Macrolife (9 page)

Authors: George; Zebrowski

“I like her,” Sam said, “and I think Janet likes her.”

“Governor Alard will take us in on Asterome,” Orton said. “Besides, Bulero has offices and facilities at L-5. You can be sure that the Bulero people on the colony have told Alard about the danger. If I know him, he's stripping the asteroid of what little bulerite he has right now.”

“We'll go there for now,” Sam said. “It's a free state, where we have some rights, as you say.”

Â

Sam got up in the darkness and put on his robe. When he was sure that he had not disturbed Janet, he went out into the main room. Margot was asleep on the air mattress in front of the fireplace. Orton was sprawled across two mattresses in the alcove next to the basement door. Moving quietly, Sam stepped outside.

The village was a dark abyss. A night wind swept from the mountain behind him. The snow on the peaks across the valley was bright in the starlight. Suddenly he knew that the security of the valley was an illusion; the immensity of these mountains was an illusion. Only the stars would endure, shining even when the earth was gone. The stay in the valley was a doomwatch, nothing more.

He went inside quietly, lay down next to Janet, and tried to sleep as he listened to the wind.

But the earth moved under him, gently at first, then shaking the house, conspiring with the wind to drive them off the earth.

They dressed quickly, and Sam led the way to the helicopter.

The blades started nervously, but finally Janet was able to coax the overburdened craft up from the shaking block. With luck, Sam thought, they would reach the Machala airstrip before morning, long before the fuel ran out. From there it was only an hour to the equatorial earthport at Quito.

He thought about Richard.

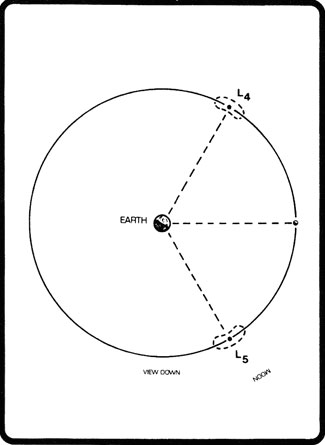

Asterome was a settlement in space, circling the earth at Libration Point 5, a quarter of a million miles behind the moon's position, equidistant from earth and moon. The tourist screen at the end of the shuttle aisle showed a diagram:

The screen switched to an occasional view of earth, stars, or moon, always returning to the diagram as if to a test pattern.

Sam turned and looked at Janet; she ignored him, staring ahead, hands clasped in her lap. She had failed to reach Richard from Quito, and it had been difficult to get her on the shuttle. Margot had taken her side, but after some discussion both women had been convinced to board the moonbus. Sam was not happy about leaving, either, but Orton had insisted that Richard would follow with Mike Basil. All four of them now understood that there was very little they could have done by staying behind, whether Richard followed or not. For the moment, Sam told himself, there was no reason to think that Richard was in danger.

He turned and glanced at Orton and Margot in the seat behind his and Janet's. They were asleep, floating gently against their seat belts.

There were no familiar faces among the other ninety-six passengers; it was obvious that they were well-to-do skilled people on their way to Asterome and the moon, probably to replace people who had left, to continue their professional experience and studies, or to fill new positions.

The twenty-four-hour passage had grown oppressive. As the shuttle maneuvered for the final approach, Sam tried to relieve his worries by recalling something of the history of Asterome. He had been relatively ignorant of the community, he admitted, until Richard had gone to study on the moon and had written letters home about the place. Even now, Asterome was difficult to imagine. Nothing, Richard had written, can replace the experience.

I'm more used to ideas than to experience

, Sam thought.

Even experience is a concept for me

. Emotionally he was not convinced that he was out in space. The viewscreen did not seem real; after all, stars, the moon, and space were not like streams and trees, or stones that one could touch. He remembered his grandfather's view of space travel and the notion of space habitats: wallsâ¦glass and metal, cramped cabins, a starry, desolate darkness outsideâ¦no life for a human beingâ¦.

Asterome was an arcology, much like the tier cities of earth-moon, a societal container housing a new branch of humankind. Once it had been a minor planet, a chunk of nickel-iron and rock ten miles long and five wide, roughly ovoid in shape, moving in an orbit that would have brought it into collision with earth five years after its discovery. In the late 1980s, the Japanese had sent out an engineering team to land on it, using a modified atomic version of a Type III American space shuttle. The group had brought supplies to set up housekeeping, as well as a nuclear rocket engine, industrial atomic explosives, and sunsails. After laying a solar-powered mass driver track along the length of the asteroid, and attaching the atomic engine for attitude correction, they had diverted the asteroid into the relatively stable L-5 position.

