Memoirs of Emma, lady Hamilton, the friend of Lord Nelson and the court of Naples; (19 page)

Read Memoirs of Emma, lady Hamilton, the friend of Lord Nelson and the court of Naples; Online

Authors: 1855-1933 Walter Sydney Sichel

Tags: #Hamilton, Emma, Lady, 1761?-1815, #Nelson, Horatio Nelson, Viscount, 1758-1805

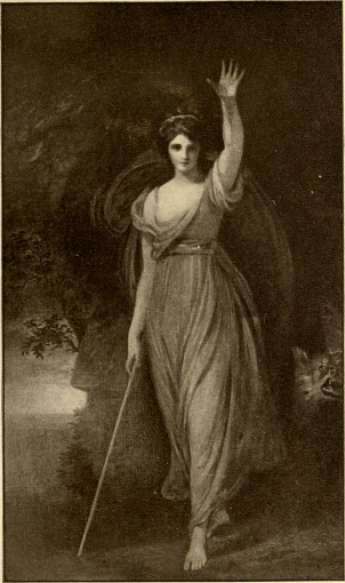

Lady Hamilton as Circe. From the original painting by George Romney.

which for a long time simmered in the political caldron. He was imprisoned in the fortress of Gaeta, to reappear, however, a few years later as a pardoned protege. Prince Caramanico, despatched after Sici-gniano's sad suicide to the Embassy in London, died before starting, with the usual suspicion of poison. The execution in the " Mercato Vecchio " of the cultivated Tommaso Amato, who was deprived even of supreme unction, lent its first horror to the notorious death-chamber of the " Capella della Vicaria," and was soon followed by that of sixty more Jacobins. The cause of " order and religion " was publicly pitted against these damnable heresies. Even communications with the self-styled " Patriots " were to be punished. It was decreed treason for more than ten to assemble, save by license. The judges, it is true, were bidden to be " conscientious in equity and justice," but three witnesses sufficed for the death-sentence. Apart from capital sentences, the castles and prisons were crammed with suspects, so much so that those of Brindisi were requisitioned. Massacres desolated Sicily; blood ran in the Neapolitan streets. Ferdinand, who had been amusing himself by lengthened law-suits with the Prince of Tarsia over a silk monopoly, called on the clergy to expose the " French errors "; and at Naples devotion and disaster ever trod closely on each other's heels. Three days of solemn prayer were once more decreed in the Metropolitan Church of St. Januarius. Both King and Queen were perpetually seen in devout attendance at the principal shrines. The pulpits preached " death to the French," and war against Jacobinism was declared religious. To be a " patriot " (an innocent fault in palmier days) was now sacrilege. A fresh eve of St. Bartholomew was feared. In a word, the methods of crushing rebellion and opinion

were eminently southern, but they were also a counter-Memoirs—Vol. 14—6

blast to equal barbarities in the north. Save for the sansculottes and their propaganda, Naples would have escaped the fever and remained a drowsy castle of contented indolence.

While, as queen, Maria Carolina cowed the city, as woman she was demented by Buonaparte's Italian victories. Naples, alone of all Italy, still defied him. The Neapolitan royalties—to their honour—sacrificed fortune and jewels to dare the new Alexander. At the same time, they called on both nobles and ecclesiastics to emulate their public spirit, and thereby unconsciously did much to hasten the " patriot " insurrection. One hundred and three thousand ducats were demanded from the town, one hundred and twenty thousand from the nobles; church property was alienated. Everything was seized for the common cause. The news of Nelson's heroism and the English triumph in Corsica was received with rapture. And the Neapolitan troops on this occasion shamed the general cowardice. By 1795 Prince Moliterno was acclaimed a national hero; the courage of General Cuto's three regiments in the Tyrol raised the Neapolitan name, while Mantua and Rome showed the white feather and necessitated the onerous peace of Brescia.

