Master Thieves (21 page)

Authors: Stephen Kurkjian

There has long been evidence linking Donati to the Gardner heist. His name had surfaced in connection with the

museum in 1997 because of his association with legendary Boston art thief Myles Connor. But this account provided by the source, of Donati visiting Ferrara to tell him of his plans to get him out of prison, has never been disclosed before.

The story is a reminder of the importance of one of the most elemental aspects of detective work. From the time Louis Royce first began casing it in 1981, the Gardner Museum's poor security was an opportunity staring every Boston criminal in the face. Turner and Guarente may have fit the profile. And Rossetti may have had the means. But in the person of his recently arrested boss, Bobby Donati had something no one else had: a motive.

_______________________

Vinnie Ferrara

is not the only person who believes Bobby Donati was one of the two men who carried out the greatest art theft in world history. Myles Connor, the son of a police chief who turned into a legendary art thief in New England, says he was told the same thingâby Donati's alleged partner in the crime, a similar ne'er-do-well named David Houghton.

Houghton had long been friends with Connor, sharing Connor's love of rock music and often accompanying Connor to gigs his band would get in and around Boston. Like Donati with Ferrara, Houghton had taken it personally when Connor was arrested on a drug deal gone wrong in 1989 and was sentenced to ten years in federal prison. Around the same time in mid-1990 that Donati was visiting Ferrara at the PlyÂmouth House of Correction to tell him of the Gardner robbery, Houghton was flying to Lompoc federal prison in southern California to visit Connor.

“You think I was going to let you rot to death here?” Houghton asked Connor. “Me and Bobby Donati did that

score, and we're going to use the paintings to get you out,” Connor recalled Houghton telling him.

To this day, Connor believes Donati was involved in the Gardner theft, saying they often discussed how vulnerable the museum was to being ripped off. Also, he says when they first met in the early 1970s, Donati was already familiar with how useful stealing valuable art was. In his book,

The Art of the Heist

, Connor wrote that Donati had shown him how easy it would be to break into the Woolworth Estate in Monmouth, Maine. In May 1974 they stole five stunning paintings by Andrew Wyeth and his father, N. C. Wyeth from the estate.

Connor says he stashed the Wyeth paintings with his girlfriend in western Massachusetts, then went looking for someone who was interested in purchasing valuable, albeit stolen, art. After rejecting overtures from several gallery owners, Connor says, he thought he had found the right person, on an introduction through Donati. The two men agreed to meet in the parking lot of a Cape Cod shopping center.

But instead of being interested buyers, the individual was an undercover FBI agent, and Connor was arrested.

Once out on bail, Connor continued his life of crime, robbing a bank and then setting his sights on Boston's Museum of Fine Arts. With the trial for his theft of the Wyeth paintings only months away, Connor figured the only way he could gain leverage against federal prosecutors was to make an even bigger score.

On a sunny April morning in 1975, Connor drove with two friends to the MFA in Boston's Fens neighborhood. With one pal parked outside, Connor and another man made their way into the museum and headed for the second floor. There they pulled a large Rembrandt painting called

Girl with a Fur-Trimmed Cloak

from the wall and ran from the building. A guard gave chase and quickly caught up to the pair. He grabbed the painting but was bludgeoned with the butt end of a rifle and decided to

give up his grip rather than risk his life for the painting. Connor stashed it underneath the bed of his best friend's mother.

Several months later, with the federal trial for his role in the theft of the Wyeth paintings about to take place, Connor reached out to the Massachusetts state police and the assistant US attorney prosecuting the federal case through his lawyer, Martin Leppo. If the authorities entertain a plea deal, Leppo told them, Connor would facilitate the return of the Rembrandt.

“Negotiating for stolen art is a controversial subject,” Connor wrote in his autobiography. “Certainly none of them [in law enforcement] wanted to be seen making a deal with a convicted cop shooter and known art thief.”

