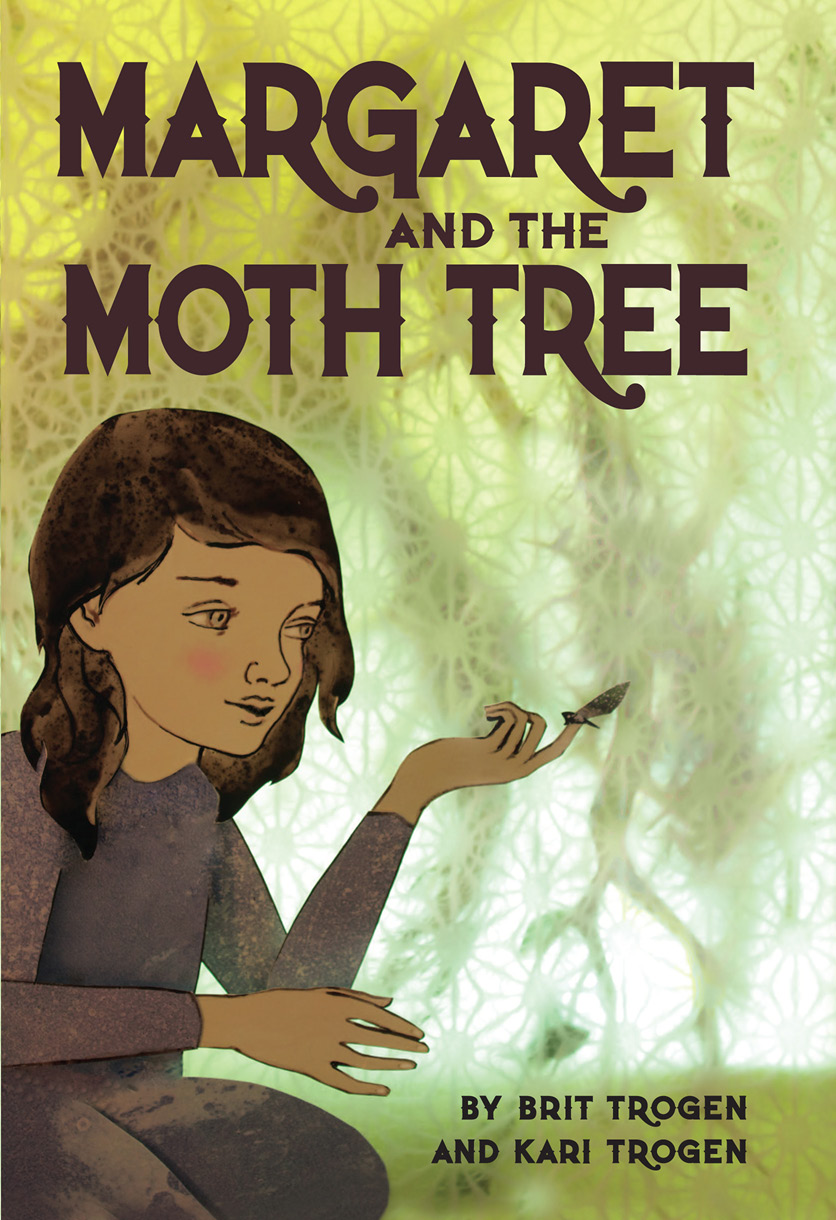

Margaret and the Moth Tree

Text © 2012 Brit Trogen and Kari Trogen

ISBN 978-1-55453-993-2 (ePub)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of Kids Can Press Ltd. or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright license, visit

www.accesscopyright.ca

or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

This is a work of fiction and any resemblance of characters to persons living or dead is purely coincidental.

Kids Can Press acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Ontario, through the Ontario Media Development Corporation's Ontario Book Initiative; the Ontario Arts Council; the Canada Council for the Arts; and the Government of Canada, through the BPIDP, for our publishing activity.

Published in Canada by

Kids Can Press Ltd.

25 Dockside Drive

Toronto, ON M5A 0B5

Published in the U.S. by

Kids Can Press Ltd.

