Mendel's Dwarf (30 page)

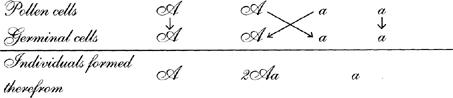

“The result of fertilization can be visualized by writing the designations for associated germinal and pollen cells in the form of fractions, pollen cells above the line, germinal cells below. In this case one obtains—slide, please—”

There are mutterings in the darkness. Do they signify discontent? He casts sharp shadows across the wall and into the future, this small stout friar with the obtuse manner and the abstruse jokes. This is a moment like few others in the history of science and his audience is laboring along in his wake.

“What I show here represents the

average

course of self-fertilization of hybrids when two differing characters are associated in them. In individual flowers and individual plants, however, the ratio in which the members of the series are formed may be subject to not-insignificant variations. Next slide, please. Here you may see the series for hybrids in which two kinds of differing characters are associated. In fertilization every pollen cell unites, on average, equally often with each form of germinal cell; thus each of the four pollen cells

AB

unites once with each of the germinal forms AB,

Ab, aB, ab:

”

Can you wonder that a great silence fell in the room, the silence of incomprehension, of indifference, of boredom? Can you wonder that the applause at the end was thin and the congratulations lukewarm? There were polite questions and a little discussion. But as the members of the Brünn Society for Natural Science dispersed into the cold night, there was a vague sense of embarrassment, a feeling that they had been called out in the cold evening on a fool’s errand. They had come to see about plants and hybrids; they had got mathematics.

“But this is not even hybridization,” someone was heard to remark, a man who had read Darwin and considered himself as well up in the understanding of such things as anyone in the society. “Hybridization is the crossing of separate species. This is nothing more than crossing different varieties.” He pronounced the word

varieties

with contempt, as though he had said

gypsy

or

Jew

. “What is the point of worrying about whether you have green or yellow seeds? What matters is whether species themselves are mutable or whether they are distinct …”

“And what does

mathematics

have to do with biology?” complained another. “In the whole of Gärtner’s work, or Darwin’s work, come to that, there isn’t a single mathematical formula …”

Wise nods, stern agreement. Not anger, but disappointment and frustration, coupled with a sense of resentment at a wasted evening.

“It was fascinating, Gregor,” Frau Rotwang assured Mendel. She was waiting in the entrance hall as the audience left. She used his Christian name alone. She was solicitous and concerned.

“Do you think they saw it all?” He polished his spectacles and then carefully fitted them on his face. “Do you think it was too much for them?”

“It was fine.” She laid a consoling hand on his arm. She hadn’t understood a word.

And what have I achieved with my dwarfs? I can hear you asking the question. Never mind the personal crises. What has Doctor Benedict Lambert of the Royal Institute for Genetics, remote ancestor of this Gregor Mendel, what has

he

discovered?

The audience waits, shuffling papers, coughing and muttering. Those noises, minimal enough, fade away into an expectant hush as the side door opens and Benedict Lambert steps onto the stage. All eyes watch the diminutive figure as he lays out his papers and his overhead projector transparencies. He glances up at the tiers of expectant faces almost in surprise, almost as though he had come in here for some other purpose and had not expected this crowd.

“Good morning,” he says conversationally. Then he slips his watch from his wrist and lays it carefully on the lecture bench (a complete affectation this: there are wall clocks sited conspicuously around the theater) before looking back at the audience. The director is there, of course, seated front center: James Histone, CBE (when, oh when, will it be

Sir

James?). Like a portrayal of the Almighty in a medieval fresco he is surrounded by an aureole of lesser beings—the project directors, the postdocs, the graduate students, and finally, mere peasants on the outer edges, the undergraduates. And somehow Miss Jean Piercey is there, over on the left-hand side, five rows back. Her phenotype has changed. She looks different; but her mere appearance still brings a jolt to Benedict Lambert’s equanimity. She smiles.

He takes a deep, calming breath, and begins:

“The most common form of dwarfism in humans is achondroplasia. This condition, characterized by disproportionate short stature, proximal shortening of the extremities, macrocephaly, midface hypoplasia, bowing of the lower limbs, and exaggerated lumbar lordosis, is inherited as an autosomal dominant character with 100-percent penetrance. Therefore there are no

carriers of the condition. To possess one such gene is to own the deformity.”