Sam imagined the moment when the mass driver had begun to move the asteroid by accelerating bits of rock off the surface opposite to the direction of travel, using the asteroid's own material and electrical power from the sun to change its orbit slowly. That must have been a moment without equal in the lives of the engineers, who had spent years in space to save earth from a great catastrophe.

The danger of collision had played into the hands of the International Asteroid Mining Lobby, which also ran the two equatorial earth-ports on a commercial basis. The lobby had argued that the energy expenditure to avert world catastrophe would show a good return on investment as Asterome grew to be self-sufficient; it would be silly to bring the giant rock into L-5 and do nothing with it. No one had doubted that an ocean strike by the asteroid would have permanently altered the earth's climate, plunging humanity into an ice age. Once the investment snowball had started, nothing could stop it; but it had taken a near disaster to start the development of the greater solar system.

It always takes a crisis to wake us up

, Sam thought.

The mining of the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter began even as the inside of Asterome was being hollowed out. Both ends were opened with nuclear charges, permitting the mining of the rich nickel and iron ore. When the interior space had been cleared, the ends were closed by installing recycling plants and multiple docking locks. The pumping in of a pressurized atmosphere and the arrival of colonist workers had signaled the birth of the first genuine macrolife settlement, capable of self-reproduction and mobility. The population had grown to a hundred thousand by the turn of the century, but the three hundred square miles of interior real estate could easily support a million.

Asterome was the shielded residential area of a growing industrial and scientific complex at L-5. Six large manufacturing structures used the space environment's cheap solar energy and unlimited heat and waste sink. Metals mined on the moon and in the asteroid belt were refined and cast with the high precision made possible by zero-g facilities, the use of controlled acceleration and gravity gradients, the high-quality vacuum, and other conditions available on earth only at high cost, if at all. The list of industrial processes continued to grow, even after a quarter of a century; many earthbound industries no longer bothered to make basic products; it was cheaper to import from free spaceâ¦.

Sam closed his eyes. Impersonal concerns had always been a comfort to him during bad times. Janet might be right about Richard, though she would not say it.

What could have happened

? Sam wondered. There were many things that might have delayed him; death was too extreme an explanation; Janet was almost certainly wrongâ¦.

Besides being a way station, Asterome provided space-rescue capability that could reach to any part of sunspace. The settlement's maintenance crews regularly serviced the solar energy collectors in near-earth orbit. The UN Space Fleet's dockyards were on the moon, where many of the ships were in mothballs, but the hired specialists from Asterome kept the vessels operational.

Richard's letters from Plato University contained a wealth of detail about life away from earth, more than Sam had cared to know at the time; but now something of Janet's foreboding took hold of him, and he was surprised at how much he remembered. The letters revealed, he realized, Richard's growing commitment to a new kind of life.

Asterome's best efforts went into basic research, following Daniel Bell's well-known description of a postindustrial society as one in which the organization of theoretical knowledge is central to innovation, a society in which intellectual institutions are the heart of the social structure. This was also true, to a degree, of societies on earth, but Asterome had the potential of becoming genuinely open-ended and self-shaping, creatively incomplete on the model of science and art, without having to live with the historical brake of economic insufficiency.

Â

In physics, gravity research, sun studies, the various astronomies and cosmologies, Asterome continued at a competitive pace with earth-moon, excelling in applied physics, especially in the improvement of solar and fusion power systems; in basic research, Asterome's forays into aspects of gravity wave generation led the field. In biology and medicine, Asterome dominated both research and applications, producing thousands of export drugs in special conditions, as well as providing safe areas for the more dangerous forms of biological research which had been banned from earth's biosphere by the various safety boards.

Sam thought of Laputa, Swift's fictional island in the sky, where all kinds of seemingly useless scientific research was carried out in the name of knowledge. Swift would have considered most of Asterome's activities inexplicable, unless he had radically altered his outlook. Richard had exhibited such a change in his letters from the moon, and Sam found himself approving the change. Richard had prepared him for Orton's visions; but they were not Orton's property; a large group of people shared them. Sam wondered how he would have tolerated these views in a colleague, rather than in a nephew and a friend.

