Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies (22 page)

Read Mad Enchantment: Claude Monet and the Painting of the Water Lilies Online

Authors: Ross King

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Architects, #History, #General, #Modern (Late 19th Century to 1945), #Photographers, #Art, #Artists

Another problem was that, after more than eighteen months of war, France was facing certain privations. There was a tobacco shortage, with more than a million fewer cigarettes and cigars to be had compared

with prewar years.

29

Monet therefore expressed his gratitude in April to Charlotte Lysès for the gift of cigarettes. “They saved my life at the very moment I’d run out,” he told her.

30

Monet without a regular supply of cigarettes did not bear contemplation. He always lit up as he started painting but, preoccupied with his task, often tossed the cigarette away only half-smoked, leaving family members to gather up these butts and put them in a container through whose contents Monet, desperate for a puff, would later rummage “like a beggar.”

31

Besides tobacco, some foods were also more difficult to come by, and all cost considerably more. By the spring of 1916, cheese was 20 percent more expensive than its prewar price, butter 24 percent more, while beef had risen by 36 percent and sugar by an eyewatering 71 percent, forcing the government to set a maximum price in May (soon raised in October).

32

For the past year the French papers had been exulting in rumors that the Germans were reduced to eating bread made from straw, but in May the French government introduced “national bread” consisting of a third part wheat flour mixed with rice and rye, a coarse, crusty mixture that most people found inedible.

A newspaper declared that, since the needs of the army came first, it was “the duty of the civilian population to decrease consumption.”

33

Monet was therefore reduced to eating what he called “a modest wartime lunch.”

34

He offered Charlotte a harrowing view of domestic life with a tobacco-starved artist fretting because the weather was keeping him from his easel and the war from the pleasures of his table. He experienced, he told her, “moments of complete discouragement, causing great damage to those around me, like poor and devoted Blanche, who puts up with my bad moods.”

35

In July, Mirbeau arrived in Giverny for a visit. The deteriorating condition of his old friend was a cause of great concern to Monet. A visit in the spring—when Mirbeau had moved back to his house in Cheverchemont—was canceled because of the writer’s poor health. His appearance in Giverny two months later did nothing to inspire confidence. “What a dreadful state he is in, our poor friend,” Monet wrote sorrowfully to Geffroy at the end of July.

36

Indeed, the problems

were no longer merely physical, since by 1916 Mirbeau was reduced to a state of semiconsciousness for months at a time, often unable to recognize friends.

37

Monet may have received from the decrepit and disabled figure of his friend, eight years younger than himself, a haunting vision of his own looming future, a horrifying glimpse of what his life would be like if he, too, ever became incapable of work. Another friend was likewise struck down in similar fashion: Rodin suffered two strokes in quick succession—the second, on July 10, resulting in a fall down the stairs at his home in Meudon, outside Paris. He, like Mirbeau, was suddenly left unable to work, although he remained “quite happy—full of serenity and sweetness,” according to his friend and biographer Judith Cladel. Like Mirbeau, he suffered serious cognitive deficits: “He thinks that he’s in Belgium,” reported Cladel.

38

Another visitor that summer was Clemenceau, who came to Giver ny before departing for a rest at Vichy. Yet at least Clemenceau, despite his diabetes and overwork, offered an inspiring picture of physical and mental vigor. He had been continuing his war on all fronts, journalistic and political. In February he had chaired a meeting of the Franco-British Committee, of which he was president, thrilling and moving friends and enemies alike with his resounding rhetoric. “Clemenceau took the floor,” reported a newspaper, “and delivered one of the best speeches of his career—and we know Clemenceau has always been a good speaker.” He condemned the Germans and their “prodigious convulsions of barbarism” and spoke of French sacrifices: “We give our children, we give everything we own—everything, everything—and the wonderful cause of independence and the dignity of man serves as its own reward, and despite the most painful sacrifices we never complain that it has been too much.”