It may now be guessed what agitated the Queen's bosom as day by day she sat down to pen her French missives to Emma, and what were the feelings naturally instilled in Emma by Hamilton, Nelson's letters, and the Queen. The Jacobin cause was the prime pest of Europe, to be crushed at all costs; Napoleon, an impudent upstart and usurper; the Neapolitan rebels, monsters of ingratitude and treachery. All these convictions were as binding as articles of faith. Emma's own heart was tender to a fault. She detested bloodshed and liked to use her influence for mercy, as, to do her bare justice, was then the Queen's instinct, after

the first spasm had passed. In Emma's eyes the Queen herself, so kind and good at home, so sincere and friendly, was " adorable." She could do no wrong. The past peccadilloes of this baffling woman, contrasting with her present domesticity, seemed to her, even if she believed them, merely a royal prerogative. She was—as Emma assured Greville in a letter congratulating him on his new vice-chamberlainship, " Everything one can wish—the best mother, wife, and freind in the world. I live constantly with her, and have done intimately so for 2 years, and I never have in all that time seen anything but goodness and sincerity in her, and if ever you hear any lyes about her, contradict them, and if you shou'd see a cursed book written by a vile French dog, with her character in it, don't believe one word." Hours passed with her were " enchantment." " No person can be so charming as the Queen. If I was her daughter she could not be kinder to me, and I love her with my whole soul." As she grew more influential on the stirring scene she caught and exaggerated her royal friend's effusiveness. " Oh that everyone," is her endorsement on a letter, " could know her as I do, they would esteem her as I do from my soul. May every good attend her and hers." Thus Ruth, of Naomi. From such a friend impartiality was no more to be expected than from such enemies as the " vile French dogs."

The Queen's correspondence 1 with Emma opens earlier with a touching note about the fate of the poor Dauphin; a sweet little portrait still remains under its cover. This innocent child, she wrote, implores a sig-

1 Most of her letters of this and the next five years are transcribed from the various Egerton MS. by R. Palumbo in his Maria Carolina and Emma Hamilton, which to much valuable material adds some of the old rumours about her earlier and later life.

nal vengeance for the massacre of his parents before the Eternal Throne. His afflictions " have renewed wounds that will never heal." In January, 1794, a fete was given by the Hamiltons to Prince Augustus. It was a golden occasion for fanning the English fever, which by now had spread throughout the loyalist ranks. The Queen's letter of that afternoon begged the hostess to tell her company " God save great George our King," rejoiced over the Anglo-Sicilian alliance, and sent her compliments to all the English present. In the following June she exulted over George's speech to Parliament renewing the war. She longed for English news from Toulon. At his fete two years later, she was to protest that she loved the British prince as a son. She was perpetually anxious about Emma's health and prescribing remedies. As for her own " old health," it was not worth her young friend's disquietude. When Sir William lay at death's door she bade her " put confidence in God, who never forsakes those who trust in Him," and count on the " sincere friendship" of her " attached friend." Emma's performances she applauded to the skies, especially that of " Nina," which had been Romney's favourite.

In one of her constant billets she tenderly inquired after " ce cher aimable bienfaisant eveque " —the flippant but kindly worldling and " Right Reverend Father in God " (as Beckford terms him) Lord Bristol, Bishop of Derry. Of this odd wit, erratic vagrant and sentimental scapegrace, so typical of a century that included both Horace Walpole and Laurence Sterne—a veritable Gallio-in-gaiters, with his whimsical projects for endless improvements, his connoisseurship, his restlessness, his real pluck and independence, we have already caught glimpses in eccentric attire at Caserta. One of his queerest features was the blended care

and carelessness both of money and family. Attached to his devoted and economical daughter Louisa, he quarrelled with his son for not marrying an heiress. His bitterest reproach against his old wife was that she disbelieved " in the current coin of the realm." Lady Hamilton thus at this time described him to Greville: " He is very fond of me, and very kind. He is very entertaining and dashes at everything. Nor does he mind King and Queen when he is inclined to shew his talents." The French victories were soon to be fatal to the esprit moqueur, and to cool his volatile impatience for some eighteen months within the clammy walls of a Milanese fortress. Besides his autographs in the Morrison Collection, and two now belonging to the writer, a few letters from him to Emma exist in that surreptitious edition of the pilfered Nelson Letters which, in 1814, were to add one more drop to her cup of bitterness. They all show that he purveyed information, both serious and scandalous, through Emma to the Queen. They stamp the intriguer, the patriot, and the friend. The first seems written among the embroilments of 1793.

