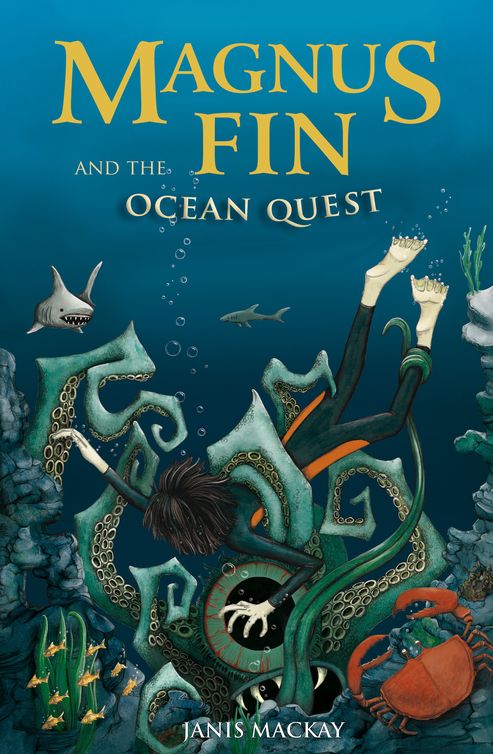

Magnus Fin and the Ocean Quest

Read Magnus Fin and the Ocean Quest Online

Authors: Janis Mackay

For Eirinn and Saul

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Chapter Twenty-nine

Chapter Thirty

Also by Janis Mackay

Copyright

Hello whoever you are,

My name is Magnus Fin.

I’m glad you picked me out of the sea. In three weeks I am eleven. I’ve got a Neptune’s cave in my room, with bottles and bits of boats and shells and funny shaped wood and treasure off sunken ships. I live beside the sea. If anybody finds this I want to have a best friend, and I want to be more brave. I want my parents to be happy like they used to be. I hope eleven is good. Maybe we will meet. Whoever finds this – we can be best friends. I have different eyes, one green and one brown, but I am fine and like I said my name is Magnus Fin.

Good luck

Magnus Fin rolled up the small sheet of paper and fed it carefully down through the bottle neck then corked the dark green glass bottle. It was ten o’clock at night but this far north come midsummer it hardly got dark. He ran down to the shore then leapt easily over the craggy rocks. When he was as far out as he could go he swung his arm once, twice, three times, then flung the old green glass bottle out to sea.

The water was smooth. The bottle hit the surface with a plop, vanished for a moment, then floated back up to the surface where the out-going tide carried it away.

Magnus Fin watched until his bottle was a tiny speck, bobbing in the distance. “Good luck,” he shouted after it, then turned and jumped from rock to rock until he was back on the sand.

Once more he turned and peered out to sea. His bottle had gone. With excitement pounding in his chest he ran back home along the shore.

“Where were you, Magnus?” his mother called from her darkened bedroom. Her voice sounded thin and wispy. Magnus Fin gently closed the front door of their small cottage and stood in the half-light of the living room.

“Just down at the sea,” he said, still panting from his run. “It’s still light.”

“And late, laddie. What else are they going to say about us, with you running about like an urchin? Come through here and let me see you for a second.” His mother’s words sounded dry and anxious coming from her darkened room. Magnus Fin, biting his nails, breathed deeply then took his ragged nail out of his mouth and stepped into his parents’ bedroom to say good night.

“It’s still so light, Mum. Sun’s still up,” he said, peering through the dim light to where he could just make out the hunched figure of his mother sitting up in bed. Red rays from the setting sun stole through a slit in the closed curtains and fell upon his mother’s ancient-looking face. Though he had looked upon his mother like this for some years now, and often in darkened rooms, it still shocked him to see how withered and lined she had become.

“I threw a message in a bottle out to sea,” he said, “that’s all.”

“Oh, did you, son? What for?”

“For fun. And – and I made a wish.”

“Good, Magnus. That’s good. We could do with wishes. Were there any waves to speak of?” his mother asked, her words slow and shaky.

“No. Sea’s still flat as a pancake,” he said, edging backwards. He wanted to be gone from this dark, sad place. He wanted to be in his own room, which he’d made into a treasure trove full of the findings he’d combed from the beach. And he didn’t want to tell his mother about his wishes. If he told her they might not come true. Everybody knew that.

“Anyone out and about?” she asked.

“No. Not down at the beach, but I could hear music. I think there’s a dance on in the village hall, Mum. I heard the band playing. You should go sometimes, you and Dad. You can still walk. You could dance; Granny told me you were a great dancer. You still could, so could Dad,” Magnus Fin said, hurt choking his voice. “You could. I don’t know why you won’t. You could …”

His mother shook her white-haired head from side to side.

“Wheesht, son. We’re better here, better staying quiet. Run off to bed now. Your dad will come through soon to say good night. Go on, laddie, off with you.”

She gave a slow wave of her hand, and Magnus Fin, muttering good night, went through to his bedroom. He wished for the millionth time that his parents

did

go to the ceilidh every Friday night in the village hall,

and

the pub,

and

the badminton and did all the other things normal

parents did.

In the quiet of his room Magnus Fin picked up the rusty bell he had found on the shore that morning. His treasures made everything better. The old bell felt heavy in his young hand. He gazed at the round rusty thing. At least it could have been a bell on a ship once, he thought, or very much hoped. A big sailing ship – or a cruise liner even – like the fancy ships he’d seen passing on their way to Orkney. He lifted it up and felt the weight of the iron. Even the bell that might have tolled on the ill-fated

Titanic

couldn’t ring away his gloomy mood. And the feeling of gloom, he knew, was because of the cruel words he’d overheard in the village that afternoon about his parents.

