn’t treason in Taliesin’s eyes. It’s just a natural progression.’ The arms master heaved a deep, regretful sigh. ‘We must watch him all the time, Lorcan, or Arthur might be sacrificed because Taliesin has reached too high. But for the moment we’ll say nothing, and allow the boy to enjoy building his dyke.’

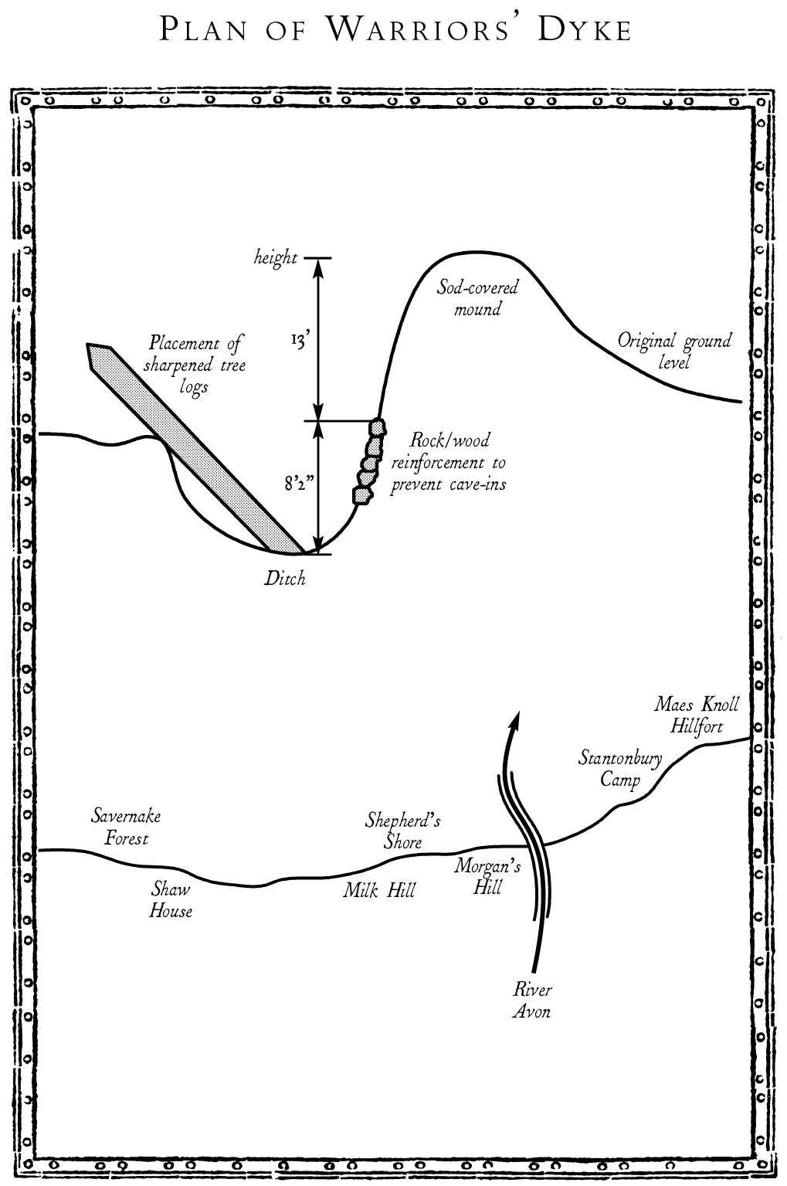

A week later, construction began with much enthusiasm and the cheerful throwing of a great deal of mud. The ancient stone fortress sited on one of the hills became the starting point, and peasants, warriors and aristocrats were soon at work with shovels and primitive digging implements in a laughing, democratic bunch. In a relatively short period of time, a ditch eight feet deep and fifteen to twenty feet wide was excavated for a distance of some twenty feet. The soil was thrown onto the south-western side and formed into a mound rising some ten feet above ground level to ensure that the defenders would always look down on the attackers as they approached from the north and east. Mantraps would be installed at varying intervals to impede any attacking force. Below ground level, Taliesin’s skilled workers shored up the earth with fieldstone collected from the site while sod was cut to cover the raw, muddy surface and consolidate the mound.

When Arthur stepped away from the ditch to evaluate Taliesin’s initial planning, he could see the purpose of the earthworks immediately. From the bottom of the ditch, any attacker would be faced by a stone and sod mound rising nearly twenty feet above him. Once in the ditch, the enemy could be easily attacked from above, while the sloping banks provided protection for the defenders.

