Magnificent Delusions

Read Magnificent Delusions Online

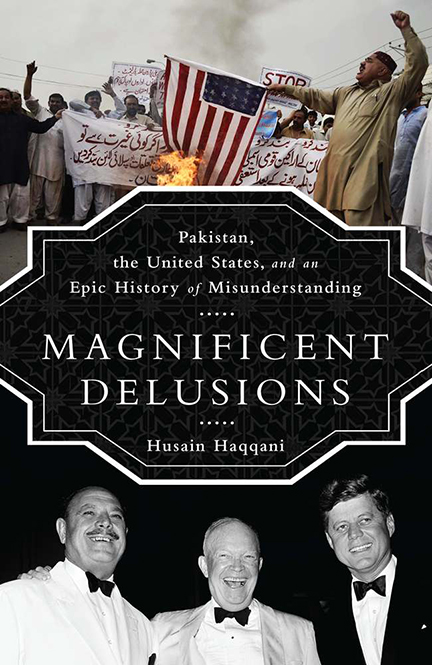

Authors: Husain Haqqani

MAGNIFICENT

DELUSIONS

MAGNIFICENT

DELUSIONS

Pakistan, the

United States,

and an

Epic History

of

Misunderstanding

.....

Husain Haqqani

P

UBLIC

A

FFAIRS

New York

Copyright © 2013 by Husain Haqqani

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs

â¢

, a Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Public Affairs, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail

[email protected]

.

Editorial production by

Marra

thon Production Services.

BOOK DESIGN BY JANE RAESE

Set in 12.5-point Bembo

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013948306

ISBN

978-1-61039-318-8 (e-book)

FIRST EDITION

2

Â

4

Â

6

Â

8

Â

10

Â

9

Â

7

Â

5

Â

3

Â

1

T

O MY LATE PARENTS

S

AEEDA AND

S

ALEEM

H

AQQANI,

AND MY WIFE

, F

ARAHNAZ

I

SPAHANI,

FOR THEIR LIFELONG LOVE, SUPPORT, AND ENCOURAGEMENT

Contents

Chapter Two: Aid, Arms, and Bases

Chapter Three: A Split and a Tilt

Chapter Four: Picking Up the Pieces

Chapter Five: A Most Superb and Patriotic Liar

Chapter Six: Denial and Double Game

Chapter Seven: Parallel Universes

A doubtful friend is worse than a certain enemy. Let a man be one thing or the other, and we then know how to meet him.

âAesop,

Aesop's Fables

MAGNIFICENT

DELUSIONS

O

ver the last two decades US-Pakistan relations have often been described as America's most difficult external relationship. Although the two countries have been nominal allies dating back to Pakistan's independence in 1947, their relationship has never been free of friction. Even in its heyday during the 1950s and 1960s, the US-Pakistan partnership was far from an alliance based on shared values and interests; instead, each of the two partners was always preoccupied with confronting different enemies and pinning different expectations to their association.

Pakistan's motive in pursuing an alliance with the United States is driven by its quest for security against its much larger neighbor, India. Pakistan has repeatedly turned to the United States as its most significant source of expensive weapons and economic aid. Although, in the hope of winning US support for Pakistan's regional aims, Pakistani leaders have assured US officials that they share the United States' global security concerns, Pakistan has been repeatedly disappointed because the United States does not share Pakistan's fears of Indian hegemony in South Asia.

For its part, the United States has also chased a mirage when it has assumed that, over time, its assistance to Pakistan would engender a sense of security among Pakistanis, thereby leading to a change in Pakistan's priorities and objectives. The United States initially poured money and arms into Pakistan in the hope of building a major fighting force that could assist in defending Asia against communism. Pakistan repeatedly failed to live up to its promises to provide troops for any of the wars the United States fought against communist

forces, instead using American weapons in its wars with India. Furthermore, US hopes of persuading Pakistan to give up or curtail its nuclear weapons program or to stop using Jihadi militants as proxies in regional conflicts have similarly proved futile.

Three American presidentsâDwight D. Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnsonâhave asked the question: What do we get from aiding Pakistan? FiveâJimmy Carter, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obamaâhave wondered aloud whether Pakistan's leaders can be trusted to keep their word. Meanwhile in Pakistan, successive governments have spent a lot of time trying to figure out how to maintain Pakistan's freedom of action while depending on US aid. But neither country has changed its core policies nor have they given up the hope that the other will change.

The US-Pakistan relationship has depended largely on cordial ties between leaders and officials who have often misunderstood each other's intentions and limitations. Whereas Pakistanis have often benefited from the American tendency to ignore history and focus only on immediate goals, Americans have often assumed that building up Pakistan's economic and military capacity provides them leverage even after periodically finding out the limits of US influence. And both sides have their own stereotypes about each other, traceable back to Pakistan's emergence as an independent country.