The colonies on Mars and on the moons of Jupiter and Saturn could not have been founded without Asterome's support. Asterome had helped earth-moon corporations invest in exploration and development. It had built the Bulero Orbital Factory for the manufacture of bulerium, in addition to a half-dozen other Bulero space going facilities. Ganymede City could not have been built in Jupiter's radiation zone without the shielding for the construction crews provided by Asterome. The asteroid's ties were strong with every human settlement in sunspace, Sam noted; it had even helped with the first efforts at exploration beyond sunspace. Yet Asterome managed to remain independent, despite its ties, despite successive efforts by earth-moon multinationals to buy up control of its stock.

Asterome's governors had been mostly Japanese, except for a few Chinese in the late 1990s. Their stewardship of a thriving crossroads community had revived Asia's self-respect and sense of legitimacy in world affairs, especially after the Russian civil war had left the USSR as two associated republics. The six-month war had destroyed a quarter of China's industrial capacity; Moscow had termed it a preventive strike, made to discourage China from taking advantage of the civil emergency. The close call with full-scale nuclear war had finally brought a UN Nuclear Arms Control Treaty, beginning a process that might one day have resulted in a total ban.

Sam thought again of the initial act of daring that had resulted in the building of Asterome, in the gathering of skills and investment for the industrial development of the asteroid belt, in the opening of the solar system's vast wealth for human use. A huddling humanity had needed to grow beyond the limits set by a century which had been learning to be a miser in a universe of plentyâ¦.

The earth eclipsed the sun on the screen. The view changed and Asterome's docking chutes gaped at him as the shuttle made its approach, slowly correcting its forward drift.

“We're almost there,” he said, floating gently against his seat belt.

The screen went blank as the craft docked; through the port at Janet's right, Sam caught a glimpse of a metal plain and a close, ragged horizon of slag and rock. His stomach felt queasy as his mind produced an illusion: The shuttle had landed nose first and “down” was directly ahead; at any moment he would fall forward and shatter the screen.

Janet grasped his hand. The perspective disappeared as the vessel was drawn inside, covering the port.

A voice spoke from the screen, warning passengers to be careful when they released their seat belts.

“We're still at zero gravity,” Sam said, “because the docks are along Asterome's long rotational axis. Gravity will return as we move off that axis.”

“No kidding,” Janet said as she floated over him into the aisle. She was making an effort, he knew, to appear cheerful.

“I was trying to explain,” he said, “but maybe I should have started with the difference between centrifugal and gravitational forces.”

Orton and Margot were gliding toward the nose exit. Janet pushed after them. Sam waited until the other passengers had drifted out, then followed; he floated to the exit, passed through a long curving tunnel, and emerged into a small green room, where Janet, Margot, and Orton were waiting. At once his feet drifted down to touch the floor, and his stomach noted the change.

The walls seemed recently painted. There was a rack with a dozen spacesuits and a small screen next to a portal leading into another long tunnel. Sam walked over carefully and looked into the dimly lit passageway.

“The place is honeycombed with rooms like this. I guess it's a reception area,” Margot said.

“Is someone meeting us?” Janet asked.

Sam saw a man's head in the passageway; shoulders became visible, then a torso and feet. The figure was obviously coming around a curve. In a moment the man stepped into the room.

“I'm Governor Amadis Alard,” he said, smiling. He was dressed in green shorts and sneakers, his black chest bare. His hair was closely cropped, resembling a black skullcap; touches of gray were visible.

“Samuel Bulero?” he asked, squinting at him. “Orton, we meet in the flesh at last. And Janet Bulero.”

“This is Margot Toren,” Janet said.

“How do you do. My helpers will show you to your housing. I'm very busy, as you may guess, so you will excuse me if I leave suddenly. This is the first time in decades that the Bulero family has asked to use its privileges on Asterome. You are welcome.” He spoke in a rich bass voice. Sam saw the uneasiness in Janet's face; Margot was not looking directly at the governor. “Where is Richard Bulero?” Alard asked.

“He'll arrive later,” Orton replied.

“We will go the way I came,” Alard said. “This spiral will take us farther away from the axis. You will note a gradual increase in centrifugal, or pseudo-gravitational, pull. But let me show you a view first.” He stepped over to the screen and turned it on.