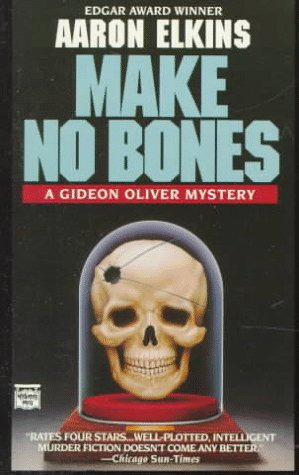

Make No Bones

Authors: Aaron Elkins

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Police Procedural, #Crime, #Thrillers, #Medical, #General

Oregon’s anthropologist-sleuth Gideon Oliver and his park-ranger wife Julie are attending a conference of anthropologists at Whitebark Lodge, where ten years before Professor Albert Evan Jasper, undisputed top dog in the field, died in a fiery bus crash, at the end of another conference and amid rather mysterious circumstances.

Several of the participants in that meeting are once again at Whitebark—one of them is Associate Professor Harlow Pollard, whose bludgeoned body is found in his cottage—the climax of a series of strange events seemingly tied to the past. Gideon cleverly solves the crucial element in that murder—the liveliest part of a sluggish story heavily laden with technical lore, all too rarely lightened with the author’s finely honed sense of humor.

A Novel by

Aaron Elkins

Copyright © 1991

by Aaron Elkins

The idea behind Make No Bones sprang from the wonderful “Mummies, Mayhem & Miseries” exhibit put on by the San Diego Museum of Man under Curator of Physical Anthropology Rose Tyson. Later, Dr. William D. Haglund, Chief Investigator, King County Medical Examiner’s Office, took, a morning to help me work out a “perfect” murder (and then helped me solve it). Sergeant of Detectives Greg Brown filled me in on how things work in Deschutes County, Oregon. Dr. Ted Rathbun of the Anthropology Department, University of South Carolina, provided insight into the trickier aspects of reconstructing faces from skulls. Dr. Walter H. Birkby of the Anthropology Department, University of Arizona, spent a sunny hour beside a swimming pool cheerfully filling me in (so to speak) on the ins and outs of burial and exhumation.

I am extremely grateful to the tolerant and good-natured scientists of the Mountain, Desert & Coastal Forensic Anthropologists, who welcomed me among them at their 1990 annual meeting, and in particular to Dr. J. Stanley Rhine of the Department of Anthropology, University of New Mexico, who first suggested the idea of a murder set at a gathering of forensic scientists, provided technical assistance at several points along the way, and helped me in even more ways than he knows.

From: Miranda Glass, Curator of Anthropology, Central Oregon Museum of Natural History.

To: Members of the Western Association of Forensic Anthropologists.

Subject: Sixth Biennial WAFA Conference

Esteemed Fellow Body-Snatchers:

June 16-22, the week of our eagerly anticipated bone bash and weenie roast, is fast approaching. As this year’s host I hereby bid you a genial welcome.

Fittingly enough, this year’s enlightenment and jollification will be held where it all started: the decaying but still scenic Whitebark Lodge…

Nelson Halston Hobert, president of the National Society of Forensic Anthropology, Distinguished Services Professor of Human Biology at the University of Northern New Mexico, and at sixty-four the undisputed dean of American forensic anthropologists, frowned as he read the letter. The breakfast dishes had been cleared to one side, his third cup of coffee was freshly poured, and his morning pipe was newly lit and fragrant. His posture was one of thoughtful repose, his mood benign but troubled.

“Damn,” he murmured, “that’s going to stir up a few old anxieties.”

Across the table from him his wife appraised him and found him wanting.

“You have something in your beard,” she told him in a matter-of-fact tone. “Banana bread, I believe.”

“Mm,” he said abstractedly, “I suppose.” He continued to read.

“Honestly,” Frieda Hobert said, not unfondly. She reached across the pile of mail and used the tip of her folded napkin to dab the offending crumb from her husband’s bristly gray beard. Another flick removed a shred of tobacco from his old brown jogging suit. She looked him over once more, this time approvingly, and sat back satisfied.

