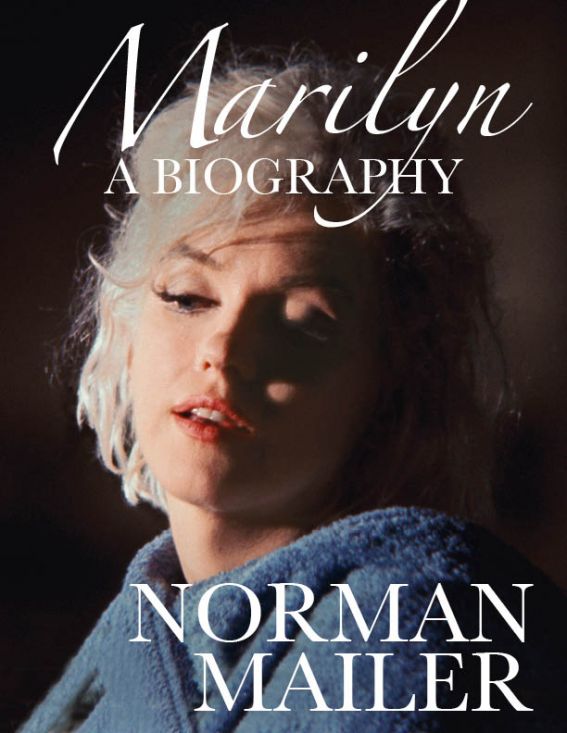

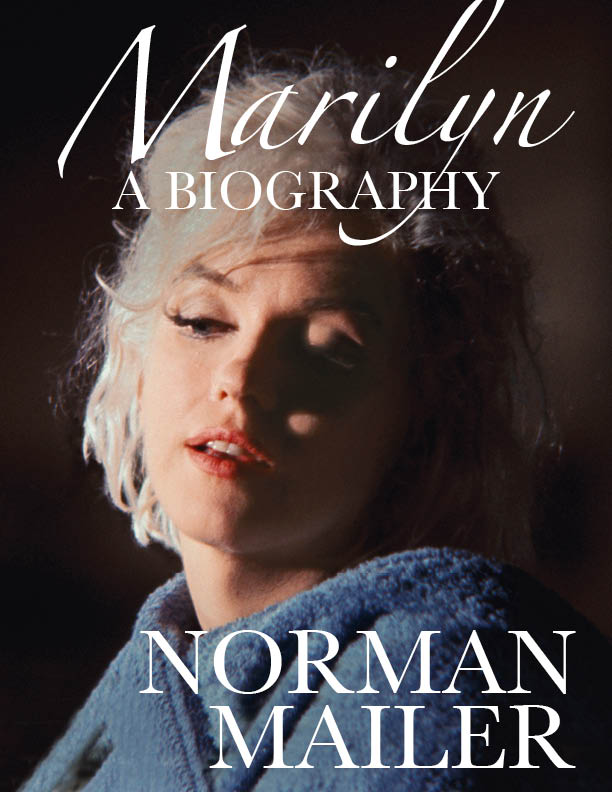

Marilyn: A Biography

Read Marilyn: A Biography Online

Authors: Norman Mailer

Tags: #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #marilyn monroe

by Norman Mailer

Published at Smashwords

Published by Polaris Communications, Inc.

Original Copyright © 1973 by Alskog, Inc.

& Norman Mailer

Electronic Version, Copyright © 2011 by

Polaris Communications, Inc.

And The Norman Mailer Estate

II Buried Alive

III Norma Jean

IV Snively, Schenck, Karger, and Hyde

V Marilyn

VI Ms Monroe

VII The Jewish Princess

VIII Lonely Lady

A Novel Biography

So we think of Marilyn who was every Man’s

love affair with America, Marilyn Monroe who was blonde and

beautiful and had a sweet little rinky-dink of a voice and all the

cleanliness of all the clean American backyards. She was our angel,

the sweet angel of sex, and the sugar of sex came up from her like

a resonance of sound in the clearest grain of a violin. Across five

continents the men who knew the most about love would covet her,

and the classical pimples of the adolescent working his first gas

pump would also pump for her, since Marilyn was deliverance, a very

Stradivarius of sex, so gorgeous, forgiving, humorous, compliant

and tender that even the most mediocre musician would relax his

lack of art in the dissolving magic of her violin. “Divine love

always has met and always will meet every human need,” was the

sentiment she offered from the works of Mary Baker Eddy as “my

prayer for you always” (to the man who may have been her first

illicit lover), and if we change

love

to

sex,

we have

the subtext in the promise. “Marilyn Monroe’s sex,” said the smile

of the young star, “will meet every human need.” She gave the

feeling that if you made love to her, why then how could you not

move more easily into sweets and the purchase of the full promise

of future sweets, move into tender heavens where your flesh would

be restored. She could ask no price. She was not the dark contract

of those passionate brunette depths that speak of blood, vows taken

for life, and the furies of vengeance if you are untrue to the

depth of passion, no, Marilyn suggested sex might be difficult and

dangerous with others, but ice cream with her. If your taste

combined with her taste, how nice, how sweet would be that tender

dream of flesh there to share.

