Memoirs of Emma, lady Hamilton, the friend of Lord Nelson and the court of Naples; (51 page)

Read Memoirs of Emma, lady Hamilton, the friend of Lord Nelson and the court of Naples; Online

Authors: 1855-1933 Walter Sydney Sichel

Tags: #Hamilton, Emma, Lady, 1761?-1815, #Nelson, Horatio Nelson, Viscount, 1758-1805

Nelson, was that its discussion might compromise the Neapolitan Queen. This, then, was the end of the royal gratitude so long and lavishly professed. When Emma in this year besought her, not for herself, but for Mrs. Grafer (then on the eve of return to Palermo), she told Greville that she had adjured her to redeem her pledge of a pension to their friend " by the love she bears, or once bore, to Emma," as well as " by the sacred memory of Nelson." If the Queen was at this time in such straits as precluded her from a pecuniary grant once promised to the dependant, she might still have exerted herself for her dearest friend. But " Out of sight, out of mind." In despair, while Rose returned to his barren task of doing little elaborately, Emma betook herself to Lord St. Vincent. If her importunities could effect nothing with the gods above, she would entreat one of them below. Perhaps Nelson's old ally could melt the obdurate ministers into some regard for Nelson's latest prayers; perhaps through him she might draw a drop, if only of bitterness, with her Danaid bucket from that dreary official well.

She conjures him by the " tender recollection " of his love for Nelson to help the hope reawakened in her " after so many years of anxiety and cruel disappointment," that some heed may be paid to the dying wishes of " our immortal and incomparable hero," for the reward of those " public services of importance " which it was her " pride as well as duty to perform." She will not harrow him by detailing " the various vicissitudes" of her " hapless" fortunes since the fatal day when " Nelson bequeathed herself and his infant daughter, expressly left under her guardianship, to the munificent protection of our Sovereign and the nation." She will not arouse his resentment " by reciting the many petty artifices, mean machinations,

and basely deceptive tenders of friendship" which hitherto have thwarted her. She reminds him that he knows what she did, because to her and her husband's endeavours she had been indebted for his friendship. The widow of Lock, the Palermo Consul, had an immediate pension assigned of £800 a year, while Mr. Fox's natural daughter, Miss Willoughby, obtained one of £300. Might not the widow of the King's foster-brother, an Ambassador so distinguished, hope for some recognition of what she had really done, and what Nelson had counted on being conceded?

At the same time both she and Rose besought Lord Abercorn, who interested himself warmly in her favour. In Rose's letter occurs an important passage, to the effect that Nelson on his last return home had, through him, forwarded to Pitt a solemn assurance that it was through Emma's " exclusive interposition that he had obtained provisions and water for the English ships at Syracuse, in the summer of 1798, by which he was enabled to return to Egypt in quest of the enemy's fleet "; and also that Pitt himself, while staying with him at Cuffnells, had " listened favourably " to his representations. Rose had previously assured Lady Hamilton that he was convinced of the " justice of her pretensions," to which she " was entitled both on principle and policy."

And not long afterwards, when, as we shall shortly see, kind friends came privately to her succour, she forwarded another long memorial to Rose, in whose Diaries it is comprised, clearly detailing both services and misadventures. " This want of success," she repeats, and with truth, " has been more unfortunate for me, as I have incurred very heavy expenses in completing what Lord Nelson had left unfinished at Mer-ton, and I have found it impossible to sell the place." She might have added that Nelson entreated her not

to spend one penny of income on the contracts; he never doubted that this cost at least the nation would defray. " From these circumstances," she resumes, " I have been reduced to a situation the most painful and distressing that can be conceived, and should have been actually confined in prison, if a few friends from attachment to the memory of Lord Nelson had not interfered to prevent it, under whose kind protection alone I am enabled to exist. My case is plain and simple. I rendered a service of the utmost importance to my country, attested in the clearest and most undeniable manner possible, and I have received no reward, although justice was claimed for me by the hero who lost his life in the performance of his duty. ... If I had bargained for a reward beforehand, there can be no doubt but that it would have been given to me, and liberally. I hoped then not to want it. I do now stand in the utmost need of it, and surely it will not be refused to me. ... I anxiously implore that my claims may not be rejected without consideration, and that my forbearance to urge them earlier may not be objected to me, because in the lifetime of Sir William Hamilton I should not have thought of even mentioning them, nor indeed after his death, if I had been left in a less comparatively destitute state."

