MASQUES OF SATAN

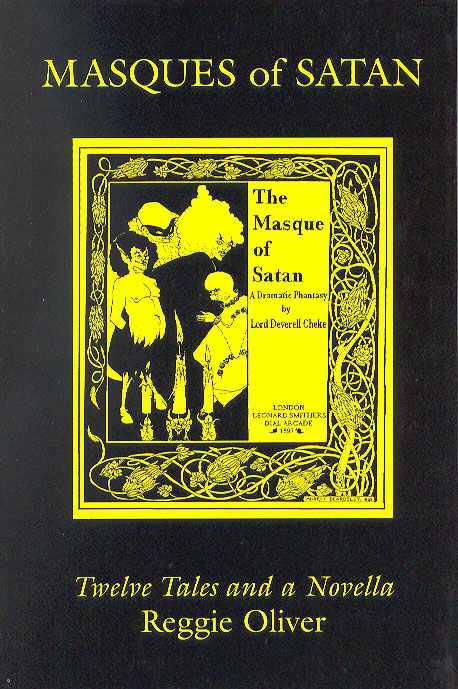

MASQUES of SATAN

Twelve Tales and a Novella

Reggie Oliver

MASQUES OF SATAN

ISBN: 9781553101468 (Kindle edition)

ISBN: 9781553101475 (ePub edition)

Published by Christopher Roden

For Ash-Tree Press

P.O. Box 1360, Ashcroft, British Columbia

Canada V0K 1A0

http://www.ash-tree.bc.ca/eBooks.htm

First electronic edition 2011

First Ash-Tree Press edition 2007

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictionally, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have any control over, and does not assume any responsibility for, third-party websites or their content.

Copyright © Reggie Oliver 2007, 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

Produced in Canada

CONTENTS

Shades of the Prison House,

a Novella

FOR MY NIECE

CAROLINE OLIVER

Read by a taper when the needling star

Burns red with menace in heaven’s midnight cope.

Walter de la Mare

MASQUES OF SATAN

Introductory

THE GHOST STORY is a very ancient and a very strange artefact. It purports to tell of disturbances in what we understand to be the natural order of things. This account of them is intended to induce fear, or to trouble the reader in some way. An explanation is offered for the alarming phenomena, but it is rarely a complete one, and the reader is meant to be left with an abiding sense of disquiet which is somehow, paradoxically, satisfying to the psyche.

Not long ago I was at a dinner party at which our host told a ‘true’ ghost story. As an undergraduate at Oxford, he was in his rooms one night with a friend when suddenly the curtains on his windows billowed out, as if from a blast of wind. He went to the windows to find that they were shut. They heard knocking at the door, but, on going to answer it my host found no one outside the door. Later that night he was in bed when he heard a crash coming from the sitting room of his set. He did not dare venture out of his bedroom, but the following morning he discovered that the mirror which hung above the mantelpiece had been smashed onto the ornaments upon it and then carefully replaced. These phenomena never occurred again and the only explanation was found in a college legend that an undergraduate had once committed suicide by somehow attaching one end of a rope to the fireplace of my host’s rooms, putting the other round his neck and launching himself down the steep flight of stairs from his set of rooms to the quad below.

Even if written up with skill, that would make a pretty poor fictional ghost story. The events are incoherent and not particularly chilling; the ‘explanation’ is vague, banal and unconvincing. All the same, I enjoyed listening to it because my host is an intelligent, unfanciful man and a completely credible witness. The story, for all its obvious shortcomings as a work of art, did offer two ingredients essential to any ghost story: alarm and mystery. It compensated for its artistic inadequacies by being true.

What the fictional ghost story has to add, to compensate in its turn for

not

being true, is a visionary element. Its events must somehow amount to an insight, however brief and baffling, into the metaphysical world. It must in some way transcend the normally impenetrable wall of death. Ever since human beings had speech and began to tell stories they have wanted some transcendental aspect to be part of the weave. What is interesting is that story tellers have rarely made that transcendence reassuring. Part of the perverse-seeming, but obviously normal, pleasure we derive from the ghost story is that far from comforting us, it shakes us up.

In about 2000 BC the first work of literature known to us and still extant was punched onto clay tablets. This was

The Epic of Gilgamesh

which was written in Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq. It tells of ghosts, and takes as its main theme one which is at the back of most if not all ghost stories. It was summed up by the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who called

Gilgamesh

‘

das Epos der Todesfurcht

’, an epic about the fear of death.

In one version of the epic the hero Gilgamesh’s friend Enkidu describes a dream in which he is dragged down to the land of the dead:

He bound my arms like the wings of a bird,

to lead me captive to the house of darkness, seat of Irkalla:

to the house which none who enters ever leaves,

on the path that allows no journey back,

to the house whose residents are deprived of light,

where soil is their sustenance and clay their food,

where they are clad like birds in coats of feathers,

and see no light; but dwell in darkness.

On door and bolt the dust lay thick,

on the House of Dust was poured a deathly quiet.

In the House of Dust that I entered . . .

That seems to me an admirable passage which I or any modern practitioner of horror would be proud to have written. It has a disturbing visionary strangeness — why are the dead ‘clad like birds in coats of feathers’, for instance? — and yet an authenticity. It seems to tell of something that has been genuinely felt and experienced by the anonymous 4000-year-old author.

There are several versions of the Gilgamesh epic. In the one quoted Enkidu dies, and Gilgamesh goes on a vain search for immortality as a result. In another version Enkidu goes, in spite of Gilgamesh’s warning, to the world of the dead and is trapped there. Gilgamesh tries to rescue him and obtains only a brief interview with Enkidu’s ghost. The news from the other side is not good.

Move on a millennium and we come to the earliest Greek Literature,

The Iliad

and

The Odyssey

, which are the mainsprings of so much classical and modern European literature. Ghosts play an important and dynamic role in both stories. In

The Iliad

the ghost of Patroclus appears to Achilles after he has killed Hector and urges him to give him a decent burial. This initiates the final movement of

The Iliad

, when Achilles goes to beg the body of Patroclus off Priam in Troy. The ghost is described as a spirit and an image (

eidolon

) but — oddly — ‘without wits’, even though Patroclus has just delivered a coherent speech to Achilles prophesying his friend’s death before the walls of Troy. Why? I can only explain it by suggesting that this Homeric idea of a talking, but essentially witless, ghost is a precursor of the idea held by some psychic researchers today that ghosts are psychic shells; in other words that human beings leave behind not only a physical corpse in the form of a dead body but a psychic one, too, and this can cause nuisance in the form of poltergeists and the like, or leave a sort of imprint on the place where it suffered a traumatic event. Visions of the afterlife are explored in

The Odyssey

, in the famous sequence known as the

Nekuia

when Odysseus visits the Underworld and holds conversations with the dead. This is a fascinating episode for a number of reasons, but one incident is especially worth mentioning because it disposes of the notion that human beings invented the afterlife as wish fulfilment, as a kind of consolation prize for the misery of this life. Nothing could be further from the truth. All early accounts of the afterlife — we’ve seen what

The Epic of Gilgamesh

has to say — are frankly pretty discouraging. There are no happy ghosts.

So in

The Odyssey

one of the ghosts that Odysseus interviews is that of Achilles, and he utters these famous lines:

‘I would rather be a serf, working on the land, even for a poor man, than a Prince among the dead.’ (I paraphrase slightly.)

In other words, I would rather be the lowest of the low among the living than dead. The speaker is the hero Achilles who dwells in the best part of the land of the dead, the Elysian Fields. For Homer there is no ‘pie in the sky’: that is a comparatively late addition in religious thinking.