‘See, Arthur?’ Germanus explained, his dirt-stained hands indicating the deep ditch and the mound towering above it. ‘If we set some dressed and spiked tree branches into the walls of the dyke, we could hold an army here and stop it getting through to the softer lands to the west. Look where the dyke will be built.’

Germanus pointed into the distance and Arthur saw what Taliesin had realised when he first came to the narrow valley that led into the west. Pilgrims had travelled along this route for hundreds of years, passing on to Glastonbury and Joseph of Arimathea’s church via the easiest gaps in the mountain chain. ‘See how small hills are aligned across the valley? We will build the dyke from hill to hill, across the river and the plain to the dense forest that protects the south. In such a way, we can control any enemy who tries to pass.’

‘I understand. Taliesin is a clever man to pick this spot, for many great towns will be protected by this ditch. I see now that I referred to it as the Warriors’ Dyke in a fit of stupidity. It should be named for its builders, rather than warriors, for only a small number of those will be needed in its defence once it is completed. The rest can be redeployed in other places.’

As the work advanced, Arthur became increasingly important. The labour was back-breaking, so the boys would have lost interest quickly if Arthur hadn’t explained the dyke’s strategic importance. ‘We are working here to save our tribes from attack. Ask the Atrebate warriors what it feels like to have Saxons living so close that you can almost spit on them. And they have no ditch to protect them.’ He smiled at his awestruck audience. ‘The work will become a little harder once we reach the flat lands, for the earth is soaked in water. According to the legends, Glastonbury was once an island in a great inland sea, and some farmers have found shells in the plains round here. If we are lucky, we might even find some ourselves.’

What lad could resist such a challenge? Try as they might, the young aristocrats found no shells, but in the vicinity of the fortress they discovered a number of bones, well gnawed by human teeth, and the remains of a number of broken, yellow-coloured clay pots. Arthur stared up at the ruins on the hill and imagined men throwing away the bones during the long watches of the night as they prayed to their gods to protect them from some long-feared enemies. Could those old defenders have been Picts, the blue-tattooed people who had been displaced so casually by the Celtic invasion? If so, the souls of those long-dead guards must have been rejoicing now in the shadows where they gathered to wait for their enemies.

The lads were fascinated by the tales that Arthur conjured out of the rubbish that was revealed by their toil. One week passed and twelve feet of wall and ditch was completed, leaving Taliesin to conclude that the dyke could take as long as five years to finish. If his figures were correct, it could be a wasteful and pointless exercise.

The next day dawned with grey skies and the threat of rain, but as Arthur told his young friends, the digging would always be hard work whether it was carried out in rain or sunshine. He examined a row of blisters on his palms and vowed that they could manage the next ten feet in no time at all. ‘I have better things to do than work in the rain and the mud forever,’ he explained.

Everyone but Mareddyd agreed with his assessment, but the bully had made himself so unpopular that nobody in the encampment cared what he said. He was totally ignored, and this was the worst punishment that could be laid on him. Isolated, the Dobunni heir smarted with indignation that a Cornovii nobody should be looked up to while he was not. For his part, Arthur took no part in the judgement of Mareddyd’s peers, who roundly despised the prince for bullying the smaller boys and lording his superior birth and wealth over everyone around him.

The further the work progressed down the slope of the hill, the more the workers were hindered by mud. Arthur turned their hard labour into a game so that the young men struggled on, coated in heavy, clinging sludge which at least repelled the stinging insects that bred in these marshy lowlands. By comparing blisters around the campfire at nights and through Arthur’s constant good humour, the aristocratic youngsters discovered they were enjoying themselves.

‘Remember, friends,’ Arthur explained one evening as he wrapped his abused palms with clean bandaging, ‘the warriors and the peasants take their attitude to the dyke from us. If we are lazy, or if we complain about the difficulty of the work for no reason, they will follow our lead and also complain. This task is important, and we should be proud to play our part in it. I’m committed to what we’re building, even if I know that peasants can do the digging faster and better than I do. When I’m an old man, I will look back at the Warriors’ Dyke and say that I helped to build it and keep my people safe from harm. What are a few blisters compared with a goal like that?’

The nights passed in spirals of wheeling stars that seemed so close that Arthur could reach out his spread fingers and capture their chilly beauty in his hands. Although his muscles ached from the endless toil of digging, no mental screams of warning came to disturb his sleep and no threats of danger whispered from the back of his skull. Only the night breeze soughed through the fields of long grasses and sang melodies of ancient beauty in the leafy branches of young trees. Time stood still during those long, dreamy nights as the breezes brought the scents of spring and growing things to Arthur’s senses, and he prayed that this stage of his life would never end. The peace of ordinary men and women came hand in hand with the cleansing honesty of toil that soothed the mind with a promise of long, warm days and sweet, refreshing nights.