2250 Military Road

Tonawanda, NY 14150

Edited by Sheila Barry

Designed by Marie Bartholomew

Cover illustration by Elly MacKay

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Trogen, Brit

Margaret and the moth tree / written by Brit Trogen and Kari Trogen.

ISBN 978-1-55453-823-2

I. Trogen, Kari II. Title.

PS8639.R64M37 2012Â Â Â Â Â jC813'.6Â Â Â Â Â C2011-905933-9

Contents

Chapter 7: The Home of the Dregs

Chapter 8: The Truth about Bullies

Chapter 9: Teaspoons and Treachery

Chapter 11: Nothing Worse Than a Thief

Chapter 12: The Dreg Who Didn't Exist

Chapter 16: The Truth about Moths

Chapter 23: Troubles Great and Troubles Small

Chapter 24: A Very Important Visit

Chapter 26: The Derangement of Toby Bobbins

Chapter 27: The Waking of the Moths

Chapter 28: The Rallying of the Dregs

For Janet, who raised us on books,

and our grandma, Vera, who loved to write

â B.T. and K.T.

PART ONE

THE FOUNDLING

CHAPTER 1

The Sad House

If this were a proper world, beautiful faces would belong to beautiful people.

Good people with kind hearts and clever minds would always have bright eyes and dazzling smiles, and bad people would have scraggly hair and warty noses. That way if you saw one of

them

coming, you could cross to the other side of the street and avoid them altogether.

But this is not a proper world. In our world, many bad people look quite nice, and many good people are not beautiful at all. Many good people aren't pretty or cute or even interesting-looking.

A very small girl named Margaret Grey was one of these.

“I don't want her,” said a woman with thick spectacles and white hair pinned up in a bun.

“I don't want her either,” said a man with dirty fingernails.

The reason Margaret was so small was that she was a toddler, though as toddlers go, she was not a very adorable one. She had

plain

brown hair and plain brown eyes and a plain little face that gave no hint that, even at one-and-a-half, she was both kindhearted and clever. She was the type of child most people would call

unremarkable

.

She was sitting on the floor of a very sad house. The man and the woman were staring down at her, and Margaret, who was holding a rattle, was staring back.

The house was called Grey Cottage and it had a large sign on its front door that said: FORECLOSED BY THE BANK. It was really quite a nice house, aside from the sign, and it hadn't always been a sad place. Until recently it had belonged to a couple called Anthony and Lillian Grey, and until recently this couple had been Margaret's parents.

Anthony and Lillian Grey were the type of parents you might wish for when your own are acting unreasonable. They took Margaret to the petting zoo and put on shadow puppet shows and made up stories with funny voices.

But here is where the sadness comes in. Anthony and Lillian Grey had recently perished in a freak car accident.

Grey Cottage no longer belonged to anyone. Two burly men were carrying bookcases and potted plants out its front door. And young Margaret was looking from one strange grown-up to the other, wondering which of them was going to take care of her.

“You'll have to take her,” said the woman, who was called Great-aunt Linda.

“I'm unfamiliar with toddlers,” said the man, who was called Cousin Amos.

“Don't talk back to me. I'm old, and old people must be humored,” said the woman, meaning that sometimes you have to do what old people tell you to keep them from getting snippy.

It is true that old people must be humored, just as it is true that small toddlers must be housed somewhere. So the grumbling man called Amos took Margaret by the hand, and that was that.

CHAPTER 2

A Lack of Greys

If you are very lucky and have had a more-or-less enjoyable life, you may not know much about lack.

Lack is a way of saying that you're missing something important. Margaret, for example, lacked parents, which meant she had to live with Cousin Amos. And Cousin Amos lacked a great many things.

He lived in a creaky old house covered in peeling paint, with a garden full of prickly weeds. His house lacked many of the things that toddlers need, like cuddly teddy bears and childproof corners and personal hygiene.

Amos was a lifelong bachelor, which meant he never cooked or cleaned at all if he could avoid it. His kitchen was foul, his bathroom was even worse, and he hadn't washed his socks in three years.

