Making Artisan Cheese (5 page)

Read Making Artisan Cheese Online

Authors: Tim Smith

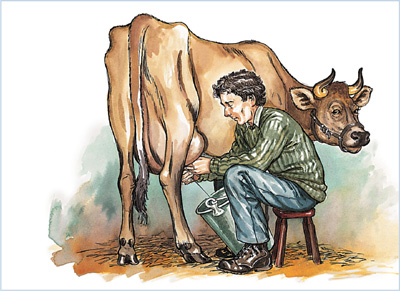

Jersey cows are considered by many artisans to be the best breed for cheese making due to the high butterfat content of their milk.

Cow’s milk cheeses are flavorful, with a creamy consistency that varies depending on the cream content of the milk.

Cow’s Milk

In the Western world, the vast majority of cheeses produced and consumed are made with cow’s milk. This is primarily due to historical influences (cows were brought over on the boats for the settlement of the Jamestown colony in 1606), and the fact that the climate and terrain are suitable to their nature. Cows require large tracts of land, abundant vegetation, and temperate climates, all of which exist in North America. Their milk is rich and creamy, with high moisture content and large fat globules that rise to the surface. These qualities, combined with a firm casein structure, make it easy to use for cheese making. It is important to also remember that there are variations in milk quality within the different breeds of cattle. Holsteins, the most popular breed for producing drinking milk, make milk with a fat content of 3.5–4%, whereas the creamy milk of Jersey cows—which are preferred by cheese makers—tops out at 5.4%.

Goat’s Milk

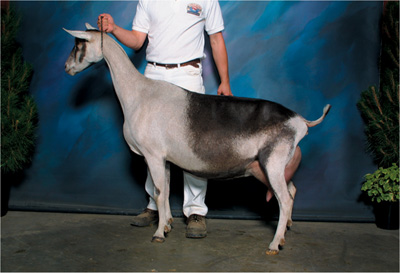

Although goat’s milk cheeses are a relatively recent phenomenon in the United States, they are very common in many parts of the world. Goats are hardy creatures that can survive in extreme climates with scant, poor-quality vegetation for food. Unlike cows, which have a specific diet, goats will eat a varied diet with little fanfare. Goat’s milk is partially homogenized (meaning that it contains small fat particles held in suspension in the milk), although there is some cream separation. It also has smaller fat globules compared to those of cow’s milk. Consequently, goat’s milk cheeses have a smoother, softer texture than cow’s milk cheeses. Goat cheeses have a distinctive tangy, some even say gamey, flavor.

Goat’s milk cheeses have a creamy consistency and a tangier flavor than cheeses made from cow’s milk.

The Swiss Alpine breed of goats, such as the 2002 Grand Champion show winner shown here, is the most popular variety of goat for cheese makers due to its generous milk production.

Sheep’s Milk

Sheep are sturdy animals that can live in areas that no cow would dare consider. Because of their thick, wooly coats, they can survive in some of the harshest conditions. It is for this reason that sheep’s milk cheeses tend to come from the more challenging regions of the world—windy, rocky climates with little vegetation. Think of the arid regions of Greece or Sicily, and you will get the idea. Sheep’s milk is an amazing product. Fully homogenized, it is the densest of the three milks. It is interesting to note that whereas a cow will produce considerably more milk compared to a sheep (ten gallons versus one quart per day), the amount of solids is almost identical. Sheep’s milk cheeses are dense with oil and butterfat, which come to the surface of the cheese, making for a rich and flavorful product. Although some of the world’s great cheeses are made from sheep’s milk, there are few, if any, sheep dairies in the United States. This prized commodity is a tough find for the home cheese maker (see Resources,

page 173

).

Sheep’s milk cheeses—and sheep’s milk itself—although flavorful and creamy, are harder to find than cow’s and goat’s milk and cheeses, because sheep produce less milk. A breed native to Germany, East Frisian sheep, shown here, are preferred for their comparatively high milk production.

Artisan Advice

In spite of the fact that they produce only about a quart (or liter) of milk a day, sheep were the first animals milked by people. Sheep were milked 3,000 years before cows.

This pepper jack was derailed because the curds were not pressed at a sufficient pressure for them to set properly. If your cheese is pressed properly, and it still refuses to set, then immerse the cheese in 100°F (38°C) water for one minute, then press for thirty minutes, to encourage the process.

What Can GoWrong

When it comes to making cheese, moderation is the key, beginning with warming the milk. Whether you are pasteurizing raw milk or warming pasteurized milk to prepare it for making cheese, do so very slowly. Keep a thermometer in the pan and consult it often. If you heat the milk too quickly, the rapid increase in temperature will kill the helpful bacteria and enzymes that convert the milk to cheese.

A cow that has a diet rich in fresh, wild grasses will produce richer, more flavorful milk.

How Grazing, Season, and Geography Affect Milk

Whatever an animal eats will have a direct effect on the quality of its milk, which in turn affects the quality of the cheese made from it. So in addition to the breed and the type of animal, a cheese maker must continually consider the external factors that will affect the diet of the animal.

Take grazing as an example. A cow fed a diet rich in fresh, wild grasses will produce richer, more flavorful milk. The milk from animals that graze on wild grasses contains lower cholesterol and higher omega-3 acid ratings than the milk of their penned, silage-fed kin—proof that a happy grazer is a healthy grazer. Conversely, if the cow is fed dried, stale grasses and fermented silage, the flavor of the milk will suffer, as will the cheese.

The time of year also plays an important role in cheese making. Winter is not considered the ideal season for cheese making, especially in cold climates where cows must eat silage. Where animals graze also comes into play. If cows are situated in a coastal region, it is more than likely that the milk, and consequently the cheese, will have a salty note due to the salt that sea breezes deposit on the grasses.

All of these influences can best be summoned up by the French word

terroir

. Most dictionaries translate this word as “soil” or “country,” which is not entirely accurate. Terroir can best be described as the soul of a particular spot on earth. A particular terroir can be arid or damp, mountainous or flat, cold or hot—each terroir is unique. This is one explanation for the different characteristic flavors of many regional cheeses.

Artisan Advice

Cows milked in the evening give milk that’s higher in fat content and better for making cheese than milk extracted in the morning.