Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks (19 page)

Read Maphead: Charting the Wide, Weird World of Geography Wonks Online

Authors: Ken Jennings

Tags: #General, #Social Science, #Technology & Engineering, #Reference, #Atlases, #Cartography, #Human Geography, #Atlases & Gazetteers, #Trivia

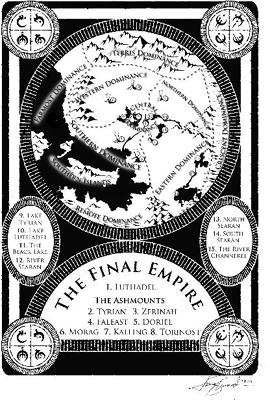

In fact, maps are so important to Brandon that he’s paid nine thousand dollars out of pocket to illustrate the book with full-page maps and other “ephemera.” Fantasy fans don’t just want maps that look as though they’ve been laid out digitally on a Mac. They want their maps to be artifacts

from the other world,

maintaining the illusion that it actually exists somewhere. The map in the front of

The Hobbit

wasn’t commissioned by a New York publisher; no, it’s the very same map the dwarves in the story use to find their way to the dragon’s lair. If you’re not inclined to believe in dwarves or dragons or their lairs, then burnt edges and water stains on the map can help suspend that disbelief.

Isaac Stewart is the local artist who produces Brandon’s maps, and it’s no easy job. He’s not just producing a nine-page atlas of territory that doesn’t exist. He’s producing, in effect, a sample page from each of nine vastly

different

atlases from nine different time periods. One map might be a street plan reminiscent of Regency London; the next might be a crude battle plan scraped on the back of a fictional crustacean called a “cremling.” Like real maps from the Age of Discovery,

some are meant to have been drawn by surveyors who actually saw the territory; others aren’t.

*

“

The achievement of

a plausible state is not so easy as it might appear,” wrote Gelett Burgess in 1902. Burgess was a humorist best remembered today for coining the word “blurb” and writing the poem “The Purple Cow,” but he was also an inveterate map geek. “There is nothing so difficult as to create, out of hand, an interesting coast line. Try and invent an irregular shore that shall be convincing, and you will see how much more cleverly Nature works than you.”

A video-game designer who moonlights as a fantasy mapmaker, Isaac probably has as much experience testing Burgess’s dictum as anyone in the world. A century later, coastlines are still hard. “You wind up doing this seizure thing with your hand, and it doesn’t work sometimes,” he tells me. Burgess’s solution was to spill water on his paper, pound it with his fist, and trace the resulting blotch. Isaac has developed his own tricks of the trade.

“It’s funny where I see maps now that I’m looking for them,” he says, pulling out his camera phone to show me his library of “found cartography.” “Ceiling textures. Clouds. Concrete spills in a road, those are good. They flow out in a way you might not expect.” A photo of a rust stain on a wall became an island in Brandon’s

Mistborn

series. An aerial view of a vast continent turns out to be a worn spot on a folding chair in a church basement. One picture looks remarkably like the Mediterranean, with verdant green hills and peninsulas surrounding a deep blue sea. It turns out to be guacamole stuck to the lid of a plastic tub. In my mind’s eye, I can picture Isaac at his kitchen counter, staring dumbfounded at his miniature discovery—like Balboa seeing the Pacific for the first time on that peak in Darien

*

—and then running for his camera. “Honey, don’t put that back in the fridge!

Don’t put it back in the fridge!

”

The Southern Islands of the Final Empire . . . and the rust stain that inspired them

Not every fantasy author feels as strongly about maps as Brandon does. Terry Pratchett includes a map page in every paperback of his popular

Discworld

series of comedy fantasy novels, but the map is always blank. A caption reads, “There are no maps. You can’t map a sense of humor.” It’s true that maps and texts make strange bedfellows sometimes. A map’s goal, after all, is to suggest stability and completeness,

while literature is all about suggestion, nuance,

not

showing everything.

But that tension hasn’t stopped some of my favorite writers from doodling maps of their imaginary settings—and not just in the fantasy ghetto, I’m talking books

without

half-naked barbarian chicks on the cover here. William Faulkner drew his own maps of Yoknapatawpha County; Thomas Hardy sketched Wessex. Even writers who ostensibly create their worlds as philosophical exercises become inordinately fascinated with jots and tittles of cartography. Thomas More’s

Utopia

describes the title island in such detail that he’s clearly a closet world-building geek, the only canonized Catholic saint I can think of who was so inclined. The first edition even included an addendum on Utopia’s alphabet and, of course, a detailed map. Yes, an appendix

and

a map! Epic fantasy readers would be over the moon.

I wonder aloud to Brandon and Isaac if fantasy readers crave immersion as a form of escape because they’re dissatisfied in some way with real life. I guess I’ve wandered a little too close to suggesting that fantasy nerds are all hopeless misfits, and Brandon calls me on it. “Look, I love my life, and I love fantasy. I have no reason to escape my world, but I still like going someplace new. Do people who like to travel hate where they live? When you open a fantasy book and see a map filled with new places, it makes you want to go explore them.”

