Massacre in West Cork (4 page)

Read Massacre in West Cork Online

Authors: Barry Keane

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Ireland, #irish ira, #ireland in 1922, #protestant ireland, #what is the history of ireland, #1922 Ireland, #history of Ireland

Michael Collins

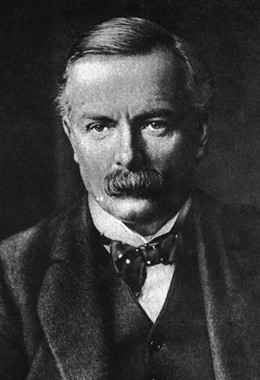

David Lloyd George

Lloyd George’s statement to the House of Commons a week later is candid about the working out of these peace negotiations. When he spotted an apparent weakness on the Irish side he gambled that military advice of imminent victory was correct and drew back from a domestically difficult deal. Even though he had worked out what needed to be done, he decided to ‘haggle over the price’.

30

Two days later, with the pictures of a smouldering Cork burned by a rampaging mob of out-of-control Auxiliaries and British soldiers splashed all over the newspapers, he must have felt very foolish indeed.

Despite these negotiations, in late 1920 the British military in Ireland were so convinced that they were winning that they had delayed the traditional winter concentration of their troops in large central barracks from the start of October to 1 December. However, thirty-three soldiers, out of a total of 162 killed in the war, were then killed in these months, and this excludes the much larger RIC and Auxiliary casualties. This upsurge in the number of deaths in winter 1920 was one of the reasons that the British Military High Command in London ignored their generals in Ireland to recommend a truce as the most sensible option.

By late 1920 the analysis of the British Military High Command was that while the British could win the current phase of the rebellion, it could break out again at any time. They would have to station far too many troops in Ireland relative to its value to the empire.

31

Strategically, how much of a threat was a partitioned and independent Ireland actually going to be in an era of air power? Chief of the Imperial General Staff Sir Henry Wilson had a different view, but he was unionist to the core and had been a leading member of the Curragh Mutiny. However, ultimately a choice had to be made in response to the sustained challenge presented by Sinn Féin and the IRA: complete repression or freedom.

Lloyd George had a far better understanding of what was at issue for the British than most. When members of the cabinet wished to amend the Government of Ireland Act in October 1920 to give the Irish power over Customs & Excise, he dismissed this by pointing out that to concede taxes meant that they would have nothing left to negotiate with. Taxes meant independence.

32

The alternative to conceding ‘independence’ was military repression, and if force failed he would have to concede independence in all but name rather than threaten Britain’s other possessions. This was real politics.

The subtlety of the war in its later stages can be seen from an attempt by General Strickland, the British commander in Munster, to secure his northern flank by proposing a local armistice for County Kerry in February 1921. This would allow him to turn the hammer fully on West Cork. As with any such offer the intelligence officer in Kerry decided to pursue it and asked Collins in Dublin for instructions before he took the offer to Paddy Cahill, Officer Commanding the Kerry Brigade. Collins replied:

Armistice – This sort of thing is going on a good deal. It would be very easy for General Strickland to get rid of his troubles by giving such a guarantee, after which the Black and Tans would be quite free to murder; and as for flooding the place with troops, it can be conveyed to General Strickland that we know he can do no such thing, for he is continually begging for more men from his own Headquarters. The General seems to be a good propagandist, and a good bluffer. It might also be suggested to him that if they cannot restrain the Black and Tans, they can remove them.

33

It is clear from this exchange that neither Strickland nor Collins were fools and that they had both become very good at their jobs by this stage.

By the start of 1921 the British had improved their military position by structural changes in their intelligence network. Pieces of information which had been going to three separate groups of people in Dublin were now concentrated in the hands of the local intelligence officer, who could react more quickly to relevant facts.

34

Between February and May 1921 one pro-establishment paper, The Irish Times, reported no less than five major finds of republican documents. A Cork & County Eagle report of 5 March gloated that the proceedings of an IRA meeting involving the Cork, Tipperary, Kilkenny and East Limerick Brigades, held on 6 January 1921, had been captured; the reporter believed that this showed the IRA was in disarray and on the point of defeat in Cork.

This optimism seemed to extend to the British government. In April 1921 when the Lord Chancellor, Lord Birkenhead, met a ‘peacenik’ delegation, including the Archbishop of Canterbury, to work out a way forward, he made it clear that the cabinet believed that the British were winning the war.

35

However, the IRA was just as effective as its opponents in the intelligence war. Perhaps one of the most extraordinary documents in the BMH collection is the witness statement of East Limerick IRA intelligence officer Lieutenant Colonel John MacCarthy, which includes a copy of the British

Military Summary for May 17th 1921

for Munster.

36

The capture of this report meant that everything the British knew about IRA activity for the early weeks of 1921 became known to the IRA. Three good examples of what the report contains show how much accurate information was available to the British, as the details are confirmed by many BMH witness statements, but they also reveal an element of wishful thinking:

37

Rebel Flying Columns are suffering heavily from scabies. In order to cure this disease men are returning to their homes and lying up there for a week or two. It is essential that these men be kept on the move by frequent visits to their houses [p. 4].

