Mendel's Dwarf (4 page)

I recall one of the questions, just one: If it takes three minutes to boil an egg, how long does it take to boil one hundred eggs?

The answer, gentle reader, is

three minutes

. Anything else is wrong. At the time, sitting in an anonymous classroom of the local grammar school, stared at by the dozen or so children who, like me, were sitting the exam, I wanted to write,

It all depends

… But I was too intelligent to do anything stupid like that.

Three minutes

.

“At least he’s got something going for him, poor little chap,” one of my mother’s friends said. I overheard them talking shortly after news of my success had come through. “At least he’s got a brain in his head. Where did he get that from, I wonder? Was it his father? I expect it was. Although you can’t tell, can you?” My mother was at the sewing machine, frowning with concentration as she made some kind of shirt that would fit me, accommodate my all-but-normal trunk and my shrunken arms. Whenever she was at home, whenever she wasn’t cooking or doing the dishes, she seemed to be sewing clothes for me. It is impossible to buy clothes, you see. The industry doesn’t take into account people of my proportions.

At least he’s got a brain in his head

. Even then I wasn’t so sure that was much of a consolation. But I passed the examination and was admitted to the grammar school.

At my grammar school, biology was taught in a classroom like all the others. There was a blackboard and a raised podium at one end, and rows of sloping desks facing it in dutiful attention. Mendel himself would have recognized the kind of place. Elsewhere in the school there were proper laboratories for physics and chemistry, but biology was an afterthought, consigned to a room that was fit for dictation, for sitting and listening and taking notes. There was an atmosphere of lassitude about the place, a sensation that nothing much would ever happen there. A poster on the wall showed the internal organs

of the human body in lurid and unlikely color. It was a prudish, sexless picture, and someone had tried to scribble in genitals where none had previously existed. The attempt had been rubbed out, but the crude lines were still risible like the scars from some dreadful operation. Below the poster was a bench with a row of dusty test tubes containing

Tradescantia

cuttings, the debris of some halfhearted demonstration that had been set up weeks before and then forgotten. There were microscopes, but they were locked away in some cupboard and marked for senior pupils only.

I clambered with difficulty onto a chair. The class watched and whispered. The biology teacher, a Mr. Perkins, coughed impatiently as though it were my fault that I was late, my fault that I was an object of curiosity, that I was what I was and am. “Gregor Mendel was an Austrian monk,” he informed us once quiet had fallen. He paid scant attention to matters of fact. “The monastery was miles away from anywhere. No one knew about him and his work, and he knew nothing about what was going on in the scientific world of his time, but despite all these disadvantages, he started the whole science of genetics. There’s a lesson for you. You don’t need expensive laboratories and all the equipment. You just need determination and concentration. Stop talking, Dawkins. You never stop talking, boy, and you never have anything worth saying. You will find a photograph of Mendel on page one hundred and forty-five of your textbook. Look at it carefully and reflect on the fact that it is the likeness of a man with more brains in his little finger than you have in the whole of your cranium. But photographs won’t help you pass your exams, will they, Jones? Not if you don’t pay attention and don’t learn anything and spend all your time fiddling.”

I turned the pages. From page 145 a face looked out of the nineteenth century into the twentieth with a faint and enigmatic smile, as though he knew what was in store. I held my secret to my chest, like a cardplayer with a magnificent hand.

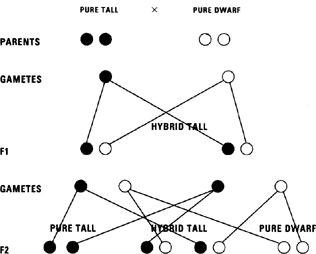

“Below the picture you may see one of his crosses,” Mr. Perkins said. “Study it with care, Jones.”

“This is the most famous of his experiments. Mendel took two strains of garden pea—”

“Please, sir, how do you strain a pea, sir?”

“Shut up, boy.”

“Dawkins strains while having a pee. Is that anything to do with it, sir?”

“Detention, boy! You are in detention. One of the strains was tall and the other was dwarf …”

“Is a dwarf like Lambert, sir?”

The racket of laughter stopped. Mr. Perkins reddened. “That’s enough of that, boy.”

“But is it, sir?”

“Enough, I said. Now I want to explain what Mendel discovered. You will open your notebooks and take down this dictation …”

And then I played my hand. “Please sir, he’s my uncle. I mean

great-uncle. Great-great-great-uncle. That’s what Uncle Harry told me.”

There was a terrible silence. Someone giggled. “Don’t be foolish, child,” Mr. Perkins said.

“He is, sir.”

The giggling spread, grew, metamorphosed into laughter.

“But he

is

, sir. Uncle Hans. Great-great-great-uncle Hans Gregor.”

The laughter rocked and swayed around the room, around the small focus of my body and around the wreckage of my absurd boast. Great-great-great-uncle. “Great-great-great,” they called. “Great-great-great! Great-great-great!”

“Shut up!

There will be silence!

”

The laughter died away to mere contempt. “You will open your notebooks,” Mr. Perkins repeated in menacing tones, “and take down this dictation …”

After the lesson they confronted me in the playground and taunted me with Uncle Gregor. “He’s one of them,” they shouted. “He’s one of Mendel’s dwarfs!”

I’m not, of course. Mendel’s dwarfs were recessive. I am dominant. But at that time I didn’t know anything very much, except evasive glances and a brisk smile on my mother’s face and a cheerful but unconvincing assertion that what matters is what you are like inside. It’s easy to say that. All’s for the best in the best of all possible worlds. At home I had small chairs and a small bed and low bookshelves. The books were the normal size.

“Mendel’s dwarf,” they cried after me in the playground. “Mendel, Mendel.” The name became a taunt, a chant of loathing. I retreated to the bike sheds, but they confronted me there, their knees hovering in my line of sight, their feet stamping at me as though I were something to be trodden into the dirt, a cockroach perhaps. “Mendel, Mendel, Mendel’s dwarf!” they called, and the feet came through the bike racks at me until a

couple of older girls came in. “Leave off him,” they said carelessly. “What’s he done to you, poor sod?”

“He’s Mendel’s dwarf.”

“Oh, piss off.”

The boys went, chastened by age and sex. The girls eyed me with distaste through the bike racks. One of them seemed about to say something. Then she shrugged as though the effort didn’t seem worthwhile. “Come on,” she said to the other. “Give us a fag.”

I left them lighting up their Woodbines and scratching themselves.

“It’s a problem you have to live with,” the headmaster advised me. I told him I’d not realized that before, and thanked him very much for sharing his insight with me. He answered that being insolent wouldn’t help. Or being arrogant. I asked him whether being submissive might. Or being recessive. He told me to get out of his study.

A problem you have to live with

. That’s a good one, isn’t it? It isn’t something I

live with

, as I might live with a birthmark or a stammer, or flat feet. It is not an

addition

, like a mole on my face, nor a

subtraction

, like premature baldness: it

is me

. There is no other.

The curious thing is that I am doubly cursed. I am like I am, and yet I want to live. That’s another character, a more subtle one than dwarfism, but an animal character nevertheless, possessed by almost every human being. The Blessed Sigmund Fraud was wrong. There is no death wish, no

Todeswunch

. If there were, no animal species would survive, and certainly not our own damned one. But if there were a death wish, things would have been a lot easier for me: head in the oven, overdose of pills, fourth-floor window, the possibilities are endless. In the

underground I’ve often stood on the edge of the platform as the train came in, and thought about it. But no, you’ve got to live with it. You aren’t actually given the choice. No one is. I use the second person to include the whole of the human race. No one is exempt. You are all victims of whatever selection of genes is doled out at that absurd and apparently insignificant moment when a wriggling sperm shoulders aside its rivals and penetrates an egg. “What have we got here?” Mother Nature wonders. “What combination have

we

thrown up this time?” It’s like checking over the results of some lottery, the numbers drawn every day, every minute of

every

day; and every time someone a winner and someone a loser. No need to say which I was.

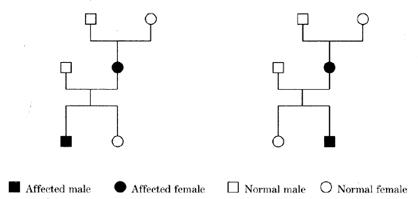

Two genealogies from dwarf studies, discovered in a book of medical genetics that I found one day in the public library. The diagrams have a pleasing sense of design about them, don’t they? There is a balance, a rhythm, a subtle asymmetry that halts the eye. The whole has something of the composition of a Mondrian painting, or perhaps a doodle by Miró: