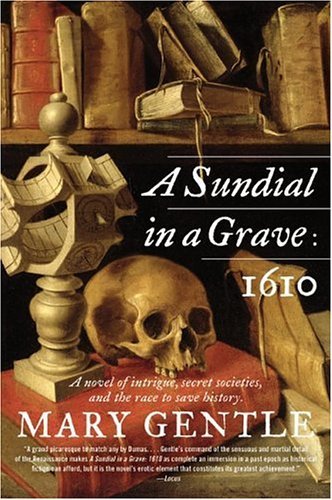

Mary Gentle

Authors: A Sundial in a Grave-1610

Mary Gentle

For Dean, my first reader;

without whom, nothing.

“[…] make

The sons of sword, and hazard fall before

The golden calf, and on their knees, whole nights, Commit idolatry with wine, and trumpets:”

II.i. 18–20,

The Alchemist,

Ben Jonson (1610)

Translator’s Foreword

Part 1

Cipher Journal of Robert Fludd

1

Rochefort, Memoirs

2

Rochefort, Memoirs

3

Rochefort, Memoirs

4

Rochefort, Memoirs

5

Rochefort, Memoirs

6

Rochefort, Memoirs

7

Rochefort, Memoirs

8

Rochefort, Memoirs

Part 2

Excerpt from the Report of the Samurai Tanaka Saburo to Shogun Tokugawa Hidetada:

9

Rochefort, Memoirs

10

Rochefort, Memoirs

11

Rochefort, Memoirs

12

Rochefort, Memoirs

13

Rochefort, Memoirs

14

Rochefort, Memoirs

15

Rochefort, Memoirs

16

Rochefort, Memoirs

17

Rochefort, Memoirs

18

Rochefort, Memoirs

19

Rochefort, Memoirs

20

Rochefort, Memoirs

21

Rochefort, Memoirs

Part 3

Untitled

22

Rochefort, Memoirs

23

Rochefort, Memoirs

24

Rochefort, Memoirs

25

Rochefort, Memoirs

26

Rochefort, Memoirs

27

Rochefort, Memoirs

28

Rochefort, Memoirs

29

Rochefort, Memoirs

30

Rochefort, Memoirs

31

Rochefort, Memoirs

32

Rochefort, Memoirs

Part 4

The Viper and Her Brood

33

Rochefort, Memoirs

34

Rochefort, Memoirs

35

Rochefort, Memoirs

36

Rochefort, Memoirs

37

Rochefort, Memoirs

38

Rochefort, Memoirs

39

Rochefort, Memoirs

Part 5

Excerpt from the Report of the Samurai Tanaka Saburo to Shogun Tokugawa Hidetada, Third Son of Great Tokugawa Ieyasu

40

Rochefort, Memoirs

41

Rochefort, Memoirs

42

Rochefort, Memoirs

43

Rochefort, Memoirs

44

Rochefort, Memoirs

45

Rochefort, Memoirs

46

Rochefort, Memoirs

47

Rochefort, Memoirs

48

Rochefort, Memoirs

49

Rochefort, Memoirs

50

Rochefort, Memoirs

51

Rochefort, Memoirs Untitled

Afterword—Author’s Note

Hic Jacet

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Cover

Copyright

I

t’s about sex, and cruelty, and forgiveness.

None of this is apparent from our previous knowledge of the story.

In 1687 the sole surviving manuscript of the

Memoirs

of Valentin Raoul Rochefort, French ex-gentleman and professional hired killer, was thrown on the fire by an outraged descendant.

Although the manuscript must have been rescued from the blaze soon afterward, many pages were found to be blackened and unreadable, and most of Rochefort’s words were lost to posterity. It’s only luck that we have a complete document—both the burned and the undamaged pages shoved carelessly together into a wooden box, by some anonymous rescuer, together with a few other minor documents of the time.

Now, after four hundred years, computer-assisted image enhancement can give us a version that is, 99 percent accurately, what Rochefort wrote.

In the middle of the nineteenth century a French novelist took what was legible of the

Memoirs

and made a popular and eminently readable novel out of it. I suppose that these days most of us know

Noblesse D’Épée

(or, as the English translator called it,

The Sons of Sword and Hazard

) from children’s editions, or from a movie version of the story. The bare facts are well known. The novel was written in

The Three Musketeers

. (Scandal later claimed that Maquet was indeed the sole and only author of many of Dumas’ novels—but it did him no good financially.) We know that Maquet had read a chapbook version of the

Memoirs

early on in his life; he recycled the names of the protagonists as minor characters in his synopses for Dumas.

Maquet ignored—because there was, then, no way of reading them—the oddest and most disquieting parts: the Rosicrucian conspiracy theories of the early seventeenth century, and a form of futurology that makes Nostradamus look an amateur.

The

Memoirs

themselves lapsed into obscurity. Ironically, when Maquet wrote

Noblesse D’Épée

, he had the frustrating experience of finding it dismissed as bad Dumas pastiche. This is perhaps why the novel never had a great success in

The Sons of Sword and Hazard

was an immediate success. Edward Rose adapted a version for the stage before the First World War, and a silent-movie version appeared not long after the war ended. Indeed, that first movie, made in black and white, starring Conrad Veidt as Rochefort, and Fritz Leiber Sr. as the Duc de Sully, was almost as great a success as the book version (which reached its twenty-first printing by 1906). Other movies followed through the twentieth century. The Richard Lester early 1970s remake is my personal favorite, since it has a good deal of the unbuttoned extravagance of the original, even if it does make hay with what we knew of the plot.

I should speak personally here. I have always loved

The Sons of Sword and Hazard

. I love Weyman’s book. I love all the lace-and-steel movie versions, up to the Leonardo DiCaprio vehicle it has most recently become. (Although a more unlikely Rochefort I cannot imagine. The Russell Crowe/Angelina Jolie version currently filming will, I think, be rather more true to the original.)

And in the Spring of 1986, I first discovered that the protagonist (it is awkward to call him the “hero”) of

The Sons of Sword and Hazard

was a real historical person.

It is possible that both Maquet and Weyman were not aware of this.

That’s not as incredible as it sounds. To take the obvious example, Alexandre Dumas clandestinely lifted the plot and characters of

The Three Musketeers

from the work of a late-seventeenth-century historical novelist, Gatien de Courtilz de Sandras. Dumas loved to claim historical reality for his D’Artagnan, Athos, Porthos, and Aramis—but it seems likely that he remained convinced that his characters were works of fiction. In fact, research now shows that (even if the novel’s plot owes more to gossip and rumor), there were at least historical musketeers in the King’s forces who went under those names: Charles de Batz-Castelmore, Sieur of Artagnan; Armand de Sillégue, Seigneur d’Athos et d’Auteville; Isaac de Portau; and Henri d’Aramitz.

The “novelist” Courtilz was, however inaccurately, a biographer.

Likewise I discovered

The Sons of Sword and Hazard

is history inadvertently presented as fiction. Rochefort—Valentin Raoul St Cyprian Anne-Marie Rochefort de Cossé Brissac, to give him his full name—is, at the very least, based on a real man.

That fact formed the seed of an obsession.

All of it was old news among literary critics, true; or among those few of them interested in the “sensation” adventure novel. The complete

Memoirs

existed only in their damaged form, and it was by pure accident that the fire-blackened pages were not thrown away. I managed a trip to Paris on a student’s grant, and saw the original manuscript; my schoolgirl French not helping me much with the (very kind) curators, nor with the crabbed Early Modern French of Rochefort’s spiky handwriting.

Ten years later, having managed to force a fair amount of that version of French into my brain—I’m notoriously bad at languages—I was on a second Masters degree which had nothing to do with post-medieval scholarship. However, it was at that university that I first discovered people using computer techniques both to analyze medieval and post-medieval handwriting, and to enhance images to uncover previously “lost” damaged texts.

I had had it in mind, before that, to translate a new edition of

The Sons of Sword and Hazard

; but that doesn’t seem necessary, given the freshness of both Weyman’s and Maquet’s writing. For those who expect

Prithee!

and

Gadzooks!

, this is always a pleasant surprise.

I knew instantly that I wanted to apply the new technology’s techniques to Rochefort’s

Memoirs

.

So, this translation of the

Memoirs

is an adjunct to the classic novel. I’ve tried to translate Rochefort’s recovered narrative into modern English, keeping a flavor of the original terms, but making it a story we can easily read.

I should perhaps warn the unwary new reader that the complete text of the

Memoirs

contains passages that are, to twenty-first-century eyes, erotic or pornographic, according to the reader’s definition. Rochefort, writing some forty years after Montaigne, follows the pattern of the

Essais

by his un-flinching confession of his own conflicted sexual life. If

The Sons of Sword and Hazard

is a story of Machiavellian politics and romance, the

Memoirs

are, among other things, the story of a sexual obsession.

But perhaps that is the same thing. Any reader of Stanley J. Weyman, Rafael Sabatini, Georgette Heyer, and Dumas must admit that the popular historical Romance has a powerful unacknowledged erotic subtext, from which it draws secret potency.

In some ways, that is also the answer to the question: why a new edition of the

Memoirs

now? I doubt it could have been published in 1894, even if it had been known. However, we don’t now face the censorship, or the self-censorship, of Victorian England. Rochefort’s confessions can perhaps be read with sympathy and understanding—if, also, with some amusement.

I should note here that the strangest parts of the

Memoirs

are invariably those that have the most fire damage—to the point where I suspect this can only be deliberate. Someone desired to burn the parts of Rochefort’s narrative that are to do with his sexual life. Someone also attempted to destroy almost all of what Rochefort wrote about the prognostications of the English physician and Rosicrucian theorist Robert Fludd (who barely appears in the novelizations). One can only speculate why.

Here, then, is the rediscovered and retranslated story, separated from us by one language and four centuries. The recovered

Memoirs

, rendered as fully as I can. Or perhaps it would be more reasonable to say: as adequately as Time permits.

And where it seems necessary—where they shed light on the writings of Valentin Raoul Rochefort—I have added to the history those other documents that were included in the wooden box that contains the manuscript of the

Memoirs

.

With one of which, we begin:

Mary Gentle

London,