39

A little more than a week later, at the beginning of March, one of Clemenceau’s articles on the Battle of Verdun infringed censorship regulations, and once more his newspaper was suspended, this time for a week; a second newspaper,

L’Oeuvre

, was suspended for fifteen days for reprinting part of the offending article. Clemenceau was becoming

an increasingly controversial and divisive figure. Though loved by the

poilus

, whose cause he vigorously championed, he received ten death threats per day, many from those on the religious right. The editor of

L’Action Française

, Charles Maurras, who regarded him as damaging to national morale, denounced him as a “disastrous mountebank” and as “the anarchist Clemenceau.”

40

The charge of anarchism was baseless: Clemenceau’s address to the Franco-British Committee spoke of the rule of law as the basis of civilization, while even a newspaper generally not in accord with his political philosophy,

Le Figaro

, praised his “elevated patriotism.”

41

Equally absurd was the accusation of defeatism. To the Franco-British Committee he had used, for the first time, the phrase that would become his rallying cry:

“La guerre jusqu’au bout”

(“War until the end”).

MONET HAD ONE

other visitor late that summer: his son Michel, who returned to Giverny on a six-day leave after “three terrible weeks at Verdun.”

42

The battle was beginning to define the horror and futility of the Grande Guerre. A newspaper pointed out in August that the Battle of Verdun had already lasted as long as the entirety of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870–71.

43

By the summer of 1916, however, the German offensive was failing amid catastrophic losses on both sides. General Falkenhayn had been partially successful in his stated ambition to bleed France white, since by September the French dead and wounded amounted to 315,000 men. But the German casualties were equally horrendous. Erich Ludendorff, in charge of his country’s war effort, toured the battleground in early September, around the time Michel Monet was granted leave. Even the hardened Prussian general was stunned by the bloody devastation. “Verdun was hell,” he said. “Verdun was a nightmare.”

44

And yet fewer than two hundred miles from the hell of Verdun was the paradise—as so many of Monet’s guests called it—of the garden at Giverny. The contrast with Verdun could only have been

surréel

, a word that would be coined a few months later by Guillaume Apollinaire. Leaving the devastated landscape of Verdun, Michel Monet passed

through Paris, with its perverse displays of normality. (Besides films, plays, and musical performances, football games were played that summer, and a bicycle race was contested on the roads between Paris and Houdan.) He then reached Giverny to find his father, the most famous interpreter of the beauties of the French countryside, sitting before his easel as in days of old, apparently as unperturbed by events as the lush foliage and bright waters he was re-creating on his canvases.

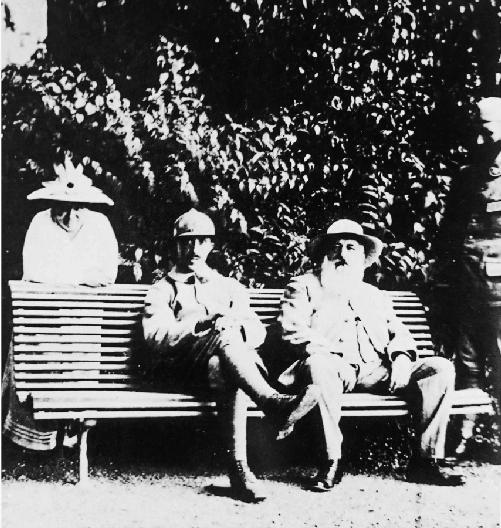

Monet with (

left to right

) Blanche, Michel Monet, and Jean-Pierre Hoschedé (

standing

) in 1916.

It is doubtful that Michel ever tried to explain the horrors of Ver dun to his father. Few soldiers of the Great War were able to speak of what they had seen: “We could no more make ourselves articulate,” wrote one of them, “than those who would not return.”

