Massacre in West Cork (15 page)

Read Massacre in West Cork Online

Authors: Barry Keane

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Ireland, #irish ira, #ireland in 1922, #protestant ireland, #what is the history of ireland, #1922 Ireland, #history of Ireland

This story has one other strand that has not been discussed in detail before. At the start of April 1922 the inhabitants of Killumney, less than one kilometre from the Hornibrook house, were shocked by the kidnap of Timothy C. Hurley by armed men early one morning. According to the

Southern Star

of 22 April, this was apparently a case of mistaken identity and was thought to be linked to a wages dispute between the farmers and the labourers in the area – the post-war recession had struck with a vengeance during the middle of 1921 and across County Cork labourers were striking, occupying farms and attempting to intimidate the farmers into maintaining wages at current levels. The Hornibrook farm had been damaged in early February, and it is possible that this damage was linked to this dispute. When Matilda and Edward Woods visited Ballygroman two weeks before the kidnapping, they took the most unusual step of recording a full inventory of the furniture and farm contents – the family must have been concerned about their property, at least in relation to theft or malicious damage. This inventory was submitted as evidence in a compensation claim before the circuit court in Cork in 1926. It is possible that Herbert Woods came to Ballygroman at this time as an extra insurance policy, although there is no evidence of this.

25

None of these incidents on their own amounts to very much, but when combined with the fact that the Hornibrooks could get few people to work for them due to the local labour dispute, they show that this must have been a difficult and troubled time for the family. These incidents are part of a long tradition of irritating agrarian intimidation and may have been the reason that an IRA guard had been placed on Ballygroman House in the second half of 1921 according to Nora Lynch.

In considering all of the available evidence, it seems that although Din Din O’Riordan had cast suspicion on the three related Nicholson/Hornibrook/Woods families, there is nothing to suggest that Thomas and Samuel Hornibrooks were suspected of being part of an Anti-Sinn Féin Society or of informing on the IRA, despite the fact that their home had a bird’s-eye view of both the Lee and Bandon Valleys, and was situated directly along the safest IRA route from Cork to the west. Given where they lived, they should have been a prime asset for any British Army intelligence officer and we know that ‘the Intelligence Officer of the area was exceptionally experienced’.

26

Meda Ryan claims that ‘the Hornibrooks were extremely anti-republican and in regular contact with the Essex in Bandon’, but she presents no evidence for this.

27

All their dealings during the War of Independence were with the RIC, the Manchester Regiment in Ballincollig, and the petty sessions court in Farran on the north side of the ridge, so they would have had little reason to be involved with the Essex Regiment. Neither the BMH statements nor the published biographies of the war, nor any other records so far discovered, suggest that the Hornibrooks were actively informing. If there had been evidence, there is no doubt that the IRA had the capacity to find it and the ruthlessness to execute them long before 1922.

6

26 April 1922:

The Shooting on the Stairs

Michael O’Neill, acting Battalion Commander of the IRA in Bandon, Stephen O’Neill (no relation), Charlie O’Donoghue and Michael Hurley arrived at the Hornibrooks’ Ballygroman House some time after midnight on the morning of Wednesday 26 April 1922. According to the inquest, they arrived at around 1.30 a.m. on official business and knocked on the door.

1

After about fifteen minutes someone opened a window and asked who was there. They said they had business with Mr Hornibrook. Someone called out ‘Sam’ from the inside and the window was closed. The door was not opened, and after another fifteen minutes Michael found an open window and climbed in, along with Stephen O’Neill and Charlie O’Donoghue. Michael had a torch. As they climbed the stairs a shot rang out and Michael was hit in the stomach according to Charlie O’Donoghue.

At the inquest that followed, Dr Whelpy gave a detailed description of the wound, reported in the

Cork & County Eagle

, saying that Michael O’Neill had been ‘shot in the chest 2 inches below the collarbone on a downward direction. There was no exit wound.’

2

It is likely that the shot was fired without warning, as stated by Charlie O’Donoghue at the inquest. Michael was carried out of the house, and the three men carrying him headed towards Killumney, about two kilometres away, looking for a doctor or a priest. Michael died on the roadside about 600 metres from the entrance to Ballygroman House. A small cross marks the spot, on the main Bandon–Killumney road, one kilometre to the south of the village.

Later on the morning of 26 April Charlie O’Donoghue returned to Ballygroman House with ‘four military men’. According to the Hornibrooks’ maid, Margaret Cronin, who saw what happened, the house was laid siege to for two-and-a-half hours and was ‘riddled with bullets’.

3

Captain Herbert Woods, who admitted firing the shot on the previous night, was then arrested and taken away with Samuel and Thomas Henry Hornibrook.