The sale and purchase of antiquities absorbed him like Sir William; unlike the Ambassador, he never shirked labour, but rather meddled officiously with the departments over which his leisurely friend had been up to now so disposed to loiter. In 1793 he is to be found spying on the spies who misled " the dear, dear Queen." At the opening, too, of 1794, he forwards Venetian secrets to be communicated " a la premiere des femmes, cette tnaltresse femme." " I have been in bed," he adds, " these four weeks with what is called a flying gout, but were it such it would be gone long ago, and it hovers round me like a ghost round its sepulchre." In 1795 again the nomad was at Berlin routing out State-secrets. The date of the following

must be that of the shameful Austrian treaties in 1797 which succeeded the galling peace of Brescia.

" MY EVER DEAREST LADY HAMILTON, 1 should

certainly have made this Sunday an holy day to me, and have taken a Sabbath day's journey to Caserta, had not poor Mr. Lovel been confined to his bed above three days with a fever. To-day it is departed; to-morrow Dr. Nudi has secured us from its resurrection; and after to-morrow, I hope, virtue will be its own reward. . . . All public and private accounts agree in the immediate prospect of a general peace. It will make a delicious foreground in the picture of the new year; many of which I wish, from the top, bottom, and centre of my heart, to the incomparable Emma— qnella senza paragone." The next snatch is worth quoting for its humour:—" I went down to your opera-box two minutes after you left; and should have seen you on the morning of your departure—but was detained in the arms of Murphy, as Lady Eden expresses it, and was too late. You say nothing of the adorable Queen; I hope she has not forgot me. ... I veritably deem her the very best edition of a woman I ever saw—I mean of such as are not in folio. . . . My duties obstruct my pleasure. ... You see, I am but the second letter of your alphabet, though you are the first of mine."

A last extract, penned a few months after his liberation, must complete this vignette:—" I know not, dearest Emma, whether friend Sir William has been able to obtain my passport or not; but this I know—that if they have refused it, they are damned fools for their pains: for never was a Malta orange better worth squeezing or sucking; and if they leave me to die, without a tombstone over me to tell the contents— taut pis pour eux. In the meantime, I will frankly confess to you that my health most seriously and urgently re-

quires the balmy air of dear Naples, and the more balmy atmosphere of those I love, arid who love me; and that I shall forego rriy garret with more regret than most people of my silly rank in society forego a palace or a drawing-room." He then sketched his tour on horseback to " that unexplored region Dal-matia "; he described Spalato as " a modern city built within the precincts of an ancient palace." Spalato reminded him of Diocletian, the " wise sovereigti who quitted the sceptre of an architect's rule," and the two together, of a new project for a " packet-boat in these perilous times between Spalato and Manfredonia."

The serious debut of Emma as " Stateswoman " (in the sense of England's spokeswoman at Naples) chimes with the episode of the King of Spain's secret letters heralding and announcing his rupture with the anti-French alliance during 1795 and 1796. But before dealing with that crisis, I may be pardoned for glancing at one more picturesque figure among Emma's surroundings—that of Wilhelmina, Countess of Lich-tenau.

She was nobly born and bred; but in girlhood, under a broken promise, it would seem, of morganatic marriage, had become mistress and intellectual companion of Frederick, King of Prussia—a tie countenanced by her mother. Political intrigue drove her from Berlin to Italy, as it afterwards involved her in despair and ruin. She was cultivated, artistic, sensitive, and unhappy. She became the honoured correspondent of many distinguished statesmen and authors. Lavater and Arthur Paget were her firm friends, as also the luckless Alexandre Sauveur, already noticed in his " hermitage" on Mount Vesuvius. Lord Bristol, naturally, knelt at her shrine. In her Memoires she frankly admits that she (like Emma) was vain; but maintains that all women are so by birthright. Lovel,

