Male Sex Work and Society (16 page)

Read Male Sex Work and Society Online

Authors: Unknown

Tags: #Psychology/Human Sexuality, #Social Science/Gay Studies, #SOC012000, #PSY016000

The rough camera work, 30-minute shots, and extended dialog allow

My Hustler

to “closely [resemble] a documentary film in its cinema verité style—a documentary of homosexual desire at one historical moment” (Escoffier, 2009, p. 26). This interest in documentary style has been praised by Joe Thomas (2000) for its “open representations of the eroticized male body presented within the relatively safe (for closeted gay viewers) context of avant-garde art” in a way that has been directly linked to the “formal and narrative models [of] the early days of gay porn” (p. 69). Early “porn filmmaking,” Jeffrey Escoffier (2009) explains, “included a strong documentary impulse—ultimately documenting and authenticating male sexual arousal and release” (p. 26), a goal that later became key to the New Queer Cinema movement as well.

My Hustler

to “closely [resemble] a documentary film in its cinema verité style—a documentary of homosexual desire at one historical moment” (Escoffier, 2009, p. 26). This interest in documentary style has been praised by Joe Thomas (2000) for its “open representations of the eroticized male body presented within the relatively safe (for closeted gay viewers) context of avant-garde art” in a way that has been directly linked to the “formal and narrative models [of] the early days of gay porn” (p. 69). Early “porn filmmaking,” Jeffrey Escoffier (2009) explains, “included a strong documentary impulse—ultimately documenting and authenticating male sexual arousal and release” (p. 26), a goal that later became key to the New Queer Cinema movement as well.

Interestingly, these same concerns (and the work of Andy Warhol specifically) played heavily into the early films of Pedro Almodovar and the aesthetics of

La Movida

, Spain’s post-Franco youth movement of the 1970s and 1980s (D’Lugo, 2006, p. 18),

7

and in the work of Rainer Werner Fassbinder and the New German Cinema of the same time period. In fact, Almodovar’s “Warholesque interest in … male prostitutes and drag queens” (p. 19) has been cited as one of the main reasons for his “meteoric rise to international prominence,” in that it was able to “align the gay scene in Madrid with Warhol’s New York of the previous decade” (p. 19).

8

Fassbinder, whose film

Fox and His Friends

(1975) deals with male sex work directly,

9

also has been viewed in relation to Warhol’s work. In a 1975 review, Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson wrote, “It’s interesting that the true inheritors of early Warhol, the Warhol of

Chelsea Girls

and

My Hustler

, are in Munich” (pp. 5-6). They point to this “inheritance” in Fassbinder specifically, in that both Fassbinder’s and Warhol’s films “sprung out of a camp sensibility” that includes an appetite “for the outlandish, vulgar, and banal in matters of taste, the use of old movie conventions, a no-sweat approach to making movies, moving easily from one media to another, [and] the element of facetiousness and play in terms of style” (pp. 5-6), a connection that later was made explicit when Warhol crafted the poster for Fassbinder’s last film,

Querelle

, in 1982. In this way, the shift in how male sex workers were represented in highly acclaimed art cinema produced outside the United States was very much tied to the New York underground film scene and, in particular, the work of Andy Warhol.

La Movida

, Spain’s post-Franco youth movement of the 1970s and 1980s (D’Lugo, 2006, p. 18),

7

and in the work of Rainer Werner Fassbinder and the New German Cinema of the same time period. In fact, Almodovar’s “Warholesque interest in … male prostitutes and drag queens” (p. 19) has been cited as one of the main reasons for his “meteoric rise to international prominence,” in that it was able to “align the gay scene in Madrid with Warhol’s New York of the previous decade” (p. 19).

8

Fassbinder, whose film

Fox and His Friends

(1975) deals with male sex work directly,

9

also has been viewed in relation to Warhol’s work. In a 1975 review, Manny Farber and Patricia Patterson wrote, “It’s interesting that the true inheritors of early Warhol, the Warhol of

Chelsea Girls

and

My Hustler

, are in Munich” (pp. 5-6). They point to this “inheritance” in Fassbinder specifically, in that both Fassbinder’s and Warhol’s films “sprung out of a camp sensibility” that includes an appetite “for the outlandish, vulgar, and banal in matters of taste, the use of old movie conventions, a no-sweat approach to making movies, moving easily from one media to another, [and] the element of facetiousness and play in terms of style” (pp. 5-6), a connection that later was made explicit when Warhol crafted the poster for Fassbinder’s last film,

Querelle

, in 1982. In this way, the shift in how male sex workers were represented in highly acclaimed art cinema produced outside the United States was very much tied to the New York underground film scene and, in particular, the work of Andy Warhol.

While early films like

My Hustler

were groundbreaking in their representations of male sex workers, it was the release of

Midnight Cowboy

in 1969 that marked the first major Hollywood film (outside of the work of Tennessee Williams) to both feature male sex workers as main characters and allow them to fulfil their job description.

Midnight Cowboy

also was influenced by the work of Andy Warhol; in fact, director Schlesinger asked Warhol to make a cameo appearance in the film. As Warhol describes it, “Before I was shot, they’d asked me to play the Underground Filmmaker in the big party scene and I’d suggested Viva [one of the regulars in Warhol’s Factory] for the part” (Warhol & Hackett, 1980, p. 352). As Jody Pennington (2007) notes, “Among the novel qualities of many American films made during the period known as the Hollywood Renaissance,” of which

Midnight Cowboy

was a part, “was the routine inclusion of sexual behavior the Production Code had forbidden” (p. 52).

Midnight Cowboy

came at a time when Hollywood filmmakers were reacting to new freedoms that the studio system previously had limited due to the code. Thus it follows that subject matter from this postcode period that previously would have been unacceptable would emerge in film after a new rating system (the ratings G, M, R, and X) was established in 1968 (Casper, 2011, p. 119). Emphasizing the impossibility of creating a film like

Midnight Cowboy

during the code period, the film received an X rating.

10

My Hustler

were groundbreaking in their representations of male sex workers, it was the release of

Midnight Cowboy

in 1969 that marked the first major Hollywood film (outside of the work of Tennessee Williams) to both feature male sex workers as main characters and allow them to fulfil their job description.

Midnight Cowboy

also was influenced by the work of Andy Warhol; in fact, director Schlesinger asked Warhol to make a cameo appearance in the film. As Warhol describes it, “Before I was shot, they’d asked me to play the Underground Filmmaker in the big party scene and I’d suggested Viva [one of the regulars in Warhol’s Factory] for the part” (Warhol & Hackett, 1980, p. 352). As Jody Pennington (2007) notes, “Among the novel qualities of many American films made during the period known as the Hollywood Renaissance,” of which

Midnight Cowboy

was a part, “was the routine inclusion of sexual behavior the Production Code had forbidden” (p. 52).

Midnight Cowboy

came at a time when Hollywood filmmakers were reacting to new freedoms that the studio system previously had limited due to the code. Thus it follows that subject matter from this postcode period that previously would have been unacceptable would emerge in film after a new rating system (the ratings G, M, R, and X) was established in 1968 (Casper, 2011, p. 119). Emphasizing the impossibility of creating a film like

Midnight Cowboy

during the code period, the film received an X rating.

10

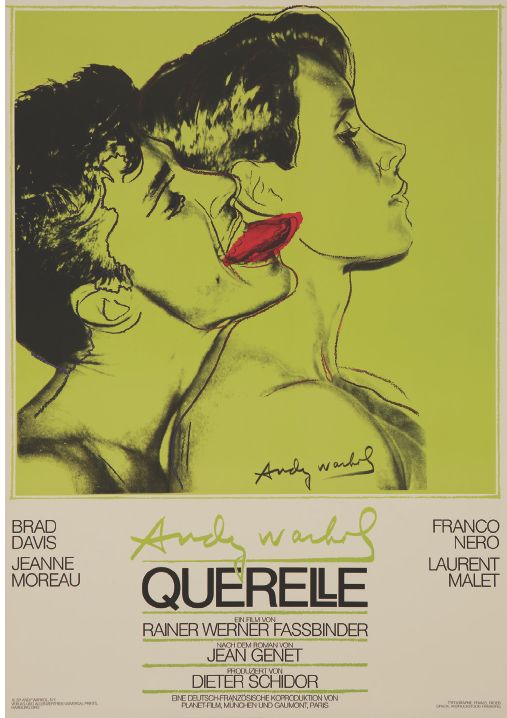

FIGURE 3.3

Andy Warhol created this movie poster for

Querelle

. He tied a shift in how male sex workers were represented in highly acclaimed art films produced outside the United States to the New York underground film scene, and to his own work in particular.

Querelle

. He tied a shift in how male sex workers were represented in highly acclaimed art films produced outside the United States to the New York underground film scene, and to his own work in particular.

Reproduced with permission from the Artists Rights Society, licensor of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. Copyright © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society, New York.

This opportunity to present subject matter that was previously unacceptable did not go unnoticed at the time. Expressing his frustration and jealousy about

Midnight Cowboy

, Warhol (Warhol & Hackett, 1980) argued that what he and the New York underground film scene originally had to offer

Midnight Cowboy

, Warhol (Warhol & Hackett, 1980) argued that what he and the New York underground film scene originally had to offer

was a new, freer content … But now that Hollywood—and Broadway, too—was dealing with those same subjects, things were getting confused … I realized that with both Hollywood and the underground making films about male hustlers—even though the two treatments couldn’t have been more different—it took away a real drawing card from the underground.” (p. 353)

“Perverse” Hustlers

Midnight Cowboy

, which starred Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman as two sex workers living on the streets of New York, reflects a complex understanding of male sex workers, presented most often in flashbacks to Joe Buck’s (Voight) past. Yet the film also reflects the sense that homosexuality is perverse, which echoes the medical and sociological writings of the 1930s.

Midnight Cowboy

is a dramatic break from

My Hustler

, in that it presents the male sex worker in a way that he had never been seen before—as a central character in a Hollywood film—while maintaining much of the stigma that had surrounded the male sex worker for decades.

, which starred Jon Voight and Dustin Hoffman as two sex workers living on the streets of New York, reflects a complex understanding of male sex workers, presented most often in flashbacks to Joe Buck’s (Voight) past. Yet the film also reflects the sense that homosexuality is perverse, which echoes the medical and sociological writings of the 1930s.

Midnight Cowboy

is a dramatic break from

My Hustler

, in that it presents the male sex worker in a way that he had never been seen before—as a central character in a Hollywood film—while maintaining much of the stigma that had surrounded the male sex worker for decades.

It is noteworthy, then, that the sociological and scientific discourse on male sex work during the 1960s and 1970s also had an interest in specific case studies of male prostitutes. Whereas

Midnight Cowboy

presented the face of male sex work as Joe Buck, John Scott (2003) notes that much of scientific discourse from the same period “was composed largely of individual case studies that sought to extract specific details concerning the aetiology of male prostitution and the identity of the male prostitute” in a way that “understood male prostitution in terms of sociopathology” (p. 186).

Midnight Cowboy

engages the subject of male prostitution similarly. By focusing on one specific sex worker, the film acts as a sort of case study, and through its use of flashbacks to childhood and adolescent trauma,

Midnight Cowboy

works to get at the etiological roots of male sex work. By using flashbacks to childhood trauma in moments of present trauma, the film creates a link that posits Joe Buck’s past traumas as the inciting events that determined his current occupation.

Midnight Cowboy

presented the face of male sex work as Joe Buck, John Scott (2003) notes that much of scientific discourse from the same period “was composed largely of individual case studies that sought to extract specific details concerning the aetiology of male prostitution and the identity of the male prostitute” in a way that “understood male prostitution in terms of sociopathology” (p. 186).

Midnight Cowboy

engages the subject of male prostitution similarly. By focusing on one specific sex worker, the film acts as a sort of case study, and through its use of flashbacks to childhood and adolescent trauma,

Midnight Cowboy

works to get at the etiological roots of male sex work. By using flashbacks to childhood trauma in moments of present trauma, the film creates a link that posits Joe Buck’s past traumas as the inciting events that determined his current occupation.

Like Joe Buck’s childhood and adolescence, homosexual sex (both in sex work and, more generally, in its characters’ lives) is a complex and difficult subject in

Midnight Cowboy

. Joe Buck comes to New York with the dream of becoming a male gigolo paid to have sex with women, but when times are tough and his career as a gigolo seems to be failing, he resorts to sex work for male clients. These encounters, which, in the words of Benshoff and Griffin (2006), are presented as “sick and pitiful” (p. 135), always end poorly for Joe. In his first homosexual encounter, Joe allows a young man to give him oral sex in the balcony of an old, run-down movie theater. The encounter ends in failure, as the boy has no money to pay Joe and Joe leaves empty handed. In his second homosexual encounter, Joe prepares to have sex with an older gentleman whom he “gratuitously beats … senseless” to get money to buy his friend a bus ticket (Benshoff & Griffin, 2006, p. 135). Joe does not appear to murder the client, who is speaking to his mother on the phone just before Joe beats him and, thus, is made to represent the “repressed homosexual,” but the brutality of this scene is unmatched by any other encounter in the film. In these moments, Joe is not the cocky young stallion he envisions himself to be when he is with older women. Instead, homosexual acts symbolize Joe’s descent into extreme poverty and desperation that escalate to his encounter with the older gay man, which is by far the most abject moment for Joe and the most difficult for the audience to watch.

Midnight Cowboy

. Joe Buck comes to New York with the dream of becoming a male gigolo paid to have sex with women, but when times are tough and his career as a gigolo seems to be failing, he resorts to sex work for male clients. These encounters, which, in the words of Benshoff and Griffin (2006), are presented as “sick and pitiful” (p. 135), always end poorly for Joe. In his first homosexual encounter, Joe allows a young man to give him oral sex in the balcony of an old, run-down movie theater. The encounter ends in failure, as the boy has no money to pay Joe and Joe leaves empty handed. In his second homosexual encounter, Joe prepares to have sex with an older gentleman whom he “gratuitously beats … senseless” to get money to buy his friend a bus ticket (Benshoff & Griffin, 2006, p. 135). Joe does not appear to murder the client, who is speaking to his mother on the phone just before Joe beats him and, thus, is made to represent the “repressed homosexual,” but the brutality of this scene is unmatched by any other encounter in the film. In these moments, Joe is not the cocky young stallion he envisions himself to be when he is with older women. Instead, homosexual acts symbolize Joe’s descent into extreme poverty and desperation that escalate to his encounter with the older gay man, which is by far the most abject moment for Joe and the most difficult for the audience to watch.

At the same time, however,

Midnight Cowboy

provides a story in which its characters’ homo-social bonds foster their most productive relationships. Joe’s relationship with Rizzo (Hoffman), although platonic, is the “only genuine expression of love in the entire film … signaling the queer dynamic at work in the construction of male identity and male relationships” (Benshoff & Griffin, 2006, p. 135). As Joe travels to Florida with Rizzo at the end of the film, it is their relationship and Joe’s abandonment of his role as a sex worker that provide the hope for Joe’s future. In these moments, the film hints at a more complex understanding that breaks down the boundaries between homo-sociality and homosexuality but ultimately differentiates between homo-love and homo-sex—a sentiment that a

Los Angeles Times

preview article for

Midnight Cowboy

echoes, stating that the film exhibits a “tender story of a profound but not homosexual relationship” (Thomas, 1969, p. R22). Homo-sex (defined in Joe’s two homosexual hustling encounters) symbolizes abjection at its worst, while homo-love (defined by Joe’s relationship with Rizzo) provides an image of love at its purest; the boundaries are strictly maintained.

Midnight Cowboy

provides a story in which its characters’ homo-social bonds foster their most productive relationships. Joe’s relationship with Rizzo (Hoffman), although platonic, is the “only genuine expression of love in the entire film … signaling the queer dynamic at work in the construction of male identity and male relationships” (Benshoff & Griffin, 2006, p. 135). As Joe travels to Florida with Rizzo at the end of the film, it is their relationship and Joe’s abandonment of his role as a sex worker that provide the hope for Joe’s future. In these moments, the film hints at a more complex understanding that breaks down the boundaries between homo-sociality and homosexuality but ultimately differentiates between homo-love and homo-sex—a sentiment that a

Los Angeles Times

preview article for

Midnight Cowboy

echoes, stating that the film exhibits a “tender story of a profound but not homosexual relationship” (Thomas, 1969, p. R22). Homo-sex (defined in Joe’s two homosexual hustling encounters) symbolizes abjection at its worst, while homo-love (defined by Joe’s relationship with Rizzo) provides an image of love at its purest; the boundaries are strictly maintained.