Yet the latter was the excuse continuously urged by successive Governments. Both Rose and Canning, more than once, admitted the justice of her claims, and even Grenville seems by implication not to have denied it. Rose always avowed his promise to Nelson at his " last parting from him " to do his best, and he did it. But he well knew that the real obstacle lay not in doubt, or in lapse of time, or in the quibble of how and from what fund it would be possible to satisfy her claims, but solely in the royal disinclination to favour one whom the King's foster-brother had mar-

ried against his will, and whose early antecedents, and later connection with Nelson, alike scandalised him. The objections raised were always technical and parliamentary, and never touched the substantial point of justice at all. The sum named— £6000 or £7000—would have been a bagatelle in view of the party jobbing then universally prevalent; and no attentive peruser of the whole correspondence from 1803-1813 can fail to grasp that each successive minister—one generously, another grudgingly—at least never disputed her claims even while he refused them. It was not their justice, but justice itself that was denied, and the importunate widow was left pleading before the unjust judge who had more advantageous claimants to content. Pitt's death, in January, 1806, was undoubtedly a great blow to Emma's hopes. During his last illness she must often have watched that white house at Putney with the keenest anxiety. So early as the beginning of 1805, Lord Melville, whom Nelson had asked to bestir himself on Emma's behalf during his absence, told Davison that he had spoken to Pitt personally about " the propriety of a pension of £500" for her. Melville himself spoke " very handsomely " both of her and her " services." Pitt, if he had survived more than a year and had been quit of Lord Grenville, might have risked the royal disfavour, as in weightier concerns he never shrank from doing. The luckless Emma sank apparently between the two stools of social propriety and official convenience, while the hope against hope, that no disillusionment could extinguish, constantly made her the victim of her anticipations.

For a moment a purchaser willing to give £13,000 for Merton had been almost secured. But debts and fears hung around her neck like millstones. They interrupted her correspondence and sapped her health,

now in serious danger. By June, 1808, she told her surgeon, Heaviside, that she was so " low and comfortless " that nothing did her good. Her heart was so " oppressed " that " God only knows " when that will mend,—" perhaps only in heaven." He had " saved " her life. He was " like unto her a father, a good brother." In vain she supplicated " Old Q." to purchase Merton and she would live on what remained : he had named her in his will, and that sufficed. With her staunch servant Nanny, and her faithful " old Dame Francis," who attended her to the end she and Horatia retired to Richmond, where for a space the Duke allowed her to occupy Heron Court, though this too was later on to be exchanged for a small house in the Bridge Road. She herself drew up a will, bequeathing what still was hers to her mother for her life, and afterwards to " Nelson's daughter," with many endearments, and expressing the perhaps impudent request that possibly she might be permitted to rest near Nelson in St. Paul's, but otherwise she desired to rest near her " dear mother." She begged Rose to act as her executor, and she called on him, the Duke, the Prince, and " any administration that has hearts and feelings," to support and cherish Horatia.

All proved unavailing, and she resigned herself to the inevitable liquidation. After a visit to the Bol-tons in October, she returned to arrange her affairs in November.

A committee of warm friends had taken them in hand. Many of them had powerful city connectiohs. Sir John Perring was chairman of a meeting convened in his house at the close of November. His chief associates were Goldsmid, Davison, Barclay, and Lavie, a solicitor of the highest standing, and there were five other gentlemen of repute.

A full statement had been drawn up. Her assets

amounted to £17,500, " taken at a very low rate," and independent of her annuities under the two wills and her " claim on the Government," which they still put to the credit side. Her private debts, of which a great part seems to have been on account of the Mer-ton improvements, amounted to £8,000, but there were also exorbitant demands on the part of money-lenders, who had made advances on the terms of receiving " annuities." To satisfy these, £10,000 were required.

Everything possible was managed. All her assets, including the prosecution of those hopeless claims, were vested in the committee as trustees, and they were realised to advantage. Goldsmid himself purchased Merton. £3700 were meanwhile subscribed in advance to pay off her private indebtedness.