4

The following day the coroner’s jury at Bandon found that Herbert Woods was guilty of murder and the Hornibrooks guilty by association. As the evidence of Tadg O’Sullivan to the inquest was that he had sent Michael O’Neill to the house on unspecified official business, this was the only verdict the jury could have brought. Technically, the Bandon IRA was the legal authority at the time and if its members were there on official business they should have been allowed in, no matter the time. Whether this was a fair verdict, given the fact that only Herbert Woods had fired the shot, is a separate question.

The four ‘military men’ who accompanied Charlie O’Donoghue have never been identified. We know from Michael O’Donoghue’s statement that there were approximately nine senior IRA officers in Bandon. Tom Hales, Liam Deasy and, possibly, Tadg O’Sullivan were in Dublin at the time. In his statement to the BMH, Tadg O’Sullivan states that he was ‘Sent to Dublin with L. Deasy and Tom Hales re Pact’ but he was back in Bandon to give evidence at the inquest. Charlie O’Donoghue was definitely in Ballygroman at the time of the shooting and on the following morning, when he arrested the Hornibrooks. Stephen O’Neill had been at Ballygroman when Michael O’Neill had been killed, and was in Bandon for the inquest on Thursday 27 April, the morning after Michael’s body was brought to the church, on Wednesday at 6.30 p.m.

5

Daniel O’Neill, the inspector of the Irish Republican Police at Bandon (and Michael’s brother) attended the inquest. Another brother, Jack (John) O’Neill, and Con Crowley were two of the other officers recorded as IRA officers by Michael O’Donoghue in February, and Mick Crowley had replaced Michael O’Donoghue as engineering officer of the 3rd West Cork Brigade stationed at Bandon at the end of March. It would be surprising if the car that returned to Ballygroman to arrest the Hornibrooks did not include at least one of Daniel O’Neill, Jack O’Neill, Con Crowley, Stephen O’Neill, Michael Hurley or Mick Crowley, but there is no direct evidence of this. Charlie O’Donoghue could have taken four ordinary volunteers with him. Nobody knows.

IRA officers provided an honour-guard for Michael O’Neill’s body on Wednesday and Thursday, and his funeral was a major military ceremony through the centre of Bandon on Friday 28 April. The chief mourners were Mr and Mrs Patrick O’Neill ‘of Maryborough [sic, actually Maryboro]’, Kilbrittain. His brothers Denis (Sonny), Jeremiah and John (Jack) also attended. Patrick Jnr is not mentioned as attending, but his sisters Molly and Maud were present. Floral tributes were sent by Tom Hales, Liam Deasy, Denis Lordan, Denis Sullivan and Con Lucey, among others. Charlie O’Donoghue and his brothers and sisters also placed a wreath on the grave. According to the

Cork Examiner

, ‘his coffin was carried by his brother officers, and followed by thousands of Volunteers, and a firing party with arms reversed’.

6

He is buried beside the church in Kilbrittain in the republican plot.

What exactly happened to the Hornibrooks and to Herbert Woods is not known. Everyone in the area knows the folklore that has arisen around the kidnappings. All the known versions of the rumours are presented in this chapter. While they vary wildly in detail, they all agree that the Hornibrooks were taken to Templemartin and killed afterwards. Some suggest that Woods and the Hornibrooks were buried in Newcestown; others suggest they were buried further east or further west.

Peter Hart wrote that Charlie O’Donoghue returned to Ballygroman with rope, which implies that someone was going to be tied up or hanged. At the time at which Hart was writing there was no evidence for this, except an anonymous interview and local folklore.

7

This folklore had also suggested that Woods was dragged after the car in revenge for the same having been done to IRA ‘bad boy’ Leo Murphy at Waterfall in 1921.

8

Another version of the story appeared in the

Cork Hollybough

in 2002, written by R. D. Kearney, who stated that ‘a retired British Army Major named Hornibrook lived there with his wife, son, daughter and her husband Capt. Woods’.

9

He further stated: ‘After some negotiations the mother, daughter and maid were allowed to go free, but the three men were reportedly subjected to violent torture before being taken to a secret location where they were summarily courtmarshalled and executed.’ As Thomas Hornibrook was a widower in 1911, and his only daughter, Matilda, was married to Edward Woods, who lived in Crosses Green, this version cannot be accurate. Matilda was not in the house on the night.

10

A different version was told to Dr Martin Healy, another owner of Ballygroman House, and his source was Father Crowley, the locally born parish priest of Ovens, who was four at the time of the shootings. He was told that Michael O’Neill had been carried on a door to the neighbouring house, where he died in the yard, and Herbert Woods was taken into the same yard the following morning and ‘half hung between the shafts of a cart before being tied to the back of the Hornibrooks’ car and dragged behind it’.

11

Three similar versions of these rumours were told to local historians. Nora Lynch’s main source was Mr O’Halloran of Ballincollig. Mr O’Halloran was not born in 1922, but the information was told to him by members of his family. Nora Lynch said that she spoke to Mr O’Halloran, who had lived in Templemartin

12

near to a disused forge called Lynch’s Forge.

