Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume 2 (78 page)

Read Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume 2 Online

Authors: Julia Child

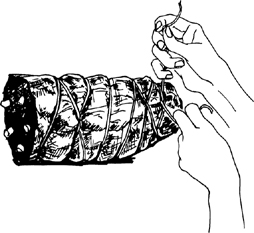

Insert as many other fat-strips as you wish—a piece of meat 4½ to 5 inches in diameter will take 4 to 6. |

|

BEEF TENDERLOIN

Filet de Boeuf

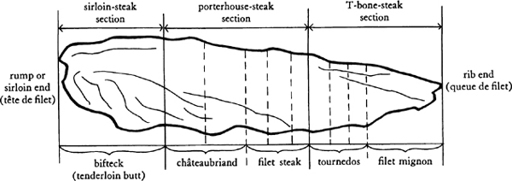

The central and the right-hand sections together, in this drawing, constitute what is usually meant in American retail meat markets by a whole tenderloin: to be technically correct, it should be called the whole short-loin tenderloin. It weighs 4½ to 5 pounds untrimmed, and contains 3½ to 4 pounds of usable meat. When you are serving 6 to 8 people, you may wish the central section only,

le coeur du filet

, which will give you a roast of 2½ to 3 pounds that averages 8 to 10 inches in length. For 10 to 12 people you will need the whole piece, and may fold the last 2 inches of the tail (right-hand side) back upon itself as illustrated further on, to make a 12-inch roast that is 3½ to 4 inches in diameter when tied.

If by chance your market does cut whole sides of beef, you may be able to buy the whole tenderloin with butt end attached. Depending on the cutting method, the butt alone contains only a little over 1½ pounds of usable meat, although it weighs slightly more than 3 pounds; to be deprived of it, therefore, is no great loss, tenderloins costing what they do.

TRIMMING A TENDERLOIN

Most meat markets will usually trim, tie, and lard the tenderloin for you, but you should be able to do it yourself so that you will know how the meat is constructed.

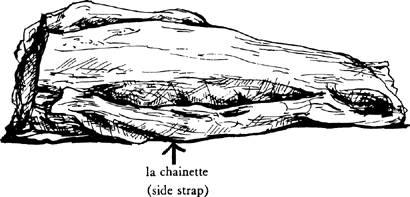

When you have an untrimmed tenderloin in front of you, you will note a definite difference in the 2 long, flat sides. On one there is a series of thick ridges and depressions more or less marbled with fat depending on the grade of the beef carcass; this side is where the filet rested against the 6 vertebrae of the backbone in the small of the back. We shall call this the underside. The other side, which we shall call the top, will have some loose fat clinging to it, mostly at the large end and at the edges; along the central length you will see the main muscle of the tenderloin, covered with a shiny membrane. Starting on this side, rather gingerly pull the loose fat from the top of the membrane and along the edges, being very careful not to detach the 2 long straps of meat lying against each side of the main muscle. The smaller of the two straps is flattish, as though it were a flaplike continuation of the underside; underneath the larger of the straps,

la chainette

, is a line of fat that should not be disturbed because it attaches the meat to the main muscle.

This is the whole short-loin tenderloin (

central and right-hand portions of diagram

), showing the 2 chains of meat attached to the length of the main muscle. Do not worry too much if you partially detach them; you are going to tie the meat anyway before roasting, and the ties will make the chains adhere. Although some people advise removing these chains of meat, you will diminish your roast by more than half its weight if you do so: you will end up with 2 thin strings of meat good only for sautéing or skewering, and your

filet

proper will weigh only 2 pounds. This is entirely a matter of your own preference, of course; we leave them on.

After pulling excess fat from the top of the meat, you must also remove the shiny membrane that covers the main muscle on this side, and as much of it on the large chain of meat as you easily can. Remove the membrane in half-inch strips the length of the meat, scraping under it with a small, sharp knife. (If you happen to have an actual whole tenderloin with butt included, you will notice that the main muscle with its membrane continues into the butt for several inches before it loses itself. You may wish to separate this main muscle from the rest, making it a continuation of your roast. The surrounding meat will make excellent steaks or sautés. It is rather a question of how it looks to you while you are trimming: as long as all the membranes are removed, all of the meat is good either for roasting or sautéing.)

Finally, inspect the underside of the meat and remove what you consider to be obviously excess fat; a reasonable amount left on will help to baste the meat as it roasts. Meat is now trimmed and ready for cooking. The following directions are for roasting; directions for steaks are in Volume I, pages 291 and 296–300. Do not forget the sautés of beef, Volume I, pages 325–8, which are delicious for meat from the butt, the chains, and the tail; you may also adapt sautés for any leftover cooked tenderloin.