In her early career, in the time of

Asphalt Jungle

when the sexual immanence of her face came up

on the screen like a sweet peach bursting before one’s eyes, she

looked then like a new love ready and waiting between the sheets in

the unexpected clean breath of a rare sexy morning, looked like

she’d stepped fully clothed out of a chocolate box for Valentine’s

Day, so desirable as to fulfill each of the letters in that

favorite word of the publicity flack,

curvaceous

, so

curvaceous and yet without menace as to turn one’s fingertips into

ten happy prowlers. Sex was, yes, ice cream to her. “Take me,” said

her smile. “I’m easy. I’m happy. I’m an angel of sex, you bet.”

What a jolt to the dream life of the nation

that the angel died of an overdose. Whether calculated suicide by

barbiturates or accidental suicide by losing count of how many

barbiturates she had already taken, or an end even more sinister,

no one was able to say. Her death was covered over with ambiguity

even as Hemingway’s was exploded into horror, and as the deaths and

spiritual disasters of the decade of the Sixties came one by one to

American Kings and Queens, as Jack Kennedy was killed, and Bobby,

and Martin Luther King, as Jackie Kennedy married Aristotle Onassis

and Teddy Kennedy went off the bridge at Chappaquiddick, so the

decade that began with Hemingway as the monarch of American arts

ended with Andy Warhol as its regent, and the ghost of Marilyn’s

death gave a lavender edge to that dramatic American design of the

Sixties which seemed in retrospect to have done nothing so much as

to bring Richard Nixon to the threshold of imperial power. “Romance

is a nonsense bet,” said the jolt in the electric shock, and so

began that long decade of the Sixties which ended with television

living like an inchworm on the aesthetic gut of the drug-deadened

American belly.

In what a light does that leave the last

angel of the cinema! She was never for TV. She preferred a theatre

and those hundreds of bodies in the dark, those wandering lights on

the screen when the luminous life of her face grew ten feet tall.

It was possible she knew better than anyone that she was the last

of the myths to thrive in the long evening of the American dream —

she had been born, after all, in the year Valentino died, and his

footprints in the forecourt at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre were the

only ones that fit her feet. She was one of the last of cinema’s

aristocrats and may not have wanted to be examined, then

ingested

, in the neighborly reductive dimensions of

America’s living room. No, she belonged to the occult church of the

film, and the last covens of Hollywood. She might be as modest in

her voice and as soft in her flesh as the girl next door, but she

was nonetheless larger than life up on the screen. Even down in the

Eisenhower shank of the early Fifties she was already promising

that a time was coming when sex would be easy and sweet, democratic

provender for all. Her stomach, untrammeled by girdles or sheaths,

popped forward in a full woman’s belly, inelegant as hell, an

avowal of a womb fairly salivating in seed — that belly which was

never to have a child — and her breasts popped buds and burgeons of

flesh over many a questing sweating moviegoer’s face. She was a

cornucopia. She excited dreams of honey for the horn.

Yet she was more. She was a presence. She was

ambiguous. She was the angel of sex, and the angel was in her

detachment. For she was separated from what she offered. “None but

Marilyn Monroe,” wrote Diana Trilling,

could suggest such a purity of sexual

delight: The boldness with which she could parade herself and yet

never be gross, her sexual flamboyance and bravado which yet

breathed an air of mystery and even reticence, her voice which

carried such ripe overtones of erotic excitement and yet was the

voice of a shy child — these complications were integral to her

gift. And they described a young woman trapped in some never-never

land of unawareness.

Or is it that behind the gift is the tender

wistful hint of another mood? For she also seems to say, “When an

absurd presence is perfect, some little god must have made it.” At

its best, the echo of her small and perfect creation reached to the

horizon of our mind. We heard her speak in that tiny tinkly voice

so much like a little dinner bell, and it tolled when she was dead

across all that decade of the Sixties she had helped to create,

across its promise, its excitement, its ghosts and its center of

tragedy.