At this juncture Greville reappears unexpectedly upon the scene. In her sore distress he thawed towards one whom his iciest reserve and most pettifogging avarice had never chilled. He had evidently asked her to call, though he never seems to have offered assistance. She answered, in a letter far more concerning her friend Mrs. Grafer's affairs than her own, that an interview with her " trustees " must, alas ! prevent her:—" I will call soon to see you, and inform you of my present prospect of Happiness at a moment of Desperation"; you who, she adds, "I thought neglected me, Goldsmid and my city friends came forward, and they have rescued me from Destruction, Destruction brought on by Earl Nelson's having thrown on me the Bills for finishing Merton, by his having secreted the Codicil of Dying Nelson, who attested in his dying moments that I had well served my country. All these things and papers . . . I have laid before my Trustees. They are paying my debts. I live in retirement, and the City are going to bring forward my claims. . . . Nothing, no power

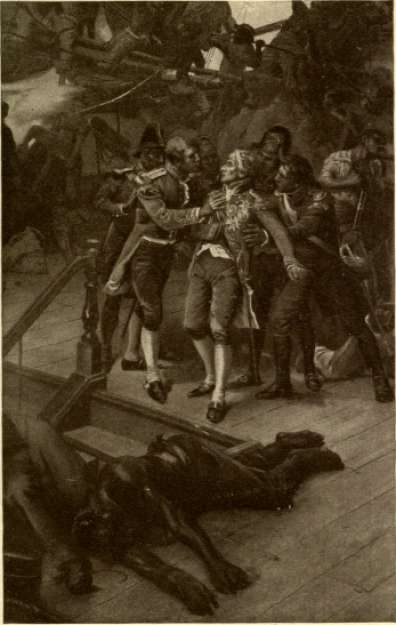

The death of Admiral Nelson at the battle of Trafalgar. "Thank God, I have done my duty."

From the Painting by W. H. Overend.

EMMA, LADY HAMILTON

on earth shall make me deviate from my present system" she concludes, using the very word which Greville used concerning his methods with womankind in the first letter which she ever received from him. Goldsmid had been an " angel"; friends were so kind that she scarcely missed her carriage and horses.

Emma had every reason to be grateful. She was clear of debt. She could still retain the valuables that were out of Merton. With Horatia's settlement, she could count on her old revenue when the " annuities " had been discharged. Somehow they never were, and they again figure largely during her last debacle. The mysteries of her entanglements baffle discovery; so does her sanguine improvidence which, to the end, alternated with deep depression. In a few years she and Horatia, like Hagar and Ishmael, were to go forth into the wilderness; but even then she was still buoyed up with this mirage of an oasis in her tantalising desert.

Relieved for the moment, she resumed the tenor of her way at Richmond. She frequented concerts, and sometimes dances, in the fashionable set of the Duke and the Abercorns. In June, 1809, Lord Northwick begged her to come to the Harrow speeches, and afterwards meet a few " old Neapolitan friends " and her life-long friend the Duke of Sussex at " a fete in his house." The fame of Horatia's accomplishments added the zest of curiosity. All were eager to meet the " interesting eleve whom Lady Hamilton has brought up " with every grace and every charm. The Duke of Sussex looked forward to the encounter with pleasure; Emma had not yet lost her empire over the hearts of men. Of this invitation Emma took advantage to do a thoughtful kindness for an unhappy bride who had just married the composer Francesco

Memoirs—Vol. 14—15

Bianchi. Twelve days earlier she had tried apparently to heal the breach between them.

The Bohemians, therefore, were always with her. She continued to receive the Italian singers as well as their patrons; she still saw Mrs. Denis and Mrs. Bil-lington, whose brutal husband, Filisan, was now threatening her from Paris; while Mrs. Grafer, on the very eve of return to Italy, continued to beset her with importunities. Nor did her old friends, naval, musical, and literary, spare the largeness of her hospitality or the narrowness of her purse.

But, in addition to these diversions, she still overtasked herself with Horatia's education—so much so, that Mrs. Bolton wrote beseeching her to desist. Sarah Connor had now transferred her services to the Nelson family, and Emma eventually took the musical but far less literate Cecilia for Horatia's governess.