45

But the nightmarishness of the war was made clear in the hellish summer of 1916 to readers of

L’Oeuvre

, the newspaper that had been suspended in March for printing Clemenceau’s article on Verdun. In August the newspaper began serializing

Le Feu

, a war novel by Henri Barbusse, dedicated to “my comrades who fell beside me at Crouy and on Hill 119.” Barbusse hoped to puncture romantic notions of warfare with an astonishingly frank description of its true horrors. As one soldier in the novel, the ironically named Paradis, says to the narrator: “War is frightful and unnatural weariness, water up to the belly, mud and dung and infamous filth. It is befouled faces and tattered flesh, it is the corpses that are no longer like corpses even, floating on the ravenous earth. It is that, that endless monotony of misery, broken by poignant tragedies; it is that, and not the bayonet glittering like silver, nor the bugle’s chanticleer call to the sun!”

46

Amazingly,

L’Oeuvre

somehow escaped the censors, and later in 1916 the novel was published in book form (and swiftly translated into English as

Under Fire

). Monet may not have read Barbusse’s novel in either format, but the novel’s harrowing portrait of the war was the subject of discussion at the Goncourt luncheons. Monet was still as active as ever in these meetings of the “Goncourtistes,” as he called them, even advocating the postponement of one session until Mirbeau was well enough to attend: a gathering of Les Dix without Mirbeau was, Monet told Geffroy, “an impossible thing.”

47

In 1916, Les Dix decided that the only novels eligible for the prize would be those written by men who had served in the war. In December, the Prix Goncourt was awarded to Barbusse.

ON THE SAME

day that the Prix Goncourt was awarded, the Senate voted in favor of providing government funds to establish the “Musée Rodin” in the Hôtel Biron. That autumn the newspapers had been full

of news of “

la donation Rodin

,” with the Chamber of Deputies voting in favor of the bequest in September and the Senate then debating the issue throughout October and November. Acceptance of the donation—valued at 2.5 million francs and including Rodin’s house at Meudon—was a close-run thing, since many senators were reluctant to spend government funds on the museum during a time of war. As one of them retorted: “I want to know what the

poilus

in the trenches think of such a debate.” However, proponents of the scheme argued that Rodin was “the poet of marble” and the “great national artist.” One senator argued that the war must not prevent the French from fostering “the cult of beauty.”

48

At long last, on December 22, Rodin’s donation to the state was, as the law emphatically declared, “definitively accepted.”

49

One powerful senator, however, declined to speak in favor of the Rodin donation. Clemenceau did not hold the esteemed sculptor in high regard: “He was stupid, vain, and cared too much about money,” he once told his secretary.

50

That may have been so, but the discord between the two men had other roots. He and Rodin fell out over a bust the sculptor made of Clemenceau some years earlier at the request of the government of Argentina (to which Clemenceau had paid a visit in 1910). “He completely botched me,” Clemenceau complained, “this sculptor whose busts recall the finest Roman portraits, and who captures features of which the model is unaware. I have no vanity, but if I have to survive, I do not wish it to be in the aspect that Rodin created.”

51

He believed Rodin had made him look like a “Mongol general,” to which Rodin retorted: “Well you see, Clemenceau, he is Tamerlane, he is Genghis Khan.”

52

When Rodin refused to tweak the bust, Clemenceau denied him permission to exhibit it at the Salon of 1913. The two men never spoke again.

NOT FAR FROM

the Hôtel Biron, on the other side of the Invalides, another project was taking shape with even greater enthusiasm and support from the authorities. Like Monet, the painters Pierre Carrier-Belleuse and Auguste-François Gorguet found themselves in urgent need of a more commodious space. In November they took possession

of a temple-shaped exhibition hall that had been purpose-built—thanks to funds raised from sponsors and subscribers—for their massive panorama,

Le Panthéon de la Guerre

. The new building occupied land owned by the École Militaire that had been granted to the painters by General Joseph Gallieni, the military governor of Paris. They and their team of helpers moved all of their paintings and designs into the structure—not only the thousands of square feet of canvas but also the tons of metal armature that would be used to suspend the paintings.