“Och, them?” a man had said in the shop, shaking his head, not seeing the boy behind him. “Something right funny about them!”

And Magnus Fin, though he wanted to stand up for his parents, didn’t have the courage to say anything. Instead he ran out of the shop, forgetting all about the comic and the fudge he had wanted to buy.

Now, in the peace of his own room, a hundred thoughts ran through his head.

Something right funny about them!

Thing is, the man in the shop was right. There

was

something funny about them

and

their son, and not in a ha-ha way either. And the older Magnus Fin got, the more he noticed something was wrong. Magnus Fin had, as he wrote in his message in a bottle, uncanny eyes: one green, one

brown. And as if that wasn’t uncanny enough, his pupils were not black but dark blue. And there was something else wrong with him, though he made sure no one ever saw. His feet were webbed, just slightly, between the toes.

And to top all that, his parents had a terrible affliction. They were

strange

! They weren’t hippies or Goths, geeks or organic gardeners, motorbike riders or train spotters, jail-birds or communists. No – they were much stranger than that! Ragnor and Barbara, Magnus Fin’s parents, looked ancient. I don’t mean fifty with a few grey hairs, laughter lines and double chins. No – I mean, though Magnus Fin was only ten years old, his parents looked nigh on one hundred. And what unsettled the village folk was that Ragnor and Barbara, only years before, had been young, fit and handsome. Then suddenly they had seemed to age and fade beyond their years.

Some of the villagers, thinking the aging affliction might be catching, kept well away. Of course a few friendly souls in the village came calling with catalogues or raffle tickets or toys for the boy, but even they stopped calling when Barbara refused to answer the door.

So Magnus Fin had a fairly lonely life. He was the butt of most of the jokes at school and usually stood by himself at playtime, reading a book, flicking his marbles across the ground or staring into space. He wished he was brave enough to join in the other children’s games, or stick up for his parents, but the thought of standing up to the kids who teased him the most made his knees

quake.

So at school he stood on his own, him and his strange eyes staring into space. At least the other pupils thought the “weirdo” Magnus Fin was staring into space. They didn’t know he was off at sea, under the waves, or surfing, or diving, or picking velvet crabs out of rock pools, or finding treasure from sunken ships. And when the rude man in the shop had said that very afternoon, with a sneer in his voice, “Och, them? Something right funny about them!” Magnus Fin could only bite his lip, turn on his heels and run.

Now, holding the rusty bell, he tried not to think about all of that. He heard his mother softly sobbing in the room next door, like she did most nights. He got up and went to his window. A huge moon rose over the water. Unlike his parents he never closed his curtains. He lifted the piece of rusty iron and held it up then swung it back and forth, imagining it ringing out to warn all aboard a storm was coming.

He heard his father shuffling about in the living room. Ragnor would come through soon to wish his son good night. Sleep, though, felt a long way off for Magnus Fin. Perhaps it was the light of midsummer plus the effect of the full moon, but Magnus Fin’s head was in a spin. Snatches of gossip churned around his mind, harsh words he’d overheard in the village. They all came back now, squawking like crows inside his head:

“Thon old couple down at the shore, their problem is they don’t eat meat, that’s what’s wrong with them!” That was Mrs Gow, the

butcher’s wife. “Aye, mark my words – no meat, no looks.”

“Ach! I heard they overdid the sunbathing and that’s when they started to look a hundred.” That was pasty-faced Mrs Gunn, who was a great believer in factor fifty sunscreen. “I don’t trust the ozone myself,” she had added, folding her white arms and frowning.

“Naw, naw. That’s no the real reason. The real reason is they went off to California to have face lifts and look what happened!” said wee Patsy Mackay. Magnus Fin saw her now in his mind’s eye, gasping and holding her face together as though the aging might all of a sudden come upon her and her face might drop off.

He imagined all the gossips huddled together in a sinking ship, screaming as salt water came over them and his old bell rang out their death knell.

Then he thought that was probably a bit unkind – after all, “Words don’t hurt,” as his father was forever saying. So Magnus imagined them all bundled together in a ship, getting a good old soaking instead.

It was late now, and dark. Magnus Fin’s eyelids grew droopy. He put his bell on a shelf next to his starfish then climbed into bed. His bed was a boat in which he set sail into an underwater dreamland each night. Whatever names he’d been called during the day – Alien Eyes or Walking Stick or Chicken Heart or Face Mistake – never seemed to matter as much when he was in his bed drifting off to sleep. Sleep made everything all right again. And dreams.

Before Magnus fell asleep that night his dad came in to say good night, like he always did. Ragnor lifted his son’s hands and saw that the nails were bitten down to the skin. The man with the long grey hair and leathery, lined face stroked his son’s dark hair and whispered kindly, “Try not to worry, lad; this is how we are now.”

“But I get called names, Dad. I don’t like it.”

“You know what they say about sticks and stones breaking your bones and names not hurting you?”

“Well, it’s not true,” said Magnus Fin, “and I am scared of them.” But his voice was drowsy now. His father’s words drifted into his half-sleep as though they were coming from a long way off.

“It could be worse,” Ragnor continued, stroking his son’s hand. “Folks will talk and call you names. Some folk are just like that. They don’t know better. Dinny heed them, Fin. Be proud of who you are. It’s no bad thing to be different. You’re special, my lad; if only you knew just how special you are. For now, just get on with life as best you can. Good night, Fin.”

As Ragnor left the room he muttered something about the sea and it giving Fin courage … but by that time Magnus Fin was sound asleep.