A big drive was carried out by the Crown Forces in the Kilmacthomas [County Waterford] area on the 6th inst. The drive failed to round up the I.R.A. unit which has been operating in that area, yet there is no doubt that will have a good effect in a part of the country where Crown Forces are seldom seen. One old loyalist farmer made remarks to this officer and said that such a parade of troops would make the hooligans going round the country look very small [p. 5].

The Brigade Mobile Column returned on Thursday 12th, May after a tour of a part of the Brigade area. No armed body of rebels was encountered but the local company at Aherla was rounded up almost to a man. Frank Hurley Commandant No. 1 battalion (West) Cork Brigade and a prominent leader of the Flying Column was shot. It is hoped to obtain information as to whether the Brigade Column made any difference to rebel plans for attacks on Barracks, and caused them to be postponed. [p. 6].

The British report also shows the prevalence of British informers within the rural population.

Other documents in MacCarthy’s statement include the minutes of the January divisional meeting, which can be cross-checked with the Cork & County Eagle report mentioned earlier, and various other intelligence reports from East Limerick. Most noticeable in these documents is the amount of detailed information both sides had gathered about each other. All these reports show that the war was a far more open and fluid affair than is generally suggested. The boundary line between ‘them’ and ‘us’ appears to have been impossible to draw.

The British had also improved their military position by the middle of 1921. The first deployment of the Auxiliaries in Ireland as an aggressive raiding force in September 1920 had increased the intensity of the war

38

and forced it to a conclusion, though not in the way intended. In 1921 the combination of the long summer days and the introduction of large, highly mobile British Army flying columns also meant that it was harder for the IRA flying columns to gather together, or to plan ambushes, without being attacked. The ground was dry from a drought, and this meant that the British could take to the fields and drive around the IRA’s favourite defensive tactic of trenched roads.

39

Potential ambushes had less chance of success as the area could be quickly flooded with British troops and (to a much lesser extent) aeroplanes, once the IRA was detected. In some cases the British could almost sneak up on the IRA, as happened at Crossbarry on 19 March 1921, one of the largest engagements of the War of Independence;

40

on this occasion, however, the West Cork IRA flying column escaped the attempt by, according to Tom Barry, more than 1,300 British troops to encircle it at this rural crossroads between Cork and Bandon.

41

The troops had converged from their main barracks at Cork, Ballincollig, Bandon and Kinsale during the night and nearly caught the column off guard. William Desmond, who was captured in the first engagement, noticed that the troops ‘had bags or sacking twisted around their feet to deaden the sound’.

42

The ferocity of that fight and the discipline and order of the escape from a very tight trap are credited on the Irish side as being one of the main catalysts for the Truce on the British side.

If the British Army had only had Ireland to deal with, it could easily have contained the Irish insurgents although it could not actually defeat them. If insurgents retain sufficient popular support, it is possible to keep low-level wars going for generations: for example, the Vietnamese fought a thirty-year war of liberation against the French and the Americans (between 1943 and 1973), and the Algerians defeated the French between 1954 and 1961. In both cases the weaker side could not necessarily win, but was impossible to defeat. The events of the later Irish Civil War during 1922 and 1923 proved this in the negative: once the anti-Treaty side lost popular support, it would lose that war.

Senior members of the British military understood just how difficult and expensive continuing the war would be. In his statement to the BMH, Captain Edward Gerrard, who was aide-de-camp to Sir Hugh Jeudwine (Officer Commanding the 5th Brigade in Ireland), described the situation from the British perspective in June 1921:

I remember Sir Hugh Jeudwine saying that the estimate for the whole of Ireland was 150,000 men in 1921. Himself and Strickland required two Divisions each. That was 150,000 men between them. They wanted to divide the whole country into areas with barbed wire.

I rode through Carlow and Kilkenny with the Cavalry Brigade, 10th Hussars, and 12th Lancers, in June and July, 1921. I was actually in Carlow when the Armistice came. Every field we got into was made into enclosures by trees cut down. I remember saying to the Major, ‘if it is like this within twenty miles of the Curragh, what is it going to be like in Cork?’ The Hussars could not see anyone. There was no one to attack. It was all so elusive.

43

By July 1921 both sides seemed to realise that if the IRA survived until the long nights of winter the tide of war would once again swing back in its favour. Even the main proponents of a military solution in late 1920 had changed their mind by this time and were absolutely insistent that the war needed to be won by September 1921 at the latest. Macready told the cabinet that if the war was not won by the end of the summer ‘steps must be taken to relieve practically the whole of the troops together with the great majority of their commanders and their staffs. I am quite aware that the troops do not exist to do this …’.

44

For the British, Lloyd George’s dilemma of October 1920 remained: meet with Sinn Féin and agree a settlement along the lines suggested by W. E. Wylie of Dominion Home Rule with fiscal independence in all but name, or take the advice of General Tudor that the war could be won by the Auxiliaries and Black and Tans before the end of summer 1921.

45

In October Lloyd George had chosen to follow military advice; now he chose the political solution.

While there is no doubt that the British were winning at the time of the Truce, their success was dependent on too many contingencies to suggest that this situation was guaranteed or likely to continue. After all, the first shower of rain would begin to swing the advantage back to the IRA, and Macready’s self-imposed deadline of September was less than eight weeks away.