But that's exactly what Connor and Leppo were able to arrange. In exchange for the return of the Rembrandt, prosecutors dropped the charges of bail jumping against Connor after he had failed to show up for one hearing. And the US attorney's office agreed to recommend that the four-year sentence against Connor in the Wyeth thefts run concurrently with the sentence imposed for the MFA robbery.

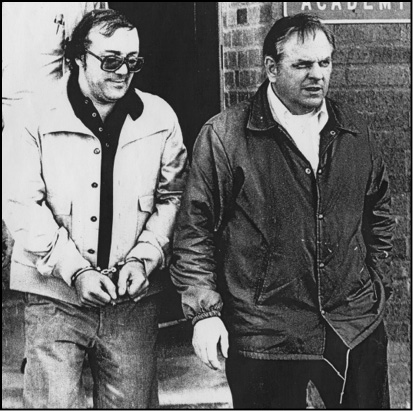

Robert A. Donati (following an arrest in the 1980s) cased the Gardner Museum for robbery with legendary Boston art thief Myles Connor Jr., with whom he had robbed a Maine estate of valuable paintings in the 1970s. Donati was amazed when he learned that Connor's lawyer had been able to secure a plea deal with federal authorities by promising to return stolen artwork.

Donati clearly marveled at Connor's ability to swap the return of a stolen masterpiece for leniency within the federal and state court systems. At the same time Connor was completing his sweetheart deal with the US attorney's office in Boston, Donati was seeking something similar from a federal judge. He wrote to US district court judge W. Arthur Garrity Jr., asking for reduction in a ten-year sentence Garrity had imposed on him following Donati's guilty plea on stolen securities charges. Donati had been serving a state prison sentence, during which he'd participated in a work release program. If Garrity checked with state correction officials, Donati argued, he would find that Donati had become a model prisoner while serving in that program, and deserved a reduction in the federal prison term he was now facing.

“I am not asking that I be released overnight, but only that I be afforded some relief so I can go back into work release and continue my upward strides so that I need never come back into these places again,” Donati wrote.

But unlike Connor, Donati had nothing to trade for his freedom, certainly no Rembrandt. Garrity denied Donati's motion.

Despite their disparate treatment by the court system, Connor and Donati remained friends both inside and outside prison in the ensuing years. After discussing how easy it would be to rob the Gardner, the two men even visited the museum on several occasions, with Donati paying particular attention to the security desk and the guard manning it, Connor said.

What's more, Donati was dropping suspicious hints to others at the key time. Just before the robbery took place, Donati walked into a Revere, Massachusetts, social club called The Shack, run by his close friend, Donny “The Hat” Roquefort. Donati carried a large paper bag under his arm and Roquefort insisted that Donati show him what was inside. When Donati resisted, the larger and tougher Roquefort approached him and grabbed the bag, and ripped it open. Two police uniforms fell out of it.

“What the hell, have you joined the other side?” Roquefort shouted at Donati playfully, and grabbed the taser stun gun he usually kept beneath The Shack's front counter. He pressed the taser playfully into Donati's side and pulled the triggerâit must have been the first time Roquefort had used the taser, as the blast of the gun did quite a number on Donati, burning right through his coat, shirt, and into his skin.

Donati never explained what he was doing with the uniforms, but at least one person there that day remembered the odd encounter with the taser gun. And this source said there was one other person with Donati at the Shack that day: Bobby Guarente.

Indeed, according to members of both men's families, Guarente and Donati had long been close. Donati's close relationship with Guarente provides the most tantalizing clue to his possible connection to the Gardner theft. In the FBI's view, Guarente played a central role in the heist. He received the paintings, they believe, from small-time hoods such as Carmello Merlino and David Turner at Merlino's Dorchester auto body shop. Then, they believe, Guarente held onto the paintings at his home in Maine until the early 2000s, when, after learning he had cancer, he turned the paintings over to Robert Gentile, the low-level hood based in Manchester, Connecticut. In the late 1990s, when Guarente ran a cocaine distribution

ring out of a home in suburban Boston, Gentile worked for him as a cook, poker dealer, and part-time security man.

