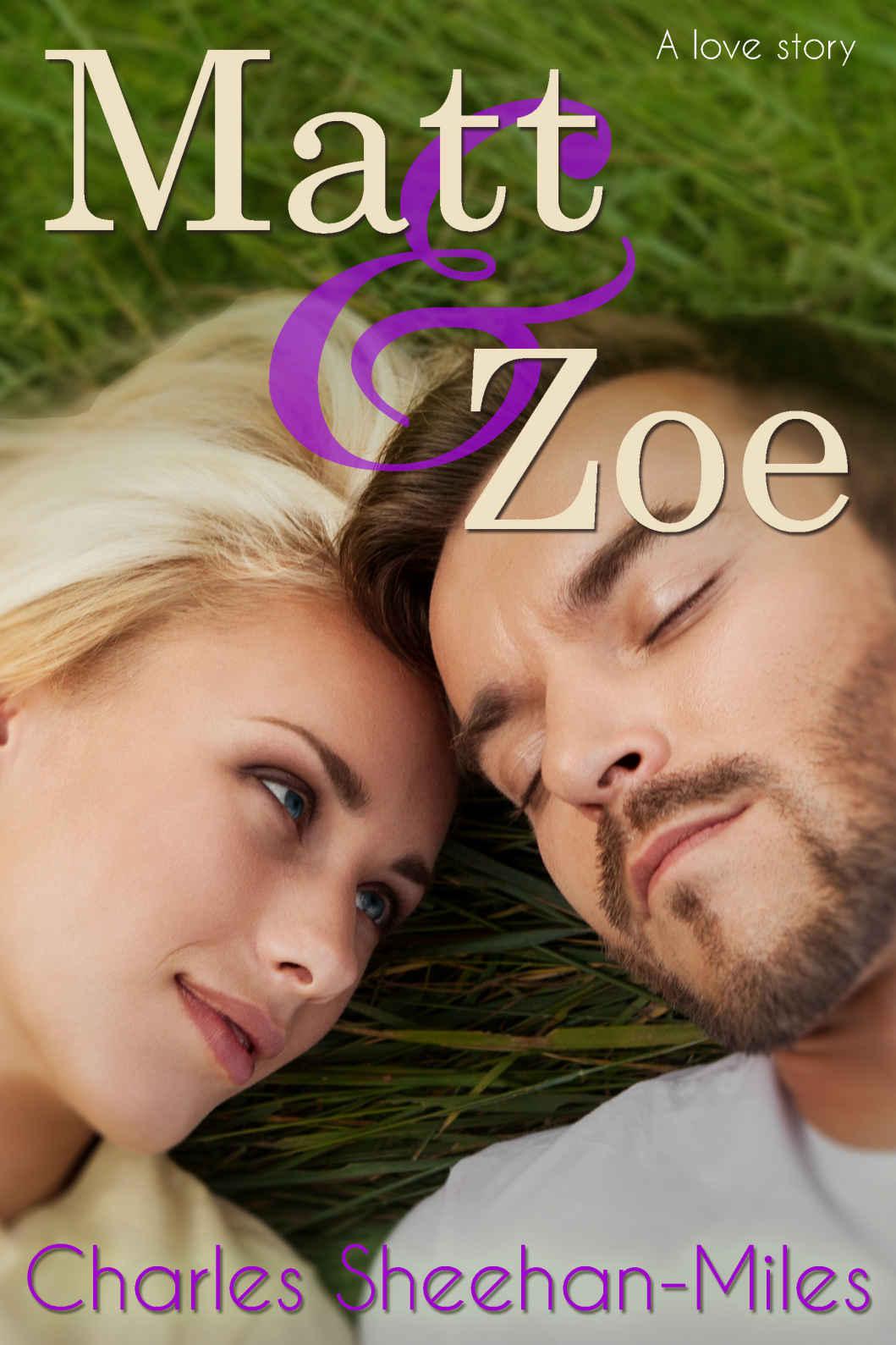

Matt & Zoe

Authors: Charles Sheehan-Miles

by

Charles Sheehan-Miles

Books by Charles Sheehan-Miles

The Thompson Sisters

A Song for Julia

Falling Stars: A Thompson Sisters

A View From Forever

Just Remember to Breathe

The Last Hour

The Thompson Sisters / Rachel's Peril

Girl of Lies

Girl of Rage

Girl of Vengeance

Fiction

Nocturne (with Andrea Randall)

Republic: A Novel of America's Future

Insurgent: Book 2 of America's Future

Prayer at Rumayla: A Novel of the Gulf War

Matt & Zoe

Nonfiction

Saving the World On $30 A Day: An Activists Guide to Starting, Organizing and Running a Non-Profit Organization

For the women who served

in Iraq and Afghanistan

Chapter One

Miss Annoying (Zoe)

The brakes on Nicole’s patrol car squeal as she brings it to a gentle stop in front of the unmarked building. It’s an old three-story white house with black shutters, with three cars parked in the gravel driveway. From the outside, there’s nothing to indicate this is an emergency shelter for children.