There is a great silence.

“To possess two ACH genes, one inherited from each dwarf parent, to be homozygous for the condition, is to die in infancy. As a consequence of this, more than 90 percent of cases are sporadic—that is, they are the result of chance mutation. Increased paternal age at the time of conception appears to be a significant factor, suggesting that mutations of paternal origin are involved. Furthermore, with an incidence of approximately one per fifteen thousand live births it is one of the more common

de novo

Mendelian disorders, which in itself provides sufficient reason for attempting to identify its cause.”

A pause; an ironical smile; just a touch of bitterness: “The more astute among you may be able to work out another motive.”

The director laughs. Thus sanctioned from the center, amusement spreads toward the periphery of the theater like ripples in a pond from a thrown stone. The celebrated Benedict Lambert has done it again: he has laughed to scorn the very gene that has wreaked havoc with his own body. Captain Ahab, perhaps? We have both been mutilated, certainly. But Ahab pursued a vast beast, a phenotypic complex of muscle and bone and blubber and nerve, while I pursue a mere molecule, a fragment of a molecule, a sequence of chemical bases that the human eye will never see. Yet both of us pursue our obsessions with a measure of hatred and a measure of love. Even Jean smiles, although her smile has more than a touch of irony to it.

“Over the last few years I and my team.”—a nod here in the right direction—“have collected a number of pedigrees associated with this condition, and we believe that we have finally localized and identified the gene.”

A rush of excitement throughout the theater, although they knew it already. That, after all, is

why

they are here. All this has something of the drama of a well-known play: you know the plot well enough, but at the climactic moment, there is still the thrill

of catharsis. Lady Macbeth still terrifies; Uncle Vanya still evokes empathy; the Master Builder still climbs his tower to frighten the watchers below. I point to a chromosome map, striped like a barber’s pole, flung up onto the screen behind me: “Multipoint linkage analysis gives us a location for the achondroplasia gene in the short arm of chromosome 4, distal to the gene for Huntington’s disease. The ACH location is close to the locus of the

IDUA

gene, and indeed initially

IDUA

was considered a candidate gene for the condition. However,

IUDA

mutations are known already to cause a number of symptoms that do not resemble ACH in any way …”

There is silence, anticipation. The surface of the ocean stirs and heaves. Will the great white whale emerge and be revealed in all its power?

“… and at least four other genes in the same area presented themselves as alternatives. One of these was the gene for fibroblast-growth-factor receptor 3. The fact that this gene is expressed in cartilage-forming cells in the mouse made it seem likely to be the one we sought. Subsequent sequencing of this gene has confirmed this suspicion …”

We have read the texts. Like latter-day Bible scholars, like exegetes, we have read the words of the scroll of life. I give you a message from this enigmatic, molecular world:

5′ … GGC ATC CTC AGC TAC GGG GTG GGC TTC TTC CTG … 3′

and this, the cry of the beast:

5′ … GGC ATC CTC AGC TAC AGG GTG GGC TTC TTC CTG … 3′

That is it.

1

Can you spot the difference? In all the thousands of letters that make up the message, just one change spells disaster.

G to A, a simple transition at nucleotide 1138 of the

FGFR3

gene. Guanine becomes adenine. It is a trivial thing in the infinite and infinitesimal machinations of the human genome. It is an error in a single base pair, an error in the transcription of a single letter. There are 3.3 × 10

9

base pairs in the human genome. So, one mistake in thirty-three billion letters and we (B. Lambert et al.) have focused in on that single letter error. It seems like textual analysis gone mad. But you may rest assured that there is nothing trivial about this error, this one-in-thirty-three-billion chance (how Great-great-great-uncle Gregor would have loved that!). No, this footling mistake means that during the synthesis of a particular protein an amino acid called arginine is slipped into one position that ought to be occupied by a different amino acid called glycine. To be precise, this occurs in the transmembrane domain of the protein, the part of the molecule that fits through the cell membrane. The protein is fibroblast-growth-factor receptor 3.