Perhaps the most direct articulation of George Scott’s notion of the homosexual hustler as sick, criminal, and perverse, in contrast to the heterosexual gigolo as rational, healthy, and virile, is Paul Schrader’s

American Gigolo

(1980). The film depicts a very rigid line between the homosexual sex worker and the gigolo, presenting its protagonist as the heterosexual stallion that

Midnight Cowboy

’s Joe Buck so desperately wants to be; a connection that

Chicago Metro Times

reviewer Rocsan Richmond (1980) makes perfectly clear when, in her review of

American Gigolo

, she writes, “I’d looked forward to seeing ‘American Gigolo’ ever since I’d learned of its subject matter a year ago … I was hoping [Richard Gere] might take over where Jon Voight left off in ‘Midnight Cowboy’” (p. 10). Julian (Richard Gere) is positioned in direct opposition to Leon (Bill Duke), the film’s antagonist, a homosexual pimp, which led to allegations that the film was homophobic (Mass, 1990, p. 4). For Julian (much like Joe Buck), homosexual sex work was a necessity at a certain point in his career but was never intended to be the end goal. While

Midnight Cowboy

shows its audience the desperation that leads Joe to take on homosexual sex work,

American Gigolo

provides the backstory that posits Julian as an ex-hustler who is now a successful gigolo.

American Gigolo

positions homosexual sex work as the bottom rung on the ladder one must climb to become a successful gigolo—a rung to which Julian never wants to return. He repeats time and again that he absolutely will not do that “fag” or “kinky stuff.” Julian has graduated from the world of the abject (gay/dirty/bad/kinky) into the world of the vanilla (heterosexual/clean/good/as close to heteronormative as possible).

American Gigolo

(1980). The film depicts a very rigid line between the homosexual sex worker and the gigolo, presenting its protagonist as the heterosexual stallion that

Midnight Cowboy

’s Joe Buck so desperately wants to be; a connection that

Chicago Metro Times

reviewer Rocsan Richmond (1980) makes perfectly clear when, in her review of

American Gigolo

, she writes, “I’d looked forward to seeing ‘American Gigolo’ ever since I’d learned of its subject matter a year ago … I was hoping [Richard Gere] might take over where Jon Voight left off in ‘Midnight Cowboy’” (p. 10). Julian (Richard Gere) is positioned in direct opposition to Leon (Bill Duke), the film’s antagonist, a homosexual pimp, which led to allegations that the film was homophobic (Mass, 1990, p. 4). For Julian (much like Joe Buck), homosexual sex work was a necessity at a certain point in his career but was never intended to be the end goal. While

Midnight Cowboy

shows its audience the desperation that leads Joe to take on homosexual sex work,

American Gigolo

provides the backstory that posits Julian as an ex-hustler who is now a successful gigolo.

American Gigolo

positions homosexual sex work as the bottom rung on the ladder one must climb to become a successful gigolo—a rung to which Julian never wants to return. He repeats time and again that he absolutely will not do that “fag” or “kinky stuff.” Julian has graduated from the world of the abject (gay/dirty/bad/kinky) into the world of the vanilla (heterosexual/clean/good/as close to heteronormative as possible).

New Queer Cinema: Renegotiating “Male Hustlers”

It was these notions of homosexuality as abject and of homosexuals as “repressed, lonely fuck-ups and/or killers” that gay filmmakers working during the 1970s and early 1980s were trying to combat. However, one of the main tenets of the gay rights movement was, as Glyn Davis (2002) puts it, “assimilationist,” in that the movement was interested in positive representations of gay characters that said “we are just like you, really, so please accept us” (p. 25). It follows, then, that gay activists would not be interested in (re)claiming the image of the male sex worker since he, by his very definition, is opposed to the homonormative idea that “we are just like you” (“you” being the imagined heteronormative ideal). In direct opposition to notions of heternormativity, New Queer Cinema (NQC for short) emerged on the film festival scene in the early 1990s. These films offered, according to B. Ruby Rich (2004), “something new, renegotiating subjectivities, annexing whole genres, revising histories in their image” (pp. 15-16). These films exhibit a trait that Rich calls “‘Homo-Pomo’: there are traces … of appropriation and pastiche, irony, as well as a reworking of history with social constructionism very much in mind,” which makes them “ultimately full of pleasure” (pp. 15-16).

Other books

Blackmail (Restless Motorcycle Club Romance) by Julia Marie

The Prince's Scandalous Baby by Holly Rayner

Paying the Price by Julia P. Lynde

THE TEXAS WILDCATTER'S BABY by CATHY GILLEN THACKER,

OV: The Original Vampire (Book #1) by Christian, Erik

The Tory Widow by Christine Blevins

In Plain View by Olivia Newport

KissedByASEAL by Cat Johnson

No Use By Date For Love by Rachel Clark