But the thing that was most lacking in Cousin Amos's house was conversation. Amos dreaded talking, and he never spoke to anyone unless he absolutely had to. Even then, he would limit himself to talking about vegetables or economics, because years of experience had taught him that these topics were guaranteed to put a stop to any conversation and allow him to return to his favorite habit of not talking.

So when Amos became Margaret's guardian, her small vocabulary of the words “dada,” “moose” and “eggplant” became completely unnecessary.

Instead of saying, “Please pass the brussels sprouts” at meal times, Amos would point and grunt.

Instead of saying, “Good night, Margaret. Don't let the bedbugs bite” at bedtime, Amos would pat her twice on the head and turn off the lights.

And instead of saying, “I'm so sorry about your parents. Is there anything I can do to make you feel better?” Amos didn't think to say anything at all.

When you spend a lot of time in a perfectly quiet house surrounded by perfectly quiet people, you have little choice but to be very quiet yourself. This is just what happened to Margaret Grey.

Without any brothers or sisters or playmates to shout and scream and holler with, Margaret didn't do the shouting and screaming and hollering that most children do. When she talked with the milkman on the step each morning, he could never stay long before continuing on his way. When she whispered to the German nanny over breakfast, the most she ever got in return was a nod or a close-lipped smile. And as soon as Margaret seemed old enough to look after herself, Amos got rid of the nanny altogether, and Margaret's world grew quieter still.

The life of a quiet girl in a quiet house may not seem a very remarkable thing. But Margaret learned something in Amos's house that very few people know how to do: Margaret learned how to listen.

You probably think that you know how to listen and, in a way, you are right. You know how to listen to the radio, or to someone singing in the shower. But Margaret's kind of listening was not the usual kind. Margaret learned how to

really truly

listen, which is something that very few people ever come to do.

By the time she was four years old, Margaret could hear things that even excellent listeners have trouble detecting, like a barn owl swooping through the air and the sound of the neighbor's cat yawning.

At four and a half, she could hear leaves falling in the yard and a mouse behind the wall chewing a bit of cheese.

And by the age of five, she could hear things that only a few people in the world have ever heard, like a shadowcreeping across the floorboards, and the first rays of sunlight as they passed through the window.

It is entirely possible that with a few more years of practice, Margaret could even have learned to listen to the very deepest and most secret thoughts that dance through people's minds.

But this is not what happened. Because shortly after Margaret's fifth birthday, when Cousin Amos died suddenly of antisanitosis, Margaret went to live with Great-aunt Linda. And from that point on, her life became very different.

“I never thought I'd have to spend my golden years looking after a child,” Great-aunt Linda said the first time she shooed Margaret through her door. “Life is full of surprises.”

“I'm sorry, Auntie,” said Margaret.

Great-aunt Linda was an old maid, which is exactly the opposite of a lifelong bachelor. Her house was spick and span, with fancy pillows on every chair and lacy tablecloths on every table and half a dozen hypoallergenic cats. And unlike Cousin Amos, who said hardly anything at all, Great-aunt Linda liked the sound of her own voice. She was especially fond of neat little phrases that don't really mean anything, like “life is full of surprises.”

“Idle hands are the devil's playthings,” she said on the morning of Margaret's arrival, handing her a piece of embroidery.

“Too many cooks spoil the broth,” she said on her way to play backgammon, shooing Margaret into the kitchen to make soup.

“Children should be seen and not heard,” she said when Margaret opened her mouth to say that she'd never made soup.

And so it was that instead of a house filled with quiet, Margaret found herself in a house filled with the mews of six hairless cats and the endless chattering of her great-aunt.

Great aunt Linda taught Margaret to read using passages from her favorite etiquette books, and gave her weekly quizzes on topics like “The Art of Polite Conversation” and “Forks and Their Uses.” As a reward for perfect marks, Margaret was taken to backgammon night, where other old ladies gave her butter tarts in the corner of a stuffy room.

As time went by, Margaret grew into a very polite little girl, but the marvelous listening skills that she'd had in Amos's house became rusty.

When she tried to listen for the first rays of sunlight, all she could hear was the mewing of cats.

When she tried to listen to the falling autumn leaves, they were drowned out by Great-aunt Linda's favorite radio drama.

And she soon stopped listening altogether.