the parson friend of the Bishop of Derry, used to sign himself her " brother by adoption," and address her as " a very dear sister "; Paget corresponded with her as " dear Wilhelmina." Throughout 1795 she was at Naples, where her cicisbeo was the handsome Chevalier de Saxe, afterwards killed in a duel with the Russian M. Saboff. A letter from him towards the close of this year of Neapolitan enthusiasm for the English, when the Elliots among others were praising and applauding Emma to the skies, describes the great ball given by Lady Plymouth in celebration of Prince Augustus's birthday. The supper was one of enthusiasm and " God save the King." " They drank," he chronicles, "a I'Anglaise: the toasts were noisy, and the healths of others were so flattered as to derange our own." Sir William was constantly begging of her to forward the sale of his collections at the Russian capital; nor was tea, now fashionable at court, the least agent for English interests. Emma herself had become the " fair tea-maker " of the Chiaja instead of, as once, of Edgware Row, and Mrs. Cadogan too held her own tea-parties. Emma often corresponded with the beautiful Countess, and one of her letters of this period, not here transcribed, supplies evidence of what kind of French she had learned to write by a period when she had mastered not only Neapolitan patois but Spanish and Italian. At the troublous outset of 1796 Wilhelmina quitted Italy never to return.

These characters are scarcely edifying. The scoffing Bishop, the frail Countess, however, were a typical outcome of sincere reaction against hollow and hypocritical observance. There was nothing diabolical about them. The virtues that they professed, they practised; their faults, those of free thinkers and free livers, do not differentiate them from their contemporaries. It is surely remarkable that these, and such

as these, paved the way for Nelson's vindication of Great Britain in the Mediterranean, far more than the train of decent frivolity and formal virtue that did nothing without distinction. High Bohemia has always wielded some power in the world. Far more was it a force when the French Revolution threatened the very foundations of society, and opened up avenues to every sort of adventure and adventurer.

Emma has already been found twice acquainting Greville of her new metier as politician. Her present circumstances and influence over the Queen may be gauged independently by a letter from her husband to his nephew from Caserta of November, which has only recently passed into the national collection:—

". . . Here we are as usual for the winter hunting and shooting season, and Emma is not at all displeased to retire with me at times from the great world, altho' no one is better received when she chuses to go into it. The Queen of Naples seems to have great pleasure in her society. She sends for her generally three or four times a week. ... In fact, all goes well chez nous. [He is taking more exercise.] . . . I have not neglected of my duty, and flatter myself that I must be approved of at home for some real services which my particular situation at this court has enabled me to render to our Ministry. I have at least the satisfaction of feeling that I have done all in my power, altho' at the expense of my own health and fortune." This last sentence points to the political situation, and Emma's assistance in the episode of the King of Spain's letters; for not one, but a whole series were involved.

These letters, from 1795 to 1796, were the secret channels by which Ferdinand was made aware first of his brother's intention to desert the Alliance, and, in the next year, to join the enemy.

In touching the effects and causes of an event so critical, Emma's pretensions to a part in its discovery must be discussed also. Their consideration, interrupting the sequence of our narrative, will not affect its movement. It is no dry recital, for it concerns events and character.

From 1795 to the opening of 1797 the league against Napoleon, as thrones and principalities one by one tottered before him, was faced by rising republics and defecting allies. In vain were Wurmser and the Neapolitan troops to rajly the Romagna. In vain did Nelson recount to the Hamiltons Hood's and Hotham's successes along the Jtaliajn coast. Acton's own letters of about this period complain of the Austrian delays and suspicions. Prussia estranged herself from the banded powers. England herself was, for a moment, ready to throw up the sponge. In 1795, so great was the popular fear of conflict, that prints in every London shop window represented the blessings of peace and the horrors of war. Even in the October of 1796 Nelson told the Hamiltons, with a wrathful sigh, " We have a narrow-minded party to work against, but I feel above it." - And writing from Bastia in December, 1796, he was again indignant at the orders for the evacuation of the Mediterranean, which plunged the Queen in despair. " Till this time," commented the true patriot, " it has been usual for the allies of England to fall from her, but till now she never was known to desert her friends whilst she had the power of supporting them."