South Hadley is well outside Nicole’s jurisdiction, but all the same, I’m glad she’s here with me. The sunlight flashes off her badge as her shoes crunch in the gravel. We walk to the front door, and I feel tension in my chest. Nicole knocks, and I cross my arms. The sunlight is glaring down, hot against my shoulder, but I’ve been in much worse heat. My tension isn’t from the heat out here, it’s from what I might find inside.

The front door opens. A tired looking woman stands there, forty or so, with ill-fitting clothing.

“Can I help you?”

“I’m Officer Banks. This is Zoe Welch; she’s here to pick up her sister.”

The woman’s eyes dart to me, scanning over my uniform—rumpled from forty-eight hours of travel—then to Nicole—then back to me. “Miss Welch… my name is Linda Whitney. Come in, please. You’re … younger than I expected. I was led to believe you’re a Sergeant in the Army?”

I shrug. “I am. Or was—the Army discharged me yesterday.”

She leads us into an entry room. It’s bare, with refinished pine flooring, white walls and plain furniture.

“Please, wait here, and I’ll go get her. Um… do you have any identification?”

I open my functional purse and pass over my Army Reserve identification. I don’t have a current driver's license. I'll have to take care of that soon.

Linda frowns, looks at the photo on the identification, then back at me, as if she doubts I'm the person in the photo. I don’t know why—my Army Reserve ID was printed yesterday—the photo is clearly me. Without a word, she passes the ID back and I tuck it away. She walks out of the room, shutting the door behind her with a loud thump.

“Wicked friendly, isn’t she?” Nicole asks. Her tone is dry.

“I guess.” Another time I might have laughed, but right now it’s hard to have any kind of sense of humor. I’ve slept little since Captain Wilson awakened me in the Hardy Barracks in Tokyo forty-eight hours ago.

Sergeant Welch. I regret to inform you your parents were killed in an accident.

I have to hand it to Captain Wilson and the Army—they moved quickly. My first question when I learned my parents were dead was:

where is Jasmine

? Mom and Dad didn’t have any siblings, and our nearest relatives are some distant cousins in California.

The initial answer terrified me: nobody knew where she was. Within a few hours I learned that Jasmine was in an emergency shelter. The Army granted me an immediate hardship discharge and flew me home. I skipped the normal out-processing—Captain Wilkins and my First Sergeant stepped in and took over everything so I could be on a plane as quickly as possible.

I sway a little on my feet as the door opens and the sourpuss woman walks back in. Jasmine enters the room next. She’s downcast, hair hanging in her eyes, and wearing a clean but threadbare dress. At eight years old, Jasmine is about four and a half feet tall and weighs sixty pounds. Her wispy, dirty-blonde hair looks limp and lifeless.

“Jasmine,” I whisper, dropping down to one knee.

Her face whips up and her blue eyes widen, then in a blur she runs toward me, crying out the word, “Zoe!” in a choked, grief-stricken wail. She hits me hard and I almost fall backward. She begins to sob.

“It’s okay,” I whisper. “It’s okay.”

It isn’t okay.

The accident was bizarre enough it made the news all over. I’d read the details. A truck full of premium commercial ovens hit a pothole, swerved across the road and rolled, throwing a one-ton stainless-steel gas range at my father’s 1961 Austin Healey Sprite, a car that was probably smaller than the oven that hit it. Mom and Dad were killed instantly.

I don’t know if things will ever be okay again. I lie to Jasmine and hug her tight, squeezing my eyes closed because, if I don’t, I’m going to start crying.

“We’ll need you to sign some paperwork…” says Miss Annoying.

“I’ll take care of that,” Nicole says.

“I’m afraid you can’t, she has to sign the papers.”

“Is this necessary?” Nicole’s tone is exasperated.

I look up. “I’ll sign. Whatever you need.” I stand, lifting Jasmine with me. Moments later, the woman shoves papers in front of me, including one indicating I’ll have to have a guardianship hearing in four weeks.

“Why is a hearing necessary?” I ask. “She’s my sister.”

The woman says, “Of course. It’s a formality, but the state has to formally make you her guardian. Don’t worry about it.”

Nicole mutters something unpleasant under her breath. I finish signing the papers, then wait until Linda goes off to make copies. Minutes later, we’re back in the sunlight and getting into Nicole’s cruiser.

Indecently normal (Zoe)

Nicole’s dad grew up in Boston, but ended up living and working in Western Massachusetts because that’s where he was able to find a job. Every once in a while the harsh nasal tones of Jamaica Plain come out in her speech. He’s a cop. She always wanted to be a cop. Thinking about him makes me feel warm—we spent much of our childhood at each other’s houses.