If Hobert was aware of these attentions he gave no sign. “Miranda’s set up this year’s WAFA meeting,” he told her. “The week of June sixteenth.”

“You can’t make it. Pru is getting married on the sixteenth. In Fort Lauderdale.”

“I know, but couldn’t I—”

“Absolutely not. You were rooting around in Ethiopia when Vannie was married. You’re not going to miss this one.” She dipped her chin and looked at him over the top of her plastic-rimmed glasses so he would know she meant it.

“No, I suppose I shouldn’t,” he said reluctantly. “Well, we could see about flights out of Fort Lauderdale that evening—”

“Nellie, I am not sitting up in an airplane all night long, not after what is bound to be an exhausting day. We can leave the next day, after a good night’s sleep. Believe me, WAFA will manage to survive without you for a day or two.

Nellie scratched his gleaming scalp and frowned. “Normally I’d have no doubt about that. But…all right, we’ll get a flight the next day.”

The “we” was a foregone conclusion. For a dozen years, ever since she’d quit her job teaching, Frieda had accompanied him to his conferences and conventions. Occasionally this was annoying, but not often. She was extremely helpful on his trips, making airplane and hotel reservations, arranging his appointment calendar, even packing his clothes, and relieving him of a hundred bothersome details. He had become, he realized, a substitute for the generations of grade-school kids she’d nurtured for twenty-five years, but that was all right with Nellie. If not him, then who?

Besides, the truth was that he liked having her with him, liked starting and ending the day with her. They’d been married a long time now, and although there were plenty of ups and downs, a day without Frieda put him off his stride, made him feel not quite whole.

“You know why you need me?” she’d once asked when they were discussing the subject. “Because without me you tend to forget you’re an august personage and have to behave accordingly.”

Well, she certainly had a point there. It wasn’t easy remembering you were an august personage.

She lowered the envelope she was opening. “What do you mean,

normally

you’d have no doubt?”

“Frieda,” he said, “Miranda’s arranged the meeting for Whitebark Lodge.”

“Whitebark Lodge!” Her expression was pained. “What an absolutely rotten idea. What on earth was she thinking of?”

“Well, you have to remember, Miranda wasn’t there the night that…well, the night of the party. No guilty memories for her.”

“I hardly think guilt is the right word, Nellie. How could any of you even dream how it was going to turn out? You can’t hold yourselves responsible for Albert Evan Jasper’s—for what happened to him.”

As she spoke he nodded along with her, drawing on his pipe. “I know, Frieda, I know.” It wasn’t the first time he’d heard her say it, and in general he agreed with her.

“Still,” she said, tapping the envelope against her longish chin, “it’s going to stir up some rather unpleasant associations, isn’t it?”

“That’s for damn sure.” Nellie swallowed the last of his coffee, sucked hard on his pipe to make sure it was still lit, and abruptly stood up, not wanting to go into it with her just then. “It’s not even nine, and I’m not due at school until one I’m going to put in the thyme and cotoneaster out front. What do you think of that?”

“I’m utterly astounded, my dear. They’ve only been sitting out there three weeks.”

One week, actually, but that was Frieda for you. She enjoyed her little digs. Kneeling in the sun, working from his knees at a lazy pace, Nellie mixed the potting soil with earth from one of the planting holes in the prescribed three-to-one ratio.

“In the magnificent fierce morning of New Mexico,” D. H. Lawrence had written, “one sprang awake, a new part of the soul woke up suddenly, and the old world gave way to the new.”

If you asked Nellie, Lawrence had gotten it wrong. For him the high desert morning was relaxing, not energizing; very nearly anesthetic, in fact. The thin, dry air, the crisp, brilliant light, the rolling, open, pinyon-dotted foothills of the Sangre de Cristos, all made him feel sleepy and content, as sleek as a pampered house cat. Sleek and reflective and, on this particular morning, a shade melancholy.