Elene Guarente, Guarente's widow, remembers Donati fondly. “My Bobby was close to Bobby Donati. They knew each other as teenagers. Bobby even brought his son on a fishing trip up to our place in Maine.”

When Donati disappeared in September 1991, Guarente was one of the first individuals that members of Donati's family called to see where he might be.

According to sources who knew him, Donati wasn't prepared for the level of police attention devoted to the Gardner theft. It's easy to envision the scenario: afraid for his safety, he buries the paintings for a time, until the furor died down. Then, sometime in 1990 or 1991, he passes one or several of the works to someone he trusts: Bobby Guarente.

Earle Berghman, the close friend of Guarente's in Maine, is convinced the friendship between Guarente and Donati included dealings on the Gardner paintings. “Bobby Donati did that job,” he said of the Gardner theft. “Then he gave some of them [paintings] to Guarente when he became concerned about his own safety. Bobby Donati knew he was a marked man. Why else would he give over the thing he valued mostâthose paintingsâto Bobby Guarente? Then, before Guarente died, he passed them on to Gentile in Connecticut.”

The brutality of Donati's death is particularly troubling for his family members, because he was under FBI surveillance in the weeks before it. He was attacked as he walked onto the front porch of his modest home on Mountain Avenue in Revere, a working-class Boston suburb. His body was found bludgeoned and stabbed twenty-one times, stuffed in the trunk of his white Cadillac, about a half mile from his home. Donati had become withdrawn and anxious and seldom ventured out of his house before his death. He'd told one associate about a month before he was killed that he'd noticed

two suspicious men in black running suits hanging around his house and figured they were plotting to kill him.

Why the FBI had Donati under surveillance at this time, or whether agents suspected he had been marked for assassination, is not stated in his FBI file. However, the files note that Donati owed a large amount of cash to local bookmakers. Others speculated that with Ferrara, his protector, locked up, Donati had been attacked by members of the rival gang headed by “Cadillac Frank” Salemme. No one has ever been charged in Donati's murder.

Lorraine Donati is haunted by her brother's savage killing and has tried without luck to get answers from investigators about the circumstances of his death, and even whether he might have had anything to do with the Gardner case.

“One bullet could have accomplished what they were looking to do,” Lorraine Donati says ruefully of her brother's execution. “No one has to be stabbed and beaten like that unless there was some dark secret behind it. I go to bed every night angry or sad that I don't know, and I seem to be the only one who feels that way.”

As for Ferrara, the theft of the Gardner artwork made no difference in his years in prison. He bounced between federal prisons throughout the country during the next decade, but after learning that one of his closest associates had been a government informant against him, he decided to appeal his conviction. In going through the evidence against him, his lawyers learned that a key witness against Ferrara had recanted his testimony to the police, that Ferrara had not ordered the killing of his associate. However, that information had never been turned over to Ferrara's lawyers.

In 2005 a federal district court reopened Ferrara's case after long-buried evidence surfaced showing Ferrara had no involvement in the killing of a young gang associate who had been dealing in drugs. US district judge Mark L. Wolf took two

actions once he learned of the new evidence: He recommended that the Justice Department investigate the federal prosecutor who'd kept the information buried for sixteen years, and he found that Ferrara had served long enough on his racketeering charges and should be released immediately.

After listening to five hours of recorded telephone conversations Ferrara had made while in prison during the previous year, Wolf was convinced that Ferrara was sincere in his promise to go straight. The phone calls “demonstrate that Ferrara remains deeply dedicated to his family, and is both able to obey rules and determined to do so in the future,” Wolf said.

“Having had the opportunity to observe Ferrara closely over many years, this court finds Ferrara's statement to be sincere and meaningful,” Wolf said of the former mob leader's pledge to live a law-abiding and peaceful life if he was released from prison.