13

He told her that shortly after the disappearance of the three men from Ballygroman, a woman named Mary Horgan was passing the forge and heard men screaming.

14

She looked into the forge and saw men covered in scars. They were tied to a pig trough. Not knowing what to do, she went to the priest in Cloughduv and demanded that he return to the forge with her. Upon seeing the men, he blessed them and went to the commander of the local IRA to demand that they be moved. That night a group of IRA men arrived at the forge with carts and removed them. The O’Hallorans were told a few days later that they had been taken to Farranthomas bog, Newcestown, and made to dig their own graves. The O’Hallorans were also told that the men were not shot, but were axed into the grave and dismembered.

15

Nora Lynch also said that another local rumour suggested that Michael O’Neill had been drinking with others in Killumney and had walked up the hill to the Hornibrooks’ house to borrow Mr Hornibrook’s car to get back to Bandon. Hornibrook had taken the carburettor (magneto) out of his car in case it got damp overnight. When O’Neill asked for the carburettor, Hornibrook, who had no idea who he was, refused. O’Neill broke into the house, and Herbert Woods grabbed a gun on the stairs. In the struggle to control the gun, it went off and O’Neill was shot in the stomach. The medical evidence at the inquest shows that O’Neill was shot in the chest from above and that the bullet pierced his heart, so this element of the rumour is not correct.

According to a different story also told to Nora Lynch, on the morning after the shooting a man from Ovens Bridge and two men from different families in Walshstown in Ovens, who were friendly with Michael O’Neill, went to the Hornibrooks’ house. After a mêlée outside the house, in which one of the Hornibrooks received a broken nose from the butt of a rifle, the Hornibrooks were bundled into their own car and driven away to the west. The source for this was John Lucey of Grange, Ovens, who worked for the Hornibrooks. He said that when he saw his employer being attacked, he went to help him and was told to clear off if he knew what was good for him. Nora Lynch states that he told her the story when she was a young girl and he was a neighbour of hers. She also states that the killings were regularly discussed in the parish and that ‘everyone knew the story’. There is no documentary evidence to support this information except that an agricultural labourer named John Lucey is recorded as living in Grange in the 1911 census.

16

When Nora Lynch went to write the story twenty years ago, she was told that she would be sued and she decided not to proceed.

Seán Crowley of Garranes, Templemartin, in his history of Newcestown published in 2005, provides another version of the story that was related to him. He states that the three men were taken to Scarriff, Templemartin, and court-martialled.

17

In his interview with me he said that while the men were held in Scarriff, Julia Hallahan and Margaret Murphy of Cumann na mBan provided tea and food for them. They were held at a disused house on Daniel Horgan’s farm, which included Scarriff House. He had bought this from his neighbours, the Good family, in 1919.

18

Mr Horgan – who was in Bandon on business – was told that armed men were at his house. When he returned home he recognised some of the men holding the Hornibrooks, but he never revealed their names. According to Seán Crowley, they were being guarded by the Quarry’s Cross Company (East Newcestown) of the IRA, which would have been normal if they had been arrested by the Irish Republican Police and taken into the company’s area. Their ‘prison’ was the disused workman’s house on his farm which later became known as ‘the College’ because Irish classes were held in it. He states that they were then seen being driven through Quarry’s Cross and they were killed ‘in the general Newcestown area’. He also suggests that if Michael O’Regan of the Ovens IRA had been protecting the Hornibrook house from agrarian agitation, as was normal, then the events that night would not have happened, as the Hornibrooks lent their car to him on request. However, in O’Regan’s witness statement to the BMH, he makes no mention of the incident, despite the fact that the statement covered events up to May 1922.

19

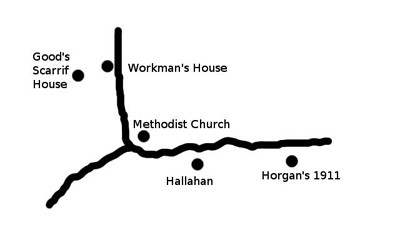

A little sketch map was drawn during Seán Crowley’s interview, identifying where all the witnesses were living. The distance between Scarriff House and Horgan’s original farm is about 500 metres. The disused workman’s house is close to Scarriff House. The tiny Methodist church building is still there today but now used as a private home.

Donal O’Flynn, during his interview with me, paused and said, ‘You must remember I grew up with the Hornibrooks – their story – I’ve known it for as long as I can remember.’

20

He was told that the bodies are buried in the locality, in the same field as two ‘informers’, one from the Brinny ambush (possibly Crowley) and the other a man from Bandon (whose name he was unable to provide).

21

He was also able to provide a great deal of information about the killings and the Hornibrooks, which both confirms and clarifies much of the information in the other rumours and stories.