Making the Connection: Strategies to Build Effective Personal Relationships (Collection) (64 page)

Read Making the Connection: Strategies to Build Effective Personal Relationships (Collection) Online

Authors: Jonathan Herring,Sandy Allgeier,Richard Templar,Samuel Barondes

Tags: #Self-Help, #General, #Business & Economics, #Psychology

Having laid out his list, Franklin immediately got started in a methodical way. Recognizing that he could not acquire these virtues all at once, he set to work on them one at a time. Believing that “the previous acquisition of some might facilitate the acquisition of certain others,” he arranged them in that particular order: “Temperance first, as it tends to procure that coolness and clearness of head, which is so necessary where constant vigilance was to be kept up, and guard maintained against the unremitting attraction of ancient habits, and the force of perpetual temptations.” What Franklin particularly had in mind when starting with temperance

was to stop drinking so much at pubs, which had led him astray in the past. So for the first week of his program, he concentrated on temperance. He then continued down the list, completing all 13 in a quarter of a year and then starting over again. Day by day he kept a record in a tiny book in which he “might mark, by a little black spot, every fault I found upon examination to have been committed respecting that virtue.”

He found this daily record keeping both informative and rewarding. On the one hand, he was surprised to be “so much fuller of faults than I had imagined”; on the other hand, he was pleased with “the satisfaction of seeing them diminished.” But despite his progress, Franklin kept returning to the program from time to time and always carried his list with him, even in old age. In assessing this lifetime of practice, he concluded, “[T]hough I never arrived at the perfection I had been so ambitious of obtaining, but fell far short of it, yet I was, by the endeavor, a better and happier man than I otherwise should have been if I had not attempted it.”

Franklin had good reasons to be satisfied with the results. Within a decade of setting his self-improvement program in motion, he had built a printing and publishing business that would leave him well off. With this newfound financial security, he was able to pursue his interests in science and statesmanship, which led to brilliant achievements and worldwide fame. But even more than these trappings of success, Franklin was grateful for “that evenness of temper, and that cheerfulness in conversation” that he attributed to his devoted practice of “the joint influence of the whole mass

of virtues, even in the imperfect state he was able to acquire them.” So convinced was he of the value of his program that he kept toying with the possibility of publishing a self-help book called

The Art of Virtue,

to supplement what he had already explained in his

Autobiography.

Separating Character and Personality

Some of Benjamin Franklin’s ideas about personality have a great deal in common with those I have discussed so far. He, too, recognized that people’s individual differences could be thought of in terms of a set of traits. He, too, recognized that they are influenced by genes (which he called “natural inclination”) and by environmental factors such as culture (“custom”) and peers (“company”). And, being a lover of lists, Franklin would have been happy to organize his thoughts about his basic personality tendencies in terms of the Big Five.

Had Franklin assessed his own Big Five traits while drafting the self-improvement plan, he would have found much he was pleased with. The most obvious was his very high Extraversion, especially gregariousness, enthusiasm, and good humor. Also obvious was his self-confidence and freedom from negative emotions, signs of low Neuroticism, and his curiosity and creativity, signs of high Openness.

But Franklin wasn’t particularly interested in these characteristics, which he considered part of his God-given temperament and which he took for granted. Instead, he was

raised to believe that the most important part of personality was its moral aspect, which was acquired through personal effort. To Franklin, this meant that he could build his own character by working on those virtues that seemed in most need of improvement. He also believed that good character was his ticket to both productivity and happiness.

Franklin was not alone in this belief. Through the ages philosophers and religious leaders have encouraged the development of good character. What mainly distinguished Franklin’s ideas from those of his predecessors was his elaborate practical method for self-improvement. Instead of simply singing the praises of a series of virtues, Franklin wrote out a personal to-do list and a step-by-step plan for upgrading one virtue at a time. Recognizing that backsliding is natural, he committed himself to repeated practice. Recognizing that some virtues, such as humility and order, were particularly hard for him to achieve, he decided to lower his standards and cut himself some slack. The result was a program that was explicit, realistic, and, as he looked back on it, seemingly effective.

Over the years, Franklin’s ideas about character attracted many admirers. He also had some critics who disagreed with the list of moral virtues he chose to emphasize. But despite such disagreements, most Americans who lived in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries shared the view that character was the most significant part of personality—and the part that could be improved through conscious effort.

Nevertheless, when scientific studies of personality were getting underway in the 1930s, the decision was made to separate the concept of character from the concept of personality. A leading proponent of this separation was Gordon Allport, whose research on categorizing personality traits I described in

Chapter 1

. Having been raised in a pious Midwestern Methodist family, Allport recognized that his personal values were not shared by everyone and had no place in his scientific work. As he put it:

Whenever we speak of character we are likely to imply a moral standard and make a judgment of value. This complication worries psychologists who wish to keep the actual structure and functioning of personality free from judgments of moral acceptability .... Now one may, of course, make a judgment of value concerning a personality as a whole, or concerning any part of personality: “He is a noble fellow.” “She has many endearing qualities.” In both cases we are saying that the person in question has traits which, when viewed by some outside social or moral standards, are desirable. The raw psychological fact is that the person’s qualities are simply what they are. Some observers (and some cultures) may find them noble and endearing; others may not. For this reason—and to be consistent with our own definition—we prefer to define

character as personality evaluated;

and

personality,

if you will, as

character devaluated.