On the flight home from visiting Brandon in Utah, I stare out the window at the Columbia Basin passing slowly beneath me. As the Cascade foothills loom ahead, I see huge trapezoidal holes in the greenery: what looks like virgin forest from the highway is, from the sky, exposed as a patchwork of ugly clear-cuts. I think about what Brandon said about fantasy readers as explorers. Jonathan Swift and Thomas More included maps in their books centuries ago, but fantastic maps didn’t really catch on as fetish objects until Tolkien’s time, less than a century ago, just as the time of global exploration was wrapping up. The Northwest Passage and the South Pole had fallen by the time

The Hobbit

was released, and Hillary scaled Everest the same year Tolkien drew the maps for

The Fellowship of the Ring

. There were, effectively, no blank

spaces left on the map. Maps of the Arctic tundra or Darkest Africa didn’t cut it for young adventurers anymore; they had to look elsewhere for new blank spaces to dream about. And so they found Middle-earth, Prydain, Cimmeria, Earthsea, Shannara.

If nothing else, talking to mappers of imaginary worlds has taught me that there’s a greater pleasure in maps than mere wayfinding. Austin Tappan Wright never needed to hike his way across Islandia in real life, but that didn’t stop him—or his readers—from developing a fanatical devotion to maps of the place. If you never open a map until you’re lost, you’re missing out on all the fun. As Robert Harbison once wrote, “

Nothing seems crasser

to a lover of maps than being interested in them only when you travel, like saving poetry for bus rides.”

Five or six hundred years ago, there

was

no clear distinction between fantasy maps and “real” ones. As I learned at the antique map fair, medieval mappaemundi regularly depicted fantastic places right alongside real ones: the land of Gog and Magog, from the Book of Revelation, was over by the Caspian Sea somewhere, often surrounded by the wall that, according to legend, Alexander the Great had built to imprison them. The Golden Fleece was drawn near the Black Sea, Noah’s ark was in Turkey, and Lot’s wife was shown still standing alongside the Dead Sea (as a pillar of salt, of course—you’d think she would have dissolved by now). Paradise was always off to the east somewhere, just over the horizon, surrounded by a ring of fire but still firmly rooted on solid ground.

*

These maps were expressions of religious devotion, not navigational aids.

Have things really changed that much today? When I browse through an atlas, I’m seeing page after page of places that I’ve visited exactly as often as I’ve visited Middle-earth or Narnia: never. Peru, Morocco, Tasmania. Even a road map of my hometown will show me streets that I’ve never driven, parks I’ve never visited. I can imagine those places from the map, but that’s all it is: my imagination. All maps are fantasy maps, in a way.

A flight attendant announces our descent into Seattle. As the plane dips through a layer of high clouds and the islands of Puget Sound come into view, I find it the easiest thing in the world to imagine these mountains and trees rendered in Tolkien’s spidery hand on faded parchment. Or as fractal patches of guacamole on an impossibly blue Tupperware sea.

Chapter 7

RECKONING

n

n

.:

calculation of one’s geographic position

Look, the world tempts our eye,

And we would know it all!

We map the starry sky,

We mine this earthen ball.

—MATTHEW ARNOLD

H

er name is Lilly Gaskin, and she knows where Turkmenigland” will not bestan and Bolivia and Ghana are. She can point out all these countries, as well as 130 others, on her wall map of the world, which probably puts her in the top 99.99th percentile of Americans. But don’t let Lilly’s geographical acumen give you an inferiority complex; there are probably plenty of things you can do that she can’t. Like read a book or pee on the potty chair. Lilly is just twenty-one months old.

Lilly’s eight-minute home video has been watched more than five million times since it was posted on YouTube in 2007. She’s the pigtailed cutie with big brown eyes who bounces on a crib mattress while stabbing her index finger confidently at forty-eight different countries named by her offscreen parents, taking occasional breaks to dance and clap for herself.

“Where’s Mexico?” her mom asks.

“May-hee-coh!” she squeaks happily

en español,

toddling over to the left side of the map to find it.

She’s adorable—cuter than the concentrated extract of a thousand baby koalas, so cute that

Ziggy

and

Family Circus

cartoons spontaneously burst into flame at her mere presence. The wildfire spread of Lilly’s Internet video led to appearances on

20/20, Rachael Ray,

and

Oprah

. She was a star before even graduating from diapers to pull-ups.

The more suspicious-minded will be asking two questions after seeing Lilly in action. First, what’s the trick? And second, what kind of horrific stage parents do this to their little girl?

“We had nothing to do with maps before Lilly did,” insists James Gaskin. I’ve tracked Lilly’s family down to Cleveland, Ohio, where her dad is currently working on his PhD in management and information science. Via Skype, I can see the whole family in their living room. Lilly is now four, and she’s clambering on the back and arms of the sofa with one of her younger sisters. James and Nikki, their parents, are a young, freshly scrubbed couple straight out of a Clearasil ad or a megachurch youth ministry.