So summer came to the flatlands leading to the heart of the west. The ditch was now almost three miles long and the peasants were filling its long, straight channel with sharpened stakes that pointed menacingly towards the east. Ahead lay the river, Taliesin’s greatest challenge so far, although the waters were narrow here where the stream flowed down from high in the hills where it began its journey. Arthur waited for the day when Taliesin would explain how the ditch would intertwine with the singing, living water at the point where Taliesin had chosen to make his crossing.

Breathless, the world also waited in a hush of summer nights.

CHAPTER X

A DANGEROUS ENEMY

The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked.

Jeremiah 17:9

With a new stoicism, Arthur stared down at the dancing, gurgling waters of the river that could bring a year’s labour to nothing. Not particularly wide nor overly deep, it still posed problems for the workers because marshland on both banks brought stinging insects and green clouds of gnats to feast on any exposed flesh.

‘What’s to stop the Saxons from loading rafts with their wagons and possessions and using the river to slip through into the west once we’ve gone? That’s what I’d do if I were in their boots,’ Arthur exclaimed to Taliesin when he saw the marshy banks.

Taliesin observed Arthur’s serious expression with approval. He had been concerned by the younger man’s enjoyment of company and his sense of humour, traits that Taliesin’s earnest nature rejected as unnecessary. Arthur seemed to like everyone, and such fair, unprejudiced tolerance was not an ideal characteristic for a man who was born to rule.

‘As always, Arthur, your questions are pertinent, but I would never waste months of my time building a dyke that could be easily bypassed. I have already solved the problem of how the ditch should cross the river.’ Taliesin raised his hand and used his forefinger to emphasise the points he wanted to make by stabbing the empty air. ‘First, we need to be aware of the Saxons’ intentions in plenty of time to take action against them if they try to load their wagons onto rafts. A small troop of warriors will be based in this area and regular patrols will be carried out to monitor their movements. But in any case, the land is marshy upstream from the ditch and it would be almost impossible to load and launch any rafts from there.’

Arthur nodded. So far, Taliesin’s reasoning seemed sound.

‘Second, I plan to build a further obstacle to hold back the Saxons once our ditch has been completed. The small troop of Celts who will be left to guard this section of the wall will easily be able to handle the set of chains I intend to place across the river. The chains will be invisible under the water until such time as they are raised into position to block the channel.’

‘Chains?’

‘Yes, Arthur, chains. My father saw the great ropes of iron that seal off the harbour of the Golden Horn at Constantinople with his own eyes. As a boy, I tried to imagine the vast blue harbour shining in the sunlight and the network of chains that lay under the water. In times of danger, slaves would use huge pulleys to raise the chains up to bar the way of warships and prevent them from entering. Can you imagine the scale of it all? They used hundreds of yards of chain mesh, which is incredible when compared with our paltry thirty feet. Our small net is tiny by comparison, but it will be quite sufficient to achieve our purpose.’

Taliesin’s eyes glowed with enthusiasm and his chill features were flushed with colour for the first time in Arthur’s memory. Suddenly, Arthur wondered what he would have been like had he not been blighted by the last bitter days of Artor when he was little more than a boy. He was beginning to suspect that the harpist was determined to see the High King reborn and raised to his natural prominence in British life, whether the successor wanted such power or not. And he had a shrewd idea whom Taliesin wanted that successor to be.

Taliesin strode effortlessly along the marshy banks of the stream, his long black hair whipping in the strong breeze. ‘Imagine, Arthur. The structure at Constantinople comprised a vast net of iron chains as thick as a man’s upper arm that could block the harbour entrance. Father’s account of it set me to thinking of what we could do here at our little river. A simple system of chains could immobilise any rafts or troops of horsemen that attempted to come downstream and block the easiest route into the west country. We would only need two men with a pulley system to raise and lower the chains. I’ve already drawn up the plans, and my brother Rhys has come to oversee the construction of the system.’

Arthur stared at the scrap of vellum on which the harper had sketched out the mechanical details of the chain gate. ‘I’m awed by how easily you calculate the answers to difficult problems. By the grace of the gods, you have an enquiring mind that leaves other men stumbling through the darkness of ignorance.’

‘The gods? Your mother is Christian, so I assumed that you shared her belief,’ Taliesin said softly, with a blank expression that showed only polite interest. Under his bland demeanour, however, he was pleased that Arthur had no religious affiliations, for such neutrality reduced the chances of manipulative priests gaining ascendancy over his mind.