3

So when Allport scanned the dictionary to collect the raw material for a study of personality traits, he excluded words such as

virtuous

and

noble

that make moral judgments. Others who developed the Big Five followed his lead. Although they named some facets with moral-sounding words such as

altruism

and

modesty,

they insisted on using them in a purely descriptive way without expressing opinions about the merits of high or low scores.

The clinicians who defined the Top Ten patterns in DSM-IV also tried to withhold moral judgments. Trained to be open-minded about their patients’ behavior, they were guided by a professional code of conduct that used functional concepts such as adaptive and maladaptive rather than moral ones such as good and bad. Their functional view recognizes that there may be advantages and disadvantages to degrees of expression of different traits and patterns, and that any of them can be adaptive in certain circumstances.

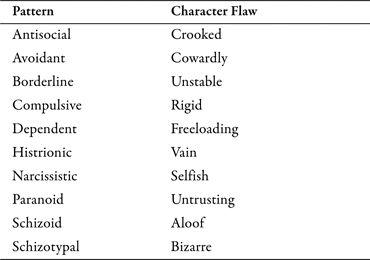

But even though this functional view appears morally neutral, it recognizes that certain patterns are worth singling out because they tend to bring grief to those who express them and to those they deal with. In fact, the negative reaction to these troublesome patterns is the main reason they are considered maladaptive. And because such negative reactions are frequently expressed as moral judgments, it should come as no surprise that features of the Top Ten are also spoken of as “character flaws” in ordinary conversation. To emphasize this point, I have listed examples in

Table 5.1

.

Table 5.1 The Top Ten as Character Flaws

Identifying maladaptive patterns as character flaws isn’t just an idiosyncratic judgment. There appears to be a widespread preference for people who are honest, courageous, emotionally stable, flexible, productive, modest, generous, trusting, sociable, and only moderately quirky—the sorts of individuals with none of the ten flaws on the list. Put simply, behaviors that we consider signs of good character may also be adaptive because most of us recognize them as being desirable, prefer to deal with those who express them, and tend to stay away from those who do not.

We make such judgments all the time. And we place heavy emphasis on character in our intuitive assessments of people. Although our minds are naturally tuned to notice all of a person’s major traits, those traits that really grab our attention and dominate our thinking have a moral flavor that is linked to emotional reactions.

4

Why is this so? Why do traits with a moral quality have such a powerful effect on us? Is this just a reflection of the cultural influences that Allport emphasized? Or does something more elemental and deep-seated about them beg for explicit attention? Might there be moral instincts that incorporate specific emotions into our assessments of people?

Moral Instincts and Moral Emotions

The idea that there are moral instincts is not new, and one of its main proponents was none other than Charles Darwin. Having recognized that instinctive social behaviors of animals evolved by natural selection, Darwin concluded that the same was also true for humans and that this process contributed to the development of our moral feelings and actions. As he put it in

The Descent of Man,

“any animal whatever, endowed with well-marked social instincts, the parental and filial affections being here included, would inevitably acquire a moral sense or conscience, as soon as its intellectual powers had become as well, or nearly as well developed, as in man.”

5

To grasp the significance of Darwin’s suggestion, it helps to translate it into the language of genes. What Darwin was saying is that social and moral instincts, and the brain circuits that control them, evolved in the same way as other innate mental processes of thinking and feeling—by the natural selection of relevant gene variants—and that a reason the human genome contains many gene variants that promote social and moral instincts is that such variants contribute to fitness.

In the case of those instincts that lead people to nurture their children and to be generous to other close kin, the selective advantage is easily identified: It is the perpetuation of shared genes, the great driving force of evolution. But why would our conscience and social instincts also impel us to be generous to strangers? Given that fitness is determined by competition between individuals, shouldn’t the genes that contribute to selfishness be the ones that are naturally selected? What forces would favor the selection of the genes and psychological mechanisms that restrain selfishness and promote what we call moral behavior?

A persuasive answer, which was proposed most forcefully by Robert Trivers,

6

is that moral instincts—the instincts that lead us to behave in ways that benefit other individuals or the general social order—evolved because they also benefit those who express them. Put simply, primitive forms of these instincts, such as the cautious extension of generosity to strangers, led to the selection of people who returned the favor. The mutual benefits of such reciprocal altruism—doing favors for others so that they will do favors for you—is believed to have been one driving force behind the natural selection of gene variants that contribute to morality.

7

As with other instincts, such as our instinct to speak, scientists believe that the instinct to reciprocate evolved by modifications of brain circuits that had already become established for other reasons. In the case of the moral instincts, Frans de Waal

8

suggests that they may have had their beginnings in circuits for emotional contagion. One example de Waal gives of this primitive form of empathy is the

instantaneous spread of fear from a bird that senses danger through the whole grazing flock, which immediately takes to the air. Another is the spread of crying from one infant in a newborn nursery to all the other infants in the room. In de Waal’s view, such emotional contagion may have been the basis for the next type of empathy, which he calls sympathetic concern. An example is the mutual embrace of a group of infant monkeys when one of them is in distress. From these simple beginnings, new emotional brain circuits appear to have evolved

9

that immediately reward both the donor and the recipient of altruistic behavior with positive feelings.