He was reflecting on the first WAFA meeting, ten years earlier, as he worked the soil. “Rather unpleasant associations,” Frieda had said, and she’d been putting it mildly. Damn unpleasant was the way he would put it. What else could you call it when you’d been responsible, no matter how unintentionally, for the death—the violent, unnecessary death—of the man to whom you owed very nearly everything important you had?

He leaned back on his heels, trowel at rest. Miranda’s letter would have gone out to all forty or so WAFA members. For four of them—and only four—the mention of Whitebark Lodge would create those same “rather unpleasant associations.”

He wondered what they were thinking about right now.

Callie Duffer was thinking about—or at least talking about—the self-esteem needs and personal-growth potential of an anthropology student named Marc Vroom, who was in considerable danger of flunking out of Nevada State University in his first graduate semester. As departmental chair, she felt she was required to declare her opinions.

“Surely you see,” she told the three faculty members gathered in her office, “that failing this young man would solve none of his problems.”

“Well, it’d go a long way toward solving mine,” Harlow Pollard grumbled.

Callie swallowed down a surge of irritation. Had he said it with a hint of humor, even sardonic humor, she might have smiled. But Harlow was about as humorous as a codfish, and not so very much quicker on the uptake. Still, what was the point of getting annoyed? The man was to be pitied, a simplistic dinosaur incapable of comprehending the new dynamics of the educational suprasystem and the role of academics as change-agents. Poor Harlow still thought that he was there to teach anthropology, period. A living argument, Callie thought, against the tenure system.

Marge Harris, one of the younger instructors, tentatively waggled her fingers for attention. “Callie,” she said hesitantly, “we all understand how dedicated you are to the concept of the university as a social support network—”

Harlow made an unpleasant strangled sound.

“—but you haven’t had him in any of your classes,” Marge went on. “He’s constantly unprepared. When he’s not argumentative he’s flippant. When we try to point out what we expect of

him

, he treats it as a huge joke—”

“Ah!” Callie said, seizing on this, “what

we

expect of

him

. Couldn’t that be the problem right there? Have we tried to attune ourselves to

his

needs? Have we taken the trouble to understand where

he’s

coming from?”

A telling thrust, Callie thought, but the three of them just sat there, dumb and resisting. You’d think that at least the younger ones would grasp the importance of structural flexibility when you were dealing with a dysfunctional—

“Can I tell you what happened Friday?” Harlow said, face down, mumbling, talking to all of them. “I was giving my 304 midterm. Mr. Vroom came in fifteen minutes late, sat there five minutes, handed in his paper, and left. Do you know what he wrote?”

“No, what did he write, Harlow?” Callie said with a wooden-lipped attempt at a smile. How strange it was, when you came to think of it, that almost everything she said to Harlow Pollard required this granite-willed attitude of indulgence on her part. At fifty-three, he was nine years her senior, and once upon a time he had been her major professor. She had gotten her Ph.D. under him, right here at Nevada State, and started immediately as a temporary lecturer when he was already a fully tenured associate professor.

And now, she thought, idly fingering the buttery brown leather arm of the chair she’d inherited when she’d taken over the department, now here she was a dozen years later, a full professor and department chair to boot. And soon to be dean of faculty, if she didn’t screw things up. And poor, plodding, shortsighted Harlow? Harlow was still an associate professor. He would be an associate professor when he retired. (Soon, God willing.)

“Well, here’s what he wrote,” Harlow droned on. “’Sorry, prof, not my day.’ This was in big block letters, then he drew one of those, what do you call them, one of those Happy Faces, and wrote ‘Have a nice day.”

He looked up, thick-witted and impenetrable. “Can anyone tell me what to make of that?”

Callie was weary of the conversation, but she leaned forward with what she hoped looked like eagerness. “But can’t you see that, looked at in the right way, that’s his attempt—faltering, tentative, to be sure—to open up communication? This is our chance to respond, to show him that we care, that we can be nurturing as well as censuring.”

“Nurturing…?” Harlow echoed opaquely. He really, truly didn’t get it, didn’t even understand the words. The others weren’t much better.