Since she was also a movie star of the most

stubborn secretiveness and flamboyant candor, most conflicting

arrogance and on-rushing inferiority; great populist of

philosophers — she loved the working man — and most tyrannical of

mates, a queen of a castrator who was ready to weep for a dying

minnow; a lover of books who did not read, and a proud, inviolate

artist who could haunch over to publicity when the heat was upon

her faster than a whore could lust over a hot buck; a female spurt

of wit and sensitive energy who could hang like a sloth for days in

a muddy-mooded coma; a child-girl, yet an actress to loose a riot

by dropping her glove at a premiere; a fountain of charm and a

dreary bore; an ambulating cyclone of beauty when dressed to show,

a dank hunched-up drab at her worst — with a bad smell! — a giant

and an emotional pygmy; a lover of life and a cowardly hyena of

death who drenched herself in chemical stupors; a sexual oven whose

fire may rarely have been lit — she would go to bed with her

brassiere on — she was certainly more and less than the silver

witch of us all. In her ambition, so Faustian, and in her ignorance

of culture’s dimensions, in her liberation and her tyrannical

desires, her noble democratic longings intimately contradicted by

the widening pool of her narcissism (where every friend and slave

must bathe), we can see the magnified mirror of ourselves, our

exaggerated and now all but defeated generation, yes, she ran a

reconnaissance through the Fifties, and left a message for us in

her death, “Baby go boom.” Now she is the ghost of the Sixties. The

sorrow of her loss is in this passage her friend Norman Rosten

would write in

Marilyn – An Untold Story

:

She was proud of her dishwashing and held up

the glasses for inspection. She played badminton with a real flair,

occasionally banging someone on the head (no damage). She was just

herself, and herself was gay, noisy, giggling, tender. Seven

summers before her death….She liked her guest room; she’d say,

“Make it dark, and give me air.” She slept late, got her own

breakfast and went off for a walk in the woods with only the cat

for company.

Marilyn loved animals; she was drawn to all

living things. She would spend hundreds of dollars to try to save a

storm-damaged tree and would mourn its death. She welcomed birds,

providing tree houses and food for the many species that visited

her lawn, she worried about them in bad weather. She worried about

dogs and cats. She once had a dog that was by nature contemplative,

but she was convinced he was depressed. She did her best to make

him play, and that depressed him even more; on the rare occasions

when he did an antic pirouette, Marilyn would hug and kiss him,

delirious with joy.

They are loving lines. Rosten’s book must

offer the tenderest portrait available of Monroe, but those who

suspect such tender beauty can find other anecdotes in Maurice

Zolotow’s biography:

One evening, some of the cast – though not

Monroe – were watching the rushes of the yacht sequence. . . .

[Tony Curtis] is posing as a rich man’s son who suffers from a

frigid libido. Girls cannot excite him. Monroe decides to cure him

of his ailment by kissing him and making love to him. On the fifth

kiss, the treatment succeeds admirably.

In the darkness, someone said to Curtis, “You

seemed to enjoy kissing Marilyn.” And he said loudly, “It’s like

kissing Hitler.”

When the lights came on, Paula Strasberg was

crying. “How could you say a terrible thing like that, Tony?” she

said. “You try acting with her Paula,” he snapped, “and see how you

feel.”

During much of the shooting, Monroe was

reading

Paine’s Rights of Man

. One day, the second assistant

director, Hal Polaire, went to her dressing room. He knocked on the

door. He called out, “We’re ready for you, Miss Monroe.”

She replied with a simple obliterative. “Go

fuck yourself,” she said. Did she anticipate how a future

generation of women would evaluate the rights of men? Even so

consummate a wit as Billy Wilder would yet describe her as the

meanest woman in Hollywood, a remark of no spectacular humor that

was offered nonetheless in an interview four years after her death,

as though to suggest that even remembering Marilyn across the void

was still sufficiently irritating to strip his wit. Yet during the

filming of

Let’s Make Love

she was to write in her dressing

room notebook, “What am I afraid of? Why am I so afraid? Do I think

I can’t act? I know I can act but I am afraid. I am afraid and I

should not be and I must not be.” It is in fear and trembling that

she writes. In dread. Nothing less than some intimation of the

death of her soul may be in her fear. But then is it not hopeless

to comprehend her without some concept of a soul? One might

literally have to invent the idea of a soul in order to approach

her. “What am I afraid of?”