“The Lieutenant gave me a couple days off so I could help out, I’m switching some hours so I can cover the Big E clinic in a couple weeks anyway.” She drops the r in hours.

I shake my head. “The what?”

“Ah, well you know, basketball.”

“Right,” I say. I forget—even though Nicole was a giant nonconformist in high school, she inherited two things from her dad. She always wanted to be a cop, and she loves UMASS basketball. When she got out of the Army, she got to combine the two—she’s the newest member of the UMASS Amherst Police Department. Most campus police departments are tiny, but with a student population of more than 30,000, UMASS needs a larger one than most of the nearby towns.

As Nicole drives out of South Hadley Falls toward my parents’ house, my eyes keep drifting off the road and blurring. I haven’t been home yet—my flight got in at 9 am. Nicole picked me up at the airport, then we drove to get Jasmine. and I went straight to meet Nicole and pick up Jasmine. I don’t know what to expect when we get home.

Despite the balmy weather, I feel like February. Cold. Lifeless. I ignore the traffic on College Street until we approach Mount Holyoke College. The house is on the left.

It's a two-story Colonial with a wraparound porch and sagging foundations. Nine acres of horse pasture sprawl behind the neighboring properties. I have no idea where the horses are, or if anyone has taken care of them, or if they’re just on the property, hungry (or dead?). I don’t know if the house is locked, or if Jasmine has a key (I don’t have one) or anything much at all. I can see the house up ahead on the left, nestled in the shade of a stand of trees. The gravel driveway doesn’t look any worse than it did when I was on leave last January. I missed Christmas by a few weeks last year, but Mom and Dad made up for it, including cutting down a fresh tree and decorating it. When I walked in the house, exhausted from two solid days of travel, I saw the tree and almost burst into tears.

When my mother saw me, she did burst into tears.

I’m having trouble keeping it together today. It’s been months since I’ve been here, months since I’ve seen my parents, and I never expected to be coming home an orphan.

I don’t like the way the way word feels.

Nicole seems to sense my shift. She’s quiet as we approach the house. The left turn signal clicks as loud as helicopter blades when she slows down in front of the house. Traffic, oblivious traffic, flows by in the opposite direction. None of them know my parents are dead.

None of them know that I am going to have to figure out how to be a parent to an eight-year-old girl.

Nicole turns left. The tires hit the deep ruts of the driveway and a splash of mud flies away from the car. She comes to a stop behind my mother’s minivan and switches off the ignition. I can’t help but wonder if the accident would have been—not as bad—if they’d been driving the van. Or

anything

other than my father’s tiny hobby car.

We're blanketed in an uncomfortable and unpleasant silence. A bird chirps in the distance, and somewhere closer, a horse snorts.

I smell the pungent tang of a skunk. Not close, but close enough. You can often smell them in the area in the summer time.

I open the passenger door and slide out, my combat boots slipping half an inch into the mud. That’s okay. After today I won’t be wearing them much, unless it’s for working around the house and grounds.

As always, the house looks like it needs work. Mom and Dad loved the idea of fixing up an old house, but in practice it had always been more of a dream than practical reality. I love this old house. I also associate it with unfinished drywall, cracked and dry flooring, and drafty windows. Mom gardened sometimes, and often spent hours riding the horses, but Dad’s idea of enjoying the outdoors was sitting on the old rocker on the side porch or tinkering with his car. Staring at the house now, I’m left with an empty feeling. I can’t imagine the place without them.

I take a deep breath and listen again. I can hear the horses, for sure. As soon as we get into the house, I’ll walk over to the stable and check on them. In the meantime, I look down at Jasmine, who meets my eyes with an uncertain smile.

“You ready?”

She nods. But from the expression in her eyes, I don’t think she is. She’s an orphan too, and she’s never been in this house without our parents being alive. I pick her up and put my arms around her, and she squeezes her arms around my shoulders. Then I walk up the side stairs and onto the porch.

The gray paint on the porch deck is peeling underneath the rocking chairs. A glass, still half-full of sweet iced tea, sits on the table between the two rockers. It has to be sweet tea, because that’s all he ever drank. The tea has mold growing on the top. Dad must have left it when they went out.

I approach the side door and reach out to open it.

No luck. It’s locked. Of course. The keys are probably at the morgue, and I’m not going there, not with Jasmine. Maybe another day. In the meantime, I need to check the front and back doors and maybe the windows. Worse case, I can push one of the window-unit air conditioners in through the window and climb over it.

“Let me put you down. I gotta check the front door.”

I slide Jasmine to her feet, then walk to the front door. She hurries along beside me.

It’s locked. Damn it. I check under the mat and along the top of the door frame, but no luck.

“I’ll check the back,” Nicole says. She knows the way as well as I do—when we were in school, Nicole spent as much time in our home as she did in her own. In the meantime, I start checking for unlocked windows. Even if the windows aren't locked, they'll still be difficult to open. Many layers of paint combined with the heat of summer tend to seal windows shut.