During that period, soon after emerging from British India's bloody partition in 1947, Pakistan's leaders confronted an uncertain future for their new country. When most of the world was indifferent to Pakistan as the potential homeland of South Asia's Muslims, India antagonized Pakistan without compromise or compassion. Because of this, soon after independence Pakistan's founding fathers, encouraged by some British geostrategists, decided that they would continue to maintain the large army they had inherited even though the new nation could not afford to pay for it from its own resources and did not immediately face a visible security threat. Given Pakistan's location at the crossroads of the Middle East and South Asia and its relative proximity to the Soviet Union, Pakistanis assumed that the United States would take an interest in financing and arming

the fledgling new state. Thus, the gap in expectations between American and Pakistani leaders that has bedeviled their relationship over the last sixty-five years should have been apparent right at the beginning, when Pakistan's founding father and its first governor-general, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, asked the United States for a $2 billion aid package in September 1947, but the United States gave Pakistan only $ 10 million in assistance that first year.

International relations thinkers like Hans J. Morgenthau and George Kennan did not see Pakistan's value to the United States as an ally. After all, Pakistan's primary concern, competing with India for regional influence, was not a strategic concern for the United States. But after Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected president in 1952, his secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, embraced the idea that Pakistan could be influenced into sharing US strategic concerns in exchange for weapons and aid.

Primarily because of geopolitical considerations, the United States has enlisted Pakistan as an ally on three occasions: during the Cold War (1954â1972), the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan (1979â1989), and the war against terrorism (2001âpresent). In each instance the US motive for seeking Pakistani alliance has been different from Pakistan's reasons for accepting it. For example, after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan the United States saw an opportunity to avenge the Vietnam War and bleed the Soviet Red army with the help of Mujahideen, militant Islamist radicals trained by Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and funded by United States' Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Pakistan, however, looked upon the military action in Afghanistan as a Jihad to be used as the launching pad for asymmetric warfare that would increase its clout against India.

Since my days as a student at Karachi University, I found the anti-American narrative that was prevalent all around me difficult to believe. I spent many hours at the American Center Library, reading books and articles that exposed me to different perspectives of historic events. Unlike my colleagues, I could see through the absurdity of conspiracy theories.

When student protestors burned down the US embassy in Islamabad in 1979, 1 was a student leader allied to Islamists on my campus.

A huge demonstration was organized at short notice, with university buses commandeered to transport protestors to the US consulate in Karachi. Several student speakers urged the mob to burn down the consulate, and the mob was ready to do so until I was called on to speak. My speech, citing the Quran and demanding that ascertainment of facts precede action, saved the US consulate (and its library) from meeting the same fate as the embassy in Islamabad.

Later, as a journalist, I covered the anti-Soviet Afghan war, observing firsthand the flow of US arms to the Mujahideen. My first foray into government was as adviser to Nawaz Sharif, who, in 1989, aspired to become prime minister of Pakistan. I accompanied Sharif on his introductory visit to the United States as opposition leader. Once Sharif became prime minister, I acted as his liaison with US media and diplomats before we parted ways quietly after differences of opinion.

In 1992 Pakistan's support for Jihadi groups nearly caused it to be designated a state sponsor of terrorism. I worked with Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, who, in 1993, succeeded Sharif's first government and worked to fend off that label. My close association with Bhutto resulted in my own incarceration toward the end of the second Sharif government (1997â1999), and my opposition to General Pervez Musharraf's military dictatorship forced me to exile to the United States a few months after 9/11.

Over all these years I have seen Americans make mistakes in their dealings with Pakistan as well as in their overall foreign policy. Nonetheless, I have always been convinced that the United States remains a force for good in the world. Pakistan has benefited from its relations with the United States and would benefit even more if it could overcome erroneous assumptions about its own national security and role in the world. Instead of seeking close security ties based on false promises, Pakistan must face its history and diversity honestly, and it should be neither dependent on nor resentful of the world's most powerful nation.

As Pakistan's ambassador to the United States from 2008 to 2011, I sought to overcome the bitterness of the past in order to help lay the foundations for a long-term partnership. I studied the relations

between the United States and its other partners so as to figure out why almost all postâWorld War II US allies have found prosperity and stability through this partnership, whereas Pakistan has not. But major power centers in my own country resisted my vision of a broader US-Pakistan partnership rooted in mutual trust.

Instead of appreciating my efforts to redefine the US-Pakistan relationship through an honest appraisal of past mistakes, Pakistan's security services saw me as working for American rather than Pakistani interests. Through the media I was falsely accused of helping the CIA expand its network of spies in Pakistan, and my remarks about the transactional nature of past ties were distorted so as to suggest that I had described Pakistanis as beggars. In the end I was forced to resign amid fabricated charges that I had sought help from the US military through a dubious American businessman of Pakistani origin in order to avert a coup.