Mary Tudor (15 page)

37. The racking of Cuthbert Simpson. The use of torture on the victims was unusual, but Simpson was the deacon of the London congregation, and he was racked (unsuccessfully) to make him reveal their names.

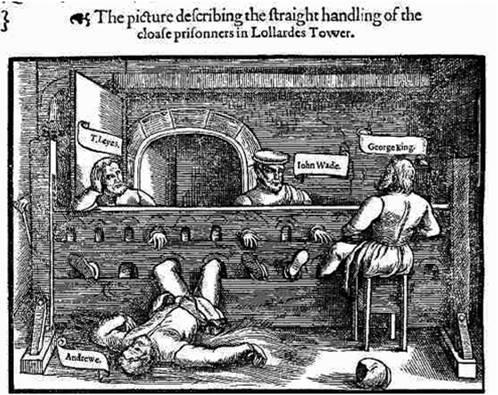

38. ‘Strait handling’ was more common, as this reconstruction of the ordeal of prisoners in the Lollards’ Tower at Lambeth makes plain.

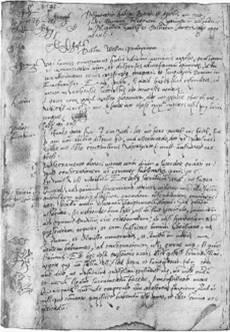

39. An account of the disputation held at Oxford in April 1554. This extract is from the exchanges between Hugh Latimer and Richard Smith, with Dr Weston as Prolocutor. It was from this manuscript that Foxe printed his version.

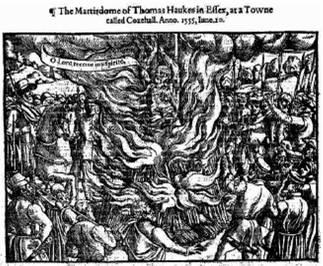

40. A lively depiction of the burning of Thomas Haukes in June 1555. Haukes was one of the few gentlemen to suffer during the persecution. Most Protestants of that status fled abroad.

41. One of the most appalling atrocities of the persecution was the burning of a pregnant Margaret Cauches on Guernsey. The hapless woman gave birth in the flames, and her infant perished as well. An enquiry was launched under Elizabeth, from which most of our knowledge of the incident is derived.

42. The burning of Thomas Tompkyns’ hand by Bishop Bonner. This example of Bonner’s alleged cruelty was a part of Foxe’s campaign against the bishop. Whether the incident actually occurred is uncertain.

43. Richmond Palace.

44. Calais and its harbour, from a sixteenth-century drawing. It was the loss of Rysbank (the tower in the middle of the picture) which sealed the fate of Calais during its capture by the French in January 1558.

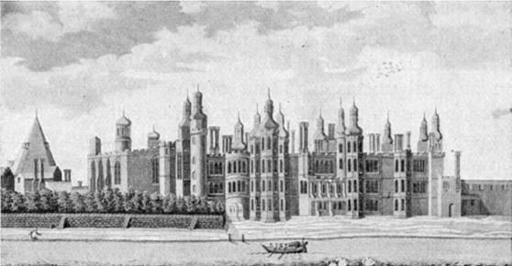

45. Hampton Court, acquired by Henry in 1525, and subsequently much rebuilt. Edward VI was born there in September 1537.

HENRY REARRANGES THE SUCCESSION, 1544

His Majestie therefore thinketh convenient afore his departure beyond the seas that it be enacted by his Highness with the assent of the lords spiritual and temporal and the commons in this present parliament assembled and by authority of the same, and therefore be it enacted by the authority aforesaid that in case it shall happen that the King’s Majesty and the said excellent Prince his yet only son Prince Edward and heir apparent to decease without heir or either of their bodies lawfully begotten (as God defend) so that there be no such heir male or female of any of their two bodies to have and inherit the said Imperial Crown and other his dominions according and in such manner and form as in the foresaid Act and now in this is declared. That then the said Imperial Crown and all other the premises shall be to the Lady Mary the King’s Highness daughter and to the heirs of the said Lady Mary lawfully begotten, with such condition as by his Highness shall be limited by his Letters Patent under his Great Seal or by his Majesty’s last will in writing signed with his gracious hand; and for default of such issue the said Crown Imperial and all other the premises shall be to the Lady Elizabeth the king’s second daughter and to the heirs of the said Lady Elizabeth lawfully begotten, with such conditions as by his Highness shall be limited by his Letters Patent under his Great Seal or by his Majesty’s last will in writing signed with his gracious hand. Anything in the said Act made in the said 28th year of our said Sovereign Lord to the contrary of this Act notwithstanding …

[Statute 35 Henry VIII, cap. 1.

Statutes of the Realm

, iii, p. 955.]

Mary’s role in all this was her marriage potential, and she was deployed as circumstances required, now to the Imperialists, now to the French; sometimes with her legitimacy negotiable, sometimes not.

[97]

The only one of these suitors whom she actually saw was Duke Philip of Bavaria, the son of the Elector Palatine. Philip was not an official candidate, and appears to have been acting on his own initiative. He arrived in England just before Christmas 1539, offering his military services to the King of England and asking for Mary’s hand in marriage. Either charmed by his knight-errantry or dazzled by his effrontery, Henry allowed a negotiation to take place. As this was a private venture, Cromwell immediately sent a message to Mary to ascertain her feelings. Philip was a Lutheran, and her response was that she would ‘prefer never to enter into that kind of religion’. Nevertheless, she would do as her father wished. On 26 December, while Mary was at court for Christmas, they met in the gardens of the Abbot of Westminster. The only account we have of their encounter comes from Marillac, the French ambassador, who must have got it from one of Mary’s attendants. The duke had actually ventured to kiss her! This must mean marriage, Marillac concluded, because he was no kin, and no English nobleman would have dared so to presume.

[98]

They conversed partly in Latin and partly in German (the latter through an interpreter), and as they parted he swore that he would make her his wife. Mary responded prosaically that she would do as her father should determine. It must have been a chilly tryst and was not, on her part, very romantic; but it was the nearest thing to real courtship that she was ever to experience. Marillac expected a marriage within weeks, and indeed a treaty was drawn up, whereby Philip would have accepted her as incapable of succession, and with a modest dowry, but it was never implemented. Henry probably decided that he could not afford to lose so useful a diplomatic instrument so easily, and within a month Philip had departed, a disappointed man.

He did not give up easily though. In the spring of 1540 he wrote to renew his suit, but his letter went astray in the confusion that preceded Cromwell’s fall, and he had to be satisfied with the Order of the Garter. He came to England again in May 1543, with the same military and matrimonial agenda, but he did not see Mary; he departed with a gift, but no other satisfaction. In March 1546 Philip did finally obtain a contract to supply 10,000 foot soldiers and 1,000 horsemen, and also another interview with Mary, although nothing is known about this encounter. Finally, in September of the same year he came in response to Henry’s initiative, and the old speculation of a marriage was immediately renewed. However, this time he was an emissary for his father, and the negotiation came to nothing.