Metallica: This Monster Lives (49 page)

Read Metallica: This Monster Lives Online

Authors: Joe Berlinger,Greg Milner

Tags: #Music, #Genres & Styles, #Rock

I was sitting there, wondering what to do, feeling the Dude’s glare on me, when I remembered that I hadn’t called Lars to give him his daily progress report. He didn’t know about the New Line dilemma. I went upstairs and managed to reach him on his cell in Australia. It was already the next afternoon there, and he was just getting out of bed. I cut to the chase. “We’ve generated a lot of interest, and New Line is offering us $4.3 million, the full cost of the film.”

UNLEASHING THE MONSTER

Some Kind of Monster

opened in New York on Friday, July 9, 2004. Late that afternoon, Bruce and I walked from our office in the West Village to the Landmark Sunshine Cinema on the Lower East Side. As we passed the marquees of some downtown screens, I marveled at how many documentaries currently had theatrical releases:

Fahrenheit 9/11, Super Size Me, Riding Giants, Control Room, Imelda, The Corporation, America’s Heart and Soul, The Hunting of the President.

This really is the golden age of documentaries in the cinema. In 1992, the year

Brother’s Keeper

opened, only five documentaries were released, with generally anemic box-office results. During the first half of 2004, forty-four documentaries were released theatrically.

Fahrenheit 9/11

and, to a lesser extent,

Super Size Me

, even set box-office records.

When we got to the Sunshine, we discovered that there were midnight screenings of

This Is Spinal Tap

scheduled for that weekend. This was ironic, because several critics had made a connection between

Monster

and

Spinal Tap

, a comparison I found facile at best and inaccurate at worst. But it was funny to see the two movies on the same marquee. In

Spinal Tap

, the band is annoyed to find itself listed after a puppet show on a marquee (“It’s supposed to be

SPINAL

TAP

AND

PUPPET

SHOW

!”), and there was

Spinal Tap

, listed underneath

Some Kind of Monster

at the Sunshine. All four of that night’s

Monster

screenings sold out, while

Spinal Tap

played to about 20-percent capacity. Although the box office eventually softened,

Monster

had the highest per-screen average in America its opening weekend.

“Really?” He sounded more than just groggy. I could also hear a quizzical tone in his voice that suggested he was a little disappointed, since he’d really warmed to the idea of releasing

Monster

ourselves.

5

“The thing is, they’re insisting that we take out twenty minutes.”

“Well, do you guys want to do that?”

“You know, Lars, we really don’t. Five minutes could go for sure, ten minutes tops, but twenty minutes would really hurt the film.”

Lars didn’t hesitate. “Look, it’s not about the money, it never has been. It’s about what people will think of this movie in five years, in ten years. We want to make the best film possible.”

And I believe that’s what we did. If you sit down to watch

Some Kind of Monster

, make sure you’ve got 140 minutes to spare.

On the last night the Q Prime managers were in town, we all went to Grappa, my favorite restaurant in Park City, for a celebratory dinner. Afterward, as my wife and I walked down on Main Street, Cliff came up beside us. Loren asked him what he thought the future held for

Some Kind of Monster.

He pondered the question for a moment. “Forget the PR value of the film,” he said, perhaps remembering that PR was the sole reason he’d asked Bruce and me to turn on our cameras in the first place. “Forget whether it helps Metallica sell albums. The real value of this film is that, in five years, if those guys fall back into their old patterns and habits …” He looked at me and smiled. “I’m gonna sit them down and make them watch it all over again!”

CHAPTER 23

LIVING THE MONSTER

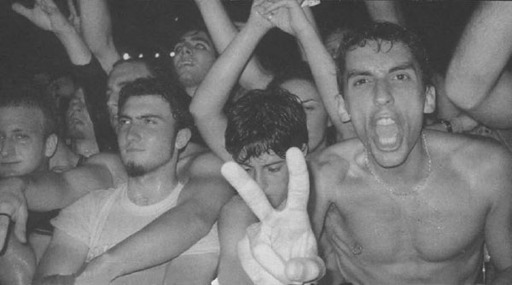

Some of the crazed fans at the Imola Jammin Festival (Courtesy of Joe Berlinger)

05/20/02

INT. KITCHEN, HQ RECORDING STUDIO, SAN RAFAEL, CA - DAY

BOB

: Well, you know, going back to [what Phil said] : Tap the energy. It’s not like, “Okay, we had this argument, now let’s go beat on our instruments.” I don’t think it’s as simple as that, but I do think there is something you can tap into here, lyrically. … There is still a lot of anger. I just saw it in this room. There is still a lot of isolation, there is still a lot of hate, there is still a lot of not understanding. This is the kind of stuff that has to be talked about. This is what great writers and great musicians do. They relate to that stuff, so other people can know they’re not alone.

JAMES: (to Joe) :

Or you can just film it so we don’t have to write it. (laughs)

Some Kind of Monster

began life as a promo video about a band trying to make a record. It quickly became a movie about a rock band trying not to fall apart. Somewhere along the way it also became something more, at least for those of us who lived it.

One reason that

Monster

feels so authentic—at least to me—is that the journey of making it was completely unplanned. The process affected us deeply because it was largely out of our control. In this age of reality TV, every aspect of human experience has been poked and prodded in the most contrived, preconceived ways. But with

Monster

, we all took what life dished out for us and learned to live with it. If we had sat down with Metallica in 1999 and told them we wanted to make a film that turned inside out the glorified image of the rock hero by revealing these guys’ individual insecurities, and that hopefully they’d all learn something about themselves, that door to the Four Seasons penthouse suite really

would

have hit our asses on the way out. Aside from a desire to make a personal film, we had no preconceived notion of what

Some Kind of Monster

would become. We all just let go of the steering wheel and went along for an incredible ride. And yeah, the car did crash. But it wound up being a happy accident.

The allure of happy accidents is one reason I’ll never stop making verité films, no matter how much I continue to work in fiction film and television. Cinema verité is an art form that, at its best, provides the emotional catharsis of a good storytelling experience while imparting real, tangible information that makes us see our world differently. Another reason I’ll never turn my back on my first love is because of the life lessons these films provide for me.

Brother’s Keeper gave

me the courage to be a filmmaker and taught me to accept people for their humanity.

Paradise Lost

made me examine my views on the death penalty and the fallibility of the justice system. But

Monster

is the film that’s helped me grow the most. When we started filming at the Presidio, I was a broken man. By the time we loaded our gear out of HQ, I had a new perspective on the creative process that allowed me to tame my ego, accept my weaknesses, and make sense of my failures—gifts that will have a profound impact on my life as a filmmaker, father, husband, collaborator, and friend. I learned all this from a group of guys who, as far as most of the suburban parents that I hang

out with during my daughter’s Saturday soccer games are concerned, are incapable of uttering a coherent sentence, let alone imparting such life lessons.

For me, the crowning moment of making

Some Kind of Monster

, the moment I realized how much making this film has meant to me, came during the summer of ’03, on the Summer Sanitarium tour. We were busy editing

Monster

, but we took the time to film various tour stops throughout the summer, beginning with some European dates. After two years, we’d become accustomed to having such an intimate and informal relationship with Metallica that it was a little jarring to find ourselves having to prove ourselves to the road crew, who had no idea that we had just filmed these guys for the past two yeans in the most intimate of situations. To them, we were just another video crew with the potential to complicate their jobs. It took the crew a few dates to figure out that we had a special relationship with the band that had allowed us unprecedented access.

Much of the concert footage at the end of

Monster

was shot about an hour outside of Italian city of Bologna, at the Imola Jammin Festival. After traveling with the tour for several weeks, this was our last date before returning to the editing room in New York. At every show, I had been trying to shoot some intimate backstage footage of James, just before he hit the stage. I wanted to capture his preshow rituals, so that we’d see him reclaiming his former status as a rock god after two years of battling the excesses of stage life. My plan was for our camera crew to ride with James in the little van that took him from the heart of the VIP area to the backstage entrance, and then have the camera follow him up onto the wings of the stage. Each time I’d asked, the crew had turned me down, citing security reasons. In Bologna, I decided to bypass the tour’s production staff and ask James’s bodyguard, Gio, to relay the request directly to him. Instead of sending in our DP Bob Richman with his bulky DSR-500 camera and a separate soundman, I offered to ride with James alone and shoot the whole thing with my small PD-150, using the camera’s onboard microphone and a little camera-mounted miniature light. I wasn’t even sure I would be able to cover the situation sufficiently with this camera, since it’s not designed for low-light situations; the sound might also be a problem. But I felt I had to take the risk if we were going to get this shot at all. I promised I would stay out of James’s way

A few minutes before showtime, Gio told me James had given his assent. As James was coming out, I jumped inside the vehicle, a sleek Mercedes van. I had been asked to sit in the back row of the van, instead of my requested camera position in the front passenger seat. I was concerned that all I would get is the back of James’s head. As he positioned himself into the middle row of the

van, he turned around to see who else was there. For a second, I thought he was turning around to give me a “what the fuck?” glance that would result in me getting thrown out, but he was just drawn to the camera’s light, which illuminated the van’s interior. The next guy to step into the van was Phil Towle. I did a double take: what was

he

doing in here? Phil had agreed to travel with the band members for the first few weeks of the tour, to help them ease back into their role as the world’s biggest rock-and-roll band, but I didn’t think he’d actually follow them to the stage in the van. Phil stepped on my foot and knocked my camera as he climbed over me. I twisted in my seat to make room for him. James watched Phil take his seat, which actually gave me a better shot of James. Given the complicated relationship between Metallica, Phil, and Berlinger-Sinofsky over the previous two years, it seemed suitably metaphorical that Phil’s presence made the shot I wanted harder to achieve but ultimately better than what I’d planned. Last into the van was Rob Trujillo and James’s bodyguard. My camera was knocked yet again.

We drove alongside the barricades that separated the crowd from the backstage entrance. I got a few quick shots of each of the band members as they exited their vehicles and then followed James on foot as he walked to the wings of the stage and greeted the crew. I kept bracing myself to be pulled back at any moment by the crew, since none of them had been told that I was allowed to follow James. I walked to the edge of the stage, where I could see the massive crowd. Now I was really pushing it, since a cardinal rule of Metallica on the road is that anyone backstage in a position visible to the audience must wear a black T-shit, which I lacked. More than 100,000 fans had waited all day in 105-degree heat to see Metallica, the last of six bands. The air had cooled slightly, but not much. The sun was setting, giving the open sky the beautiful hue of the “magic hour.” When we reached the stage, a synthesizer hum rose from the speakers and the crowd began to roar. The fans went wild and began to sing along as the sound system played “Ecstasy of Gold,” Ennio Morricone’s wordless tune from

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

, which Metallica fans worldwide know is the last thing they’ll hear before their heroes take the stage. This was the most pumped audience I’d seen on the tour—or in my life, for that matter. I had never before felt an energy like this.