Mendel's Dwarf (41 page)

They elected him abbot in 1868.

This shall not prevent me

, he wrote to Nägeli,

from continuing the hybridization experiments of which I have become so fond; I even hope to be able to devote more time and attention to them once I have become familiar with my new position

.

It was, of course, an illusion. Although he gave up his teaching, as abbot, he found less and less time to devote to the experimental garden.

Despite my best intentions I was unable to keep my promise given last spring. The

Hieracia

have withered again without my having been able to give them more than a few hurried visits

…

4

That was it, really. The excitement and optimism of youth gave way to the dullness of middle age. His scientific interests degenerated into mere stamp collecting—beekeeping and meteorology—while his innate stubbornness found an outlet in a bitter and pointless dispute with the fiscal authorities over tax demands on the convent. A stream of letters to the taxman issued from his pen. He argued, he debated, he looked for loopholes, he looked for escape clauses; he never gave ground.

He retreated within his carapace.

My time will come

, he said. He took his temperature readings and his rainfall readings, he grafted fruit trees and cultivated flowers, he smoked, he coughed and wheezed, he heard the pounding of his heart in his ears, he felt the gross oedemic swellings of his legs, and he never let anyone

but his two nephews past the barricades of isolation. They were medical students, the sons of Theresia, being supported at the medical school in Vienna by their uncle. Thus was Theresia’s generosity as a little girl paid back.

“They want to put me away,” he told them.

You may imagine their condescending smiles at Uncle Gregor’s suspicions. “Who, Uncle? Who wants to put you away?”

“The brothers. They want to get me declared insane and sent to a lunatic asylum. They want to pay their damned tax and get on with living their tiny little lives. You know that the bishop has set them to spy on me? You know that? They all want me to surrender. But I won’t. Oh no. Look, let me show you this …” And another of the letters would be produced, the page closely inscribed in his careful copperplate hand, full of the twists and turns, the repetitions and reiterations of a mind obsessed.

But a spark still glowed among the ashes of genius. There is the

Notizblatt

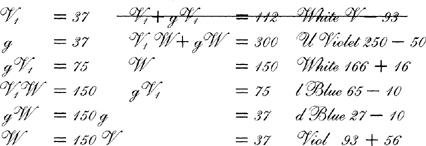

, a fragment discovered in the library of the monastery long after Mendel’s death. It is a page of jottings written in his careful copperplate hand on the back of the draft of a letter dealing with monastery business of 1875:

It goes on down the page. He is still playing around with numbers and ratios, trying to fit experimental results with expected values, trying to nose out further applications of the laws he had discovered. There is the odd correction, the occasional scribble, but as you read it you can feel him thinking, as

palpably as if he were sitting there before you at his wide desk in the prelate’s quarters, with his glasses propped up on his high forehead and his face set with concentration. It is like watching the dying of a brain, the last firings of the last neurons, the last breath of life.

1

. See “Progress in the study of Achondroplasia,”

Trends in Genetics

11, May 1995.

2

.

http://www.cornell.edu

3

.

http://www.fi.muni.cz/masaryk

4

. Final letter to Nägeli, 18 November 1873.

T

he simultaneity of events. A bright afternoon in

Mitteleuropa

, with the sun slanting on the fields and forests of Moravia and glittering on the concrete and glass of Brno’s suburbs as a coach brings travelers back from the north; a dull day of drizzle in the offshore western island, with rain glistening on the tarmac and running in shimmering rivulets down the windows of the Hewison Fertility Clinic. The two worlds coincide, come together contingently if not spatially, as the phone rings in the reception of the hotel in Brno at the exact moment that passengers troop in from the car park outside.

A distant, almost apologetic voice: “Ben? It’s me.”

What does one say? What does one say that has not been said already so many times that the words have lost their savor? Thus it is merely, and bathetically, hello.

“The pains have begun. The doctor warned me that it’ll still be quite a long time … Anyway, I just thought I’d let you know.”

Then the receiver is returned to its cradle and the worlds separate again like fragments flung apart by a silent and irremediable explosion: the coach passengers are queuing for the lift to take them up to their rooms (only one lift is working, and that can manage only three people at a time); and Jean is replacing

the receiver, closing her eyes, breathing deeply and steadily as she has been taught.

Her husband was with her for some of the evening. “Get some sleep,” she told him. “Nothing’s going to happen for hours.” He went home with a display of reluctance. She had a disturbed night, drifting in and out of sleep, jerked to wakefulness by spasms of pain, allowed to doze back to unconsciousness until the next assault. Occasionally a nurse looked in to see how things were going, smiling in that crisp and distracted manner nurses have.

“All ready for the battle, Ben?” Gravenstein asked as we sat down to breakfast next morning. She surveyed the food with dismay. “Christ, how do these Czechs keep

any

control over their weight?”

It was another day of sun in central Europe. The dining room was dissected by shafts of light. They cut across the groups at breakfast, spotlighted their shifting alliances and friendships, highlighted their promiscuity of mind and body. “You see that guy from Stanford, and the woman from Manchester?” Gravenstein said confidentially. “Well, they came down in the elevator at

exactly the same time

. How about that? That is the

third day

running that it’s happened. And I know for a

fact

that she has a husband and two children back home.” The woman was blushing at something the Stanford man had said, blushing and looking round as though to spot eavesdroppers. Gravenstein caught her eye and smiled conspiratorially across the room at her.

After breakfast I made a call to London. An anonymous voice

told me that she was sure all was going well, but no, I couldn’t speak with Mrs. Miller. Mrs. Miller was in labor.

It was drizzling and gray when Hugo arrived at the clinic that morning. An anemic half-light flooded the city with vague and unsubstantiated promises of better things to come. Jean lay there in the labor room looking old and drawn, her face slick with sweat. She lay in a plain white gown, with a fetal cardiac monitor attached to her swollen belly. A nurse turned a knob on the machine so that Hugo could hear the strange rippling sound of the baby’s heart, like horses galloping toward the scene of some unknown battle far in the electronic distance.

“There it is,” said the nurse proudly, as though the child had something to do with her. “What a tough little thing.”

“You look exhausted,” Hugo said to his wife, and Jean smiled at him and achieved that trick women have, to comfort the expectant father when it is the mother herself who should be comforted. “I’ll be all right,” she told him, as though she had a say in the matter. “A bit tired, but I’ll be all right.”

Coincidence. The simultaneity of events. Jean lies on a bed in the Hewison Fertility Clinic while I mount the podium of a lecture theater at the Masaryk University of Brno, watched by the worthies of the university, by the officials of the Mendelian Association of America, by representatives of Hewison Pharmaceuticals, by members of the Mendel Symposium. Jean brings comfort, while I trade in discomfort:

“One hundred thirty years ago, in a school building not far from here, a quiet, introverted, stubborn friar gave a lecture on the breeding of peas. With that lecture he lit a fuse, a fuse

that burned unnoticed for thirty-five years until the very opening of this century, when the bomb exploded. The explosion is going on